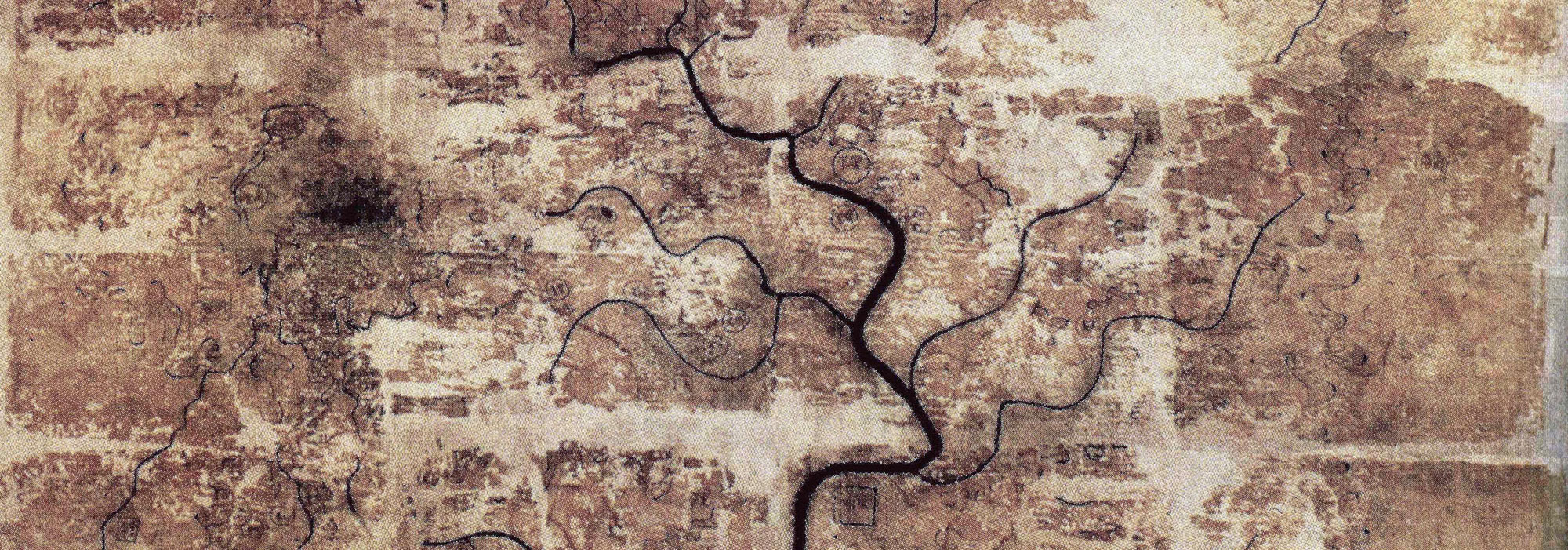

In 168 B.C., a lacquer box containing three maps drawn on silk was placed in the tomb of a Han Dynasty general at the site of Mawangdui in southeastern China’s Hunan Province. The general was most likely the son of Li Cang, the ruler of the Changsha Kingdom—a fiefdom of the Han Empire—whose own well-appointed tomb lay nearby.

