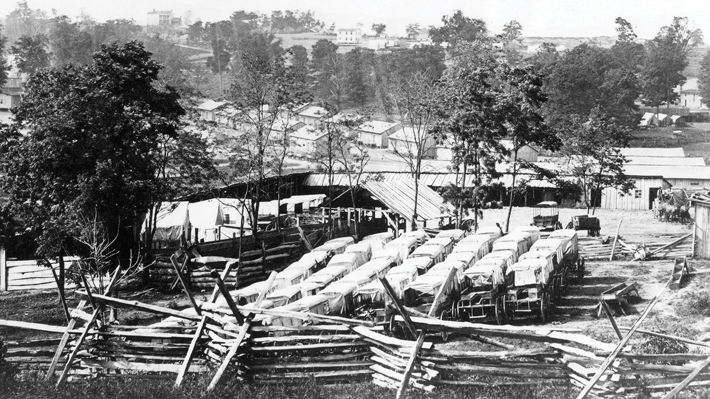

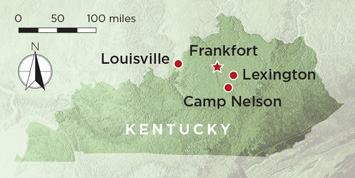

The only complete original building still standing at Camp Nelson in Jessamine County, Kentucky, is a sizeable house built around 1850 for the just-married Oliver Perry and his bride, the former Fannie Scott, whose family owned the land on which the house sits. It is now called simply the White House. But between 1863 and 1865, at the height of the Civil War, it was just one of more than 300 structures in the center of the camp’s 4,000 acres that housed all the required resources for an army at war. These included a supply depot, hospital, commissary, prison, ordnance storage facility, stables and corrals, a 50,000-gallon reservoir, woodworking shop, blacksmith shop, horseshoeing shop, harness shop, and a bakery that produced 10,000 rations of bread a day. There was also a hotel and tavern called the Owens House, a post office, and a few small eating establishments. Camp Nelson had been built to support the Union Army’s advance into Tennessee, and over its years of wartime service, tens of thousands of soldiers, both white and black, enlisted and were trained there. Camp Nelson was the largest of the eight U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) recruiting centers in Kentucky, and the third largest in the nation. All that remains aboveground, apart from the White House, though, are the remains of eight earthen and two stone forts, the earthen remains of a powder magazine, remnants of a few icehouses, and the stone foundations of two ovens.

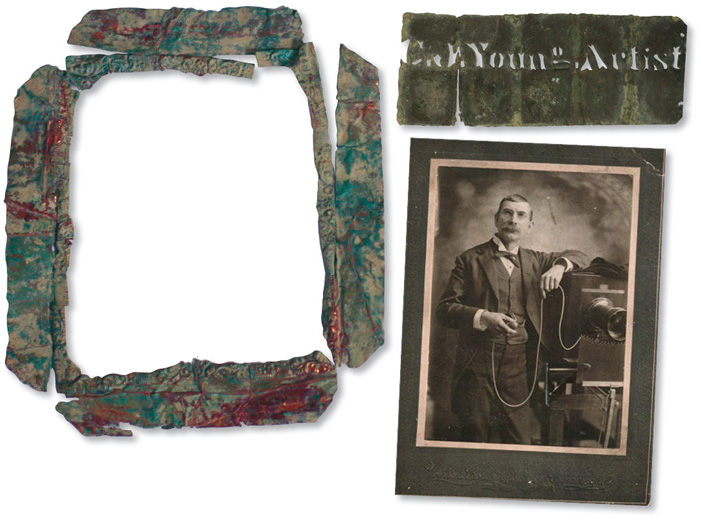

During recent excavations in an area known from nineteenth-century maps to have been the camp’s only licensed sutler’s establishment, a type of general store, Camp Nelson National Monument archaeologist Stephen McBride and a team from Transylvania University began to uncover picture frames, glass plates, mats, and glass bottles that originally contained chemicals used to develop photographs. They also found bottles embossed with the brand names “Bears Oil,” which had once held hair oil, and “Dr D Jayne,” which had once held hair dye. Soldiers used the dye to darken their hair for portraits, since light hair could appear white in the finished images, prematurely aging the subjects. In addition to these artifacts, the team also uncovered the remains of a small building—the first specialized photography studio ever found at a Civil War site. “The studio wasn’t documented on any extant maps of the camp, and Civil War photos were often taken in tents,” McBride says, “so finding something set up as a permanent photo studio was a real surprise.” The team recovered 10 metal stencils the photographer had used to sign his images and was therefore able to identify him as a man named C.J. Young. (See: “The Age of Pictures.”)

But Camp Nelson’s population consisted of more than photographers, merchants, carpenters, blacksmiths, bakers, and soldiers. Many black volunteers arrived with their families, creating a huge influx of refugee women and children. “Camp Nelson is one of the best preserved archaeological sites associated with USCT recruitment,” McBride says. “And it’s also one of the best places to explore the refugee experiences of African American slaves seeking freedom during the Civil War.” Through his work, McBride hopes to resurrect the too-often-lost stories of these women and children uprooted by the war that would determine their destiny.

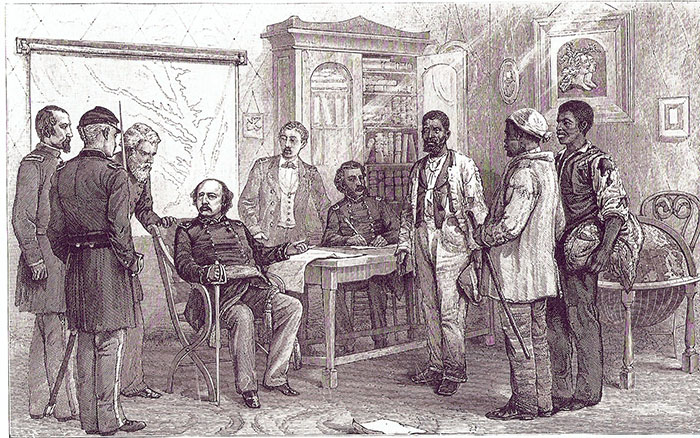

Black military enlistees in Kentucky were in a treacherous position. Kentucky did not secede from the Union, but slavery remained legal, and the state’s political leadership was vehemently opposed to the recruitment or enlistment of African Americans. They reasoned that a person could not be both a soldier and a slave. “The men could enlist with their owner’s permission,” McBride says, “but, as far as I know, not very many slave owners gave their permission.” A rare exception was that of Pvt. William Wright, whose owner, John Russell of Franklin County, allowed him to enlist. Russell received a signing bonus of $300. “Even without permission, black men came anyway, and they were rejected and exposed to violence both coming and going,” adds McBride.

On July 17, 1862, the U.S. Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, which authorized the president to seize all property belonging to the Confederate states, including enslaved people. On the same day, the Militia Act was passed, empowering the president to use former slaves in any military capacity “for which he deemed them competent.” The Emancipation Proclamation followed in September. “While originally President Abraham Lincoln’s singular stated goal for the war was to preserve the Union, he walked a tightrope when it came to slavery,” says historian Joseph Glatthaar of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “After the Proclamation, his goals shifted and he recognized the need to destroy the institution of slavery. This was the only way he saw to preserve the Union.” According to the Emancipation Proclamation, all enslaved people in the “rebellious states” were freed as of January 1, 1863. This allowed recruitment of black soldiers to begin in earnest. As Union forces advanced deeper into Confederate territory, more and more fugitive slaves volunteered for military duty. “These people escaped from slavery and liberated themselves because they heard of the arrival of the army close to them, and they hoped for safe haven and protection,” says historian James Downs of Connecticut College. “They left in a state of emergency, often under the cover of night, and made decisions in the middle of a major war.” By the end of the Civil War, 178,975 free and freed black men had served in the Union Army in 175 USCT regiments, constituting about onetenth of the army’s manpower. The USCT also included Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Asian Americans. An additional 19,000 African American men served in the U.S. Navy, and more than 37,000 black soldiers died for the Union cause.

Kentucky didn’t allow black men to enlist until 1864, and historian Ann Murrell Taylor of the University of Kentucky explains that it was the state where emancipation proceeded most slowly. “The traditional notion of Lincoln striking down slavery with his pen is a fantasy,” says Downs, “and slavery remained intact in Kentucky in any case, even after the war.” Nevertheless, by the end of the Civil War, 23 regiments of men of color had been formed there, totaling some 23,500 soldiers. In May 1864, after the army removed the requirement for owners to give their permission, 250 men enlisted in the USCT at Camp Nelson in just one day.

“I wanted to learn about the day-to-day lives of these men,” McBride says. “What possessions did they have that didn’t fit army regulations? What weapons did they use? What did they eat?” During the course of his excavations, McBride has located not only mess houses for civilian employees that were well known from contemporaneous maps, but also poorly documented USCT housing. This includes evidence of huts, streets that had become refuse-filled drainage ditches, and a few cellars, as well as objects from soldiers’ daily lives such as buttons; metal cups, plates, and pots; and some ceramic cups and plates as well. He has also found arms and ammunition that suggest the men used a wide variety of both up-to-date weapons and antiquated Model 1816 Springfield muskets.

EXPAND

The Age of Pictures

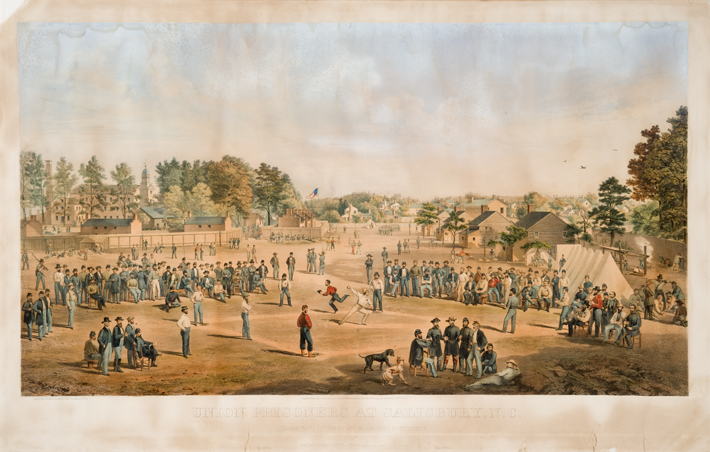

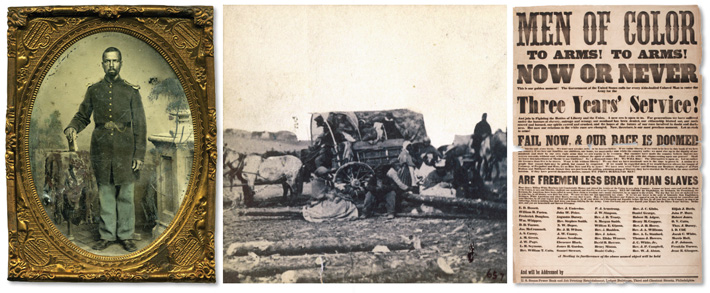

During the Civil War, soldiers were able to send pictures of themselves home for the first time in history. Therefore, it was not surprising to find that photographs were being taken at Camp Nelson. Prior to his recent excavations, Camp Nelson National Monument archaeologist Stephen McBride had found documentary evidence of at least four photographers working at the camp. One was G.W. Foster, who was contracted by the army and took photos to send with military reports to show how orderly the camp was.

The newly discovered photo studio has added Cassius Jones (“C.J.”) Young, the son of a Lexington portrait painter, to the list of Camp Nelson’s photographers. “The fact that we have so many photographers working at the camp really speaks to the prevalence and popularity of photography in the Civil War,” McBride says. McBride identified Young’s studio based on the brass stencils that he used to sign his work, most of which contained some kind of error and were likely discarded practice plates. His team also found brass sheets used to make stencils for soldiers’ photos, which were marked with their name, unit, and company, as well as mats, glass plates, and chemicals for the developing process.

It was, of course, not only soldiers whose pictures were taken during the 1860s. “One of the most photographed people of the era was Frederick Douglass,” says McBride. “Douglass wrote several articles on photography and called the era the ‘Age of Pictures.’ He thought that photography was an important social development because only people, not animals, could appreciate photographs. Soldiers and recently emancipated men were Americans