In the mid-nineteenth century, Ireland was in the midst of a crisis. The repeated failure of the potato crop had driven millions of people to the brink of starvation. This catastrophe, combined with the simmering social, religious, and political tensions associated with British rule in Ireland, forced thousands of people to flee the country each month. Many of them left from the small town of Cobh, in Cork Harbor. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as many as 2.5 million Irish men, women, and children departed from Cobh alone, more than from any other port in Ireland. Tearful families gathered on the waterfront to say their goodbyes. Many were seeing their loved ones and their homeland for the last time.

As they sailed out through Cork Harbor, they passed a foreboding island on their right featuring a bleak stone fortress that must have struck a jarring contrast to the colorful rows of Victorian architecture that lined the streets of the town they had just left behind. The island was known all over Ireland, and everyone who sailed past it must have shuddered. It was Spike Island, the site of Ireland’s most notorious prison.

Located along Ireland’s southern coast, Cork Harbor is perpetually bustling with activity. Pleasure yachts, cruise ships, tour boats, even Irish naval vessels, crisscross its waters. At its northern end lies the mouth of the River Lee, and farther inland, Cork, the Republic of Ireland’s second-largest city. In the early twentieth century, the harbor’s scenic town of Cobh gained some notoriety for its link with two famous maritime disasters—it was the last port of call for Titanic in 1912 and, three years later, Lusitania was torpedoed just off its shores. Memorials to both tragedies stand close to its waterfront.

Today, Cobh is perhaps best known as the place to catch the ferry to Spike Island, which is one of Ireland’s most popular tourist attractions. Once the site of the largest prison in the British Empire, Spike Island was described by those held there as hell upon earth. Early on, it was a place synonymous with death—more than 1,000 prisoners perished in its first seven years of operation. The British, who controlled Ireland until 1921, conceived of the prison as a solution to what authorities saw as the increasing criminality of the Irish people. While Spike Island did house hardened criminals and political prisoners—most famously Irish nationalist John Mitchel, for whom the fort that became the prison is now named—many confined there were petty thieves who had fallen on hard times and committed small crimes to make ends meet. In the 1840s, even minor offenses could get someone sent to Spike Island. As the years wore on, some inmates were sent to Australia, some returned to their homes in Ireland, but many never made it off the island.

The 104-acre island was under the ownership of the British and, later, the Irish military from the late eighteenth century until 2011, when it was transferred to the civilian Cork County Council. This provided the opportunity for archaeologists to explore Spike Island for the first time. University College Cork bioarchaeologist Barra O’Donnabhain began a project in 2013 that included not only excavations at various sites across the island, but also a deep dive into government archives, firsthand accounts of prisoners, officials, and guards, and other historical sources. Over the past six years, O’Donnabhain and his team have helped untangle some of the site’s history and gained new insight into how the nineteenth-century British penal system in Ireland functioned. Along the way, they have uncovered evidence of Spike Island’s operational deficiencies, deplorable living conditions, and institutional racism. They have also revealed the respectful behavior some prisoners exhibited toward their fellow inmates upon their deaths.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the British constructed a series of fortifications on the strategically located Spike Island. Its location opposite the narrow mouth of Cork Harbor ensured that any ship entering or exiting had to sail past its guns. The first fort was built during the American War of Independence as a defense against a potential American attack. A second network was erected during the French Revolution, and a third, much more substantial fort, known as Fort Mitchel, was begun in 1804 after the rise of Napoleon. This star-shaped complex contained massive bastions, ramparts, and a moat, but was only partially completed when work was halted in 1820. It would not be fully completed until decades later, built by the very inmates incarcerated behind its walls.

Around this same time, the British penal system was beginning to evolve. Prior to the nineteenth century, lawbreakers were incarcerated for brief periods of time in small local holding cells. The concept of larger, permanent prisons was unknown in the British Isles, but that was soon to change. “Ireland had no purpose-built prisons in 1800, but, by 1830, every single county had a jail, and all the big towns had a city jail,” says O’Donnabhain. He believes that the events of the French Revolution, which unsettled the British upper classes, may have had a direct impact on this movement. “It’s the fear of the poor, the fear of revolution that does this,” he says. “It’s like they said, ‘We have to make sure that this doesn’t happen here. How do we do that? We lock them up.’”

Another way the British prevented popular unrest was to simply dispose of the poor and criminal classes by shipping them out of the country. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, one of the fundamental tenets of the British penal system was transportation. Under this system, people convicted of felony offenses were involuntarily exiled to distant colonies across the British Empire. It was common for an Irishman or Irishwoman to be sentenced to seven years transportation to Australia, whereby they were deported from Ireland and pressed into penal servitude. When they had completed their sentence, they were freed, but they were not allowed to return home. For the British, this process achieved two objectives: It rid society of people they considered undesirable, and, at the same time, supplied their colonies with a much-needed labor force. “What they were doing was harvesting the poor and sending them away,” says O’Donnabhain. “It was social engineering. They were looking for a working class for Australia.”

Spike Island played a major role in the British penal system in Ireland—but it was only supposed to be a temporary solution to a developing crisis. By the mid-nineteenth century, the British government was running out of places to send Irish convicts. Since the 1780s, they had been sent to Australia, but colonial authorities there were growing wary of the practice and began to resist. As it took longer and longer to find suitable places to send Irish criminals, Irish jails became exceedingly crowded and increasingly dangerous.

Another factor contributing to perilous overcrowding was the Great Famine, which lasted from 1845 to 1852. This catastrophe caused the deaths of up to one million people, but millions of others were driven to wander the countryside in search of food. Many of them resorted to crime in order to survive, stealing food, animals, or small items to trade or sell. Those who were found guilty of felony grand larceny were commonly sentenced to transportation. But many British statutes had not been updated in centuries, and the definition of felony grand larceny had not changed since the thirteenth century. It was still defined as the theft of any property valued over one shilling, even after centuries of inflation. This meant that stealing even the smallest of items was punishable by transportation. Not only had it become more difficult to ship Irish criminals away, but the number of them was also growing exponentially. To alleviate the stress affecting Ireland’s jails, the British government looked to the island in the middle of Cork Harbor.

Spike Island’s size, its location, and its fort infrastructure convinced government officials that it would make an ideal depot where criminals could be held temporarily as transport ships were prepared. However, by 1853, transportation of small-time offenders was abolished and most Irish convicts began serving their sentences at home. This meant that Spike Island ended up housing prisoners longer than was originally intended. O’Donnabhain’s recent research and excavations have shown that it was drastically unsuitable for this endeavor. Spike Island was never intended to hold more than a few hundred convicts for a short amount of time, but it remained open as a prison for 36 years, and at its height had a population of around 2,500 inmates.

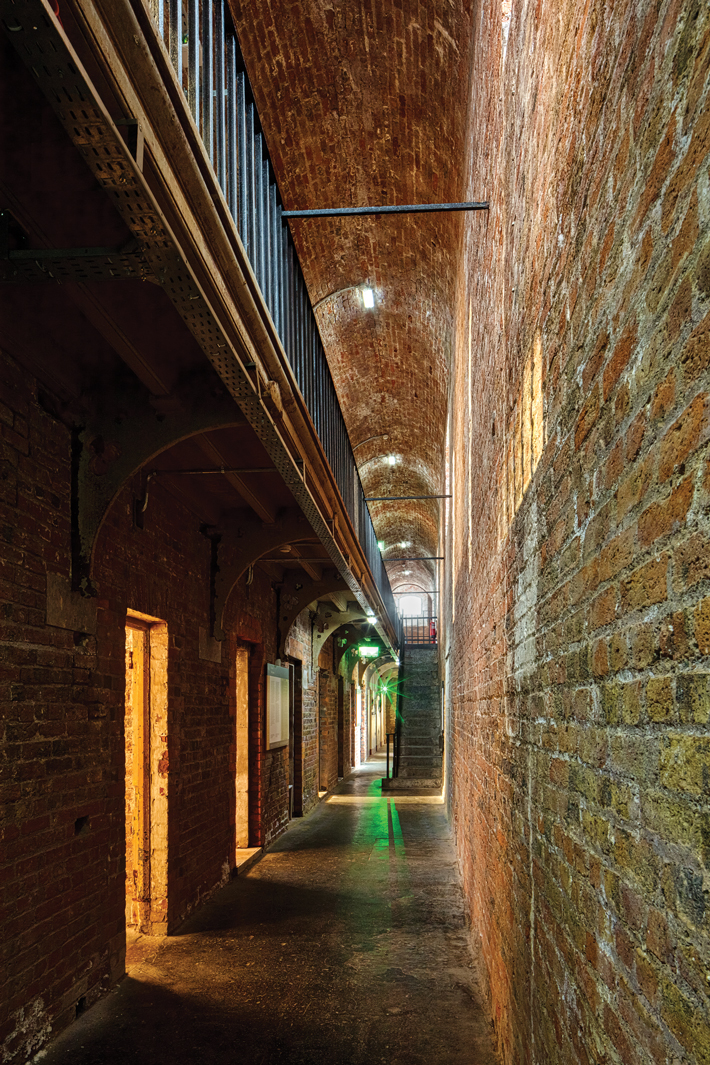

One of the major challenges, at first, was that there simply was not enough room for the number of convicts being sent there. “They immediately just jammed the place full of people,” says O’Donnabhain. The fort’s former military barracks were transformed into convict housing. Each room, which measured 48 feet long by 18 feet wide, had originally been intended to house around 13 British soldiers. Yet as many as 50 Irish prisoners were assigned to each of these quarters, almost four times the anticipated capacity.

Excavations have revealed why convicts frequently complained about Spike Island’s notoriously bad drinking water. While digging beneath the outdoor prison yard, O’Donnabhain’s team uncovered pipes from Spike Island’s overtaxed and inadequate sewer and freshwater systems. What they discovered was that, in fact, the two were occasionally one and the same. “We found that they were harvesting rainwater from the roofs of all the buildings and funneling it into a tank underneath the yard,” he says. “Fresh water is going one way, sewer pipes are going another way, and they would have gotten mixed quite regularly. Conditions were grim.”

Despite the draconian conditions, the men were able to occasionally break the monotony of prison life. During the recent excavations, dozens of small objects were found hidden beneath cell floorboards, stowed there safely out of the sight of prison guards. There were carved pieces of bone and stone, some of which were made into gaming pieces such as dominoes, while others were just small objects of prisoner art. These objects represent small acts of resistance to prisoners’ highly regimented lives.

While no women were sent to Spike Island, children as young as 13 were held there, 200 of whom were housed in a windowless bunker-like building that had once been used as the fort’s gunpowder store. Prison records indicate that most of the youths were sentenced to Spike Island for stealing items as trivial as umbrellas, handkerchiefs, or shoes. Some were sent there simply because they were homeless, as vagrancy had been criminalized. According to O’Donnabhain, the criminal justice system of the time was purposely stacked against the young. “They were really harvesting these kids for the colonies,” he says. “They were looking for young, fit men and women. They’re not going to bother transporting a 50-year-old; it’s a waste of time and money. But teenagers—they were prime for the picking.”

Life on Spike Island was, not unexpectedly, hard, as convicts were forced to work long hours on various government building projects around Cork Harbor. To help ensure the men’s best behavior, each inmate’s conduct was recorded on a badge that they were forced to wear on their sleeve. Prisoners who misbehaved were treated harshly. Originally, there was a series of 11 punishment cells. These were actually old soldiers’ latrines resembling outhouses that were converted into isolation booths. After a prison guard was murdered in 1856, a new punishment block was constructed. Its cells were dark, cold, and known to drive some men to insanity. “It’s all about sensory deprivation,” says O’Donnabhain. “You were literally in the dark.”

Spike Island’s harsh conditions, poor medical care, and overcrowding led to an almost astronomical death rate, especially in the years during the famine when the prison first opened. The first prison ship docked at the island in October 1847 carrying 109 men. By the end of the year, two months later, seven of them were dead. That trend would get worse before it got better. Around 1,200 men and boys died on Spike Island throughout its three and a half decades as a prison. In its most deadly year, almost one prisoner was buried each day. The overwhelming majority of deaths occurred in the first seven years, when conditions within the prison were at their worst. “They weren’t trying to kill them,” says O’Donnabhain, “there were just way too many people there.” It was not until penal reforms in the 1850s reduced Spike Island’s prisoner population from 2,500 to 900 that the numbers of dead finally began to drop.

The main cause of prisoner death was disease, especially tuberculosis. Records kept by prison officials blame Spike Island’s cold, windy climate for the spread of the disease. But officials also expressed the opinion that there was not much they could do since the Irish were constitutionally vulnerable to disease—a notion at which O’Donnabhain balks. “There is a whole aspect of race that permeates throughout this place,” he says. “The Irish are not particularly susceptible to tuberculosis—people who are malnourished and living in overcrowded conditions are.”

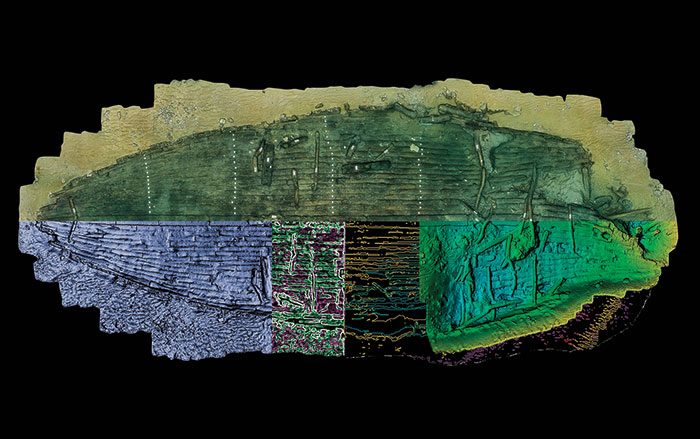

Over the past few years the project has investigated one of Spike Island’s two known cemeteries. Records show that the famine-era cemetery, which contained around 1,000 inmates, was located on the east side of the island. It was subsequently buried beneath 20 feet of debris during landfilling to improve Spike Island’s defenses and has never been firmly located. With the help of old maps of Spike Island, O’Donnabhain and his team discovered a second graveyard, which opened around 1860, on the western side of the island. This provided them with the opportunity to examine some of the inmates’ physical remains and to evaluate how the dead were treated. “We wanted to see the impact that Spike Island had on the bodies,” says O’Donnabhain. “Historical records say that tuberculosis was the main cause of death, so we wanted to see if we could confirm that, and whether we could see any other processes.”

Chemical analysis of isotopes left behind in skeletal remains can identify certain information about a person’s diet. The men who were buried in the second Spike Island graveyard died in the 1860s and 1870s, but had grown up in Ireland during the Great Famine. Their life history of starvation was evident in their bones. Other tests showed that the poor diet provided to the inmates while on the island caused many of them to suffer from xerophthalmia, a condition triggered by vitamin A deficiency that can lead to night blindness and, in some cases, even total blindness.

One of the most surprising findings from the graveyard excavation was its high degree of organization and the level of care shown to each inmate’s burial. The small plot of land was laid out in uniform rows, similar to a military cemetery. On rare occasions, when an inmate died under unusual circumstances such as suicide, a carved headstone was provided. Each individual was also buried in a coffin, which the team did not expect. “That really surprised us,” says O’Donnabhain.

Researchers discovered something even more surprising when they analyzed the coffins in the lab—they noticed that they were made from a different material than the team had originally thought. While the coffins were actually constructed from cheap wood, such as pine, they were painted to look as if they had been made from a more expensive material, such as oak. Thus, the dead would not appear to have been given a poor man’s burial, but, instead, something more dignified. This respectful gesture testifies to a sense of camaraderie among the convicts. “All of the grave digging and coffin building was done by other prisoners,” O’Donnabhain says. “It’s not being done by guards, so that was really an interesting result.”

However, the most peculiar discovery from the graveyard excavation was that around 10 percent of the exhumed skeletons were found to have parts of their skulls missing. O’Donnabhain suggests this may be evidence for autopsies that were carried out by Spike Island’s medical officers. But examination of the skull is at odds with normal autopsy procedures for a tuberculosis victim. Moreover, there is no evidence that the prisoners’ chest cavities were examined, as would have been normal for someone who died of the respiratory disease. Instead, O’Donnabhain believes that this highly unusual practice may have been associated with pseudoscientific theories of the time popularized by Italian physician Cesare Lombroso. These theories promoted the idea that certain individuals were naturally more prone to committing crimes than others, and that this “criminality” manifested itself in anomalies of the brain. “I’m tempted to link it to the idea of the natural-born criminal and that they wanted to see what is going on in the criminal mind,” O’Donnabhain says. “This biological notion of natural criminality hasn’t gone away, even today.”

The Spike Island prison finally shut its doors in 1883, at which time the island reverted to British military control. Overhauls to the British and Irish penal system had improved conditions, but, in the end, Spike Island’s ill-suited infrastructure and the exorbitant cost of running a prison on an island made it unfeasible to maintain. However, in 1985, after a 102-year hiatus, Irish authorities returned the island to its roots by once again installing a prison there. It was soon the scene of an internationally publicized riot and was eventually shuttered after two decades.

Although a visit to Spike Island today provides serene and picturesque views across Ireland’s greatest harbor, there is darkness beneath its beauty. America and Australia are known for their vast numbers of Irish immigrants. Some men and women went willingly, some did not. Whether they arrived at their destinations free or not, each eventually faced the difficult task of rebuilding their lives in a distant foreign country. All of them, though, had a chance to escape the bleak future that famine-era Ireland offered. The recent archaeological work on Spike Island has helped tell the story of those men and boys who were not able to make it out and provided a voice for those who still remain buried beneath its ground.