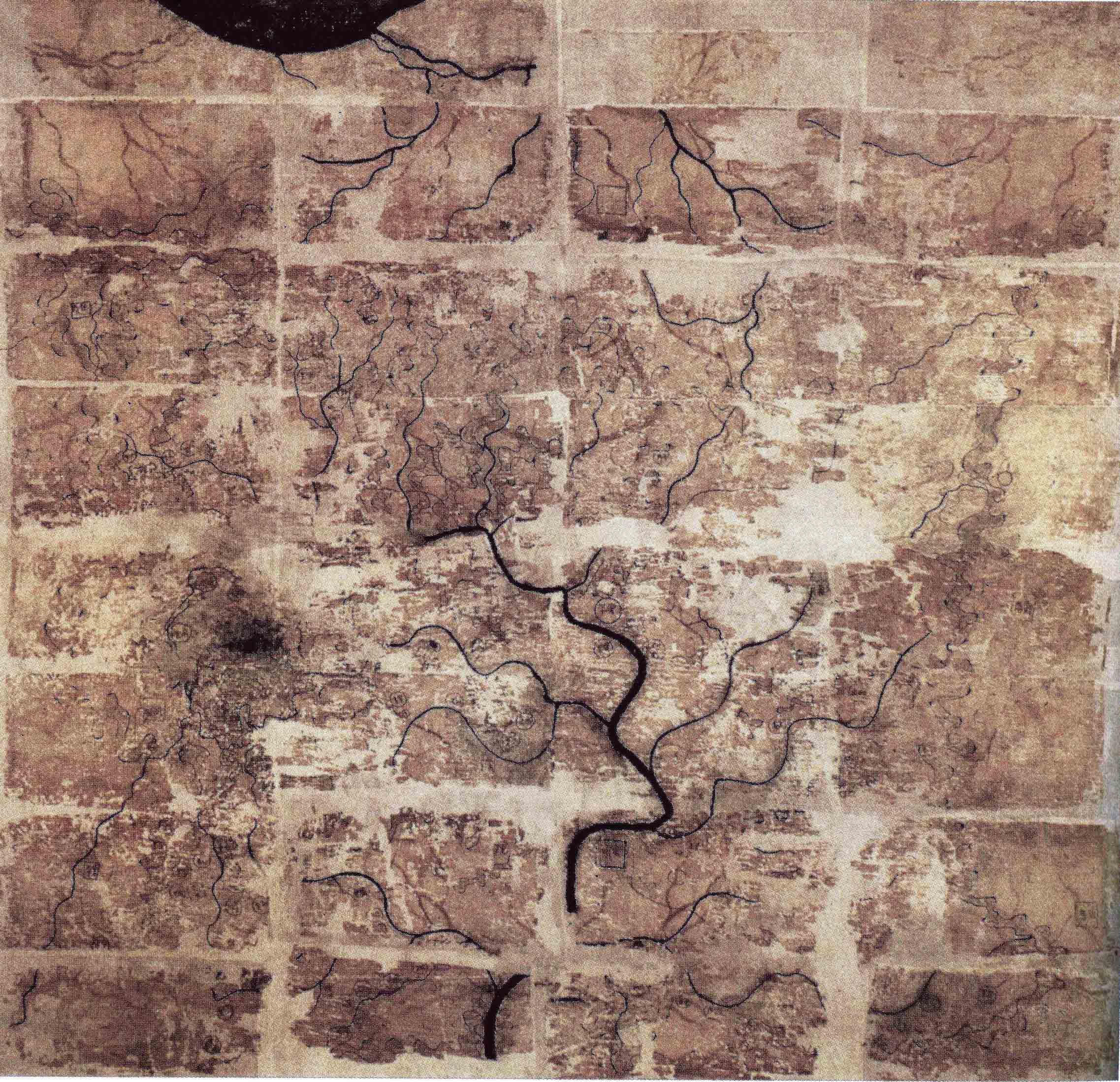

Each map presents a section of the Changsha Kingdom. One map, now largely in tatters and difficult to read, seems to show a city or mausoleum. Another focuses on the locations of military garrisons in a region that lay near Changsha’s frontier with a fractious neighboring kingdom. The third map, shown here, illustrates the mountains, rivers, and important settlements of the southern half of Changsha.

The Mawangdui maps demonstrate a high degree of standardization, especially in their use of abstract signs, such as squares to symbolize cities, says Cordell Yee, a cartographic historian at St. John’s College in Annapolis. He points out that the maps are so sophisticated that they were likely produced according to long-established cartographic traditions. “This suggests mapmaking was already well developed in China by this time,” says Yee. The maps were undoubtedly indispensable for administrative and military planning purposes, but they may also have been enjoyed as works of art. Next to depictions of a prominent mountain range, the Jiuyi Shan, or Nine Beguiling Mountains, the dark area at the far left, the mapmaker carefully drew in shadowy images that may depict the reflection of the peaks in a nearby lake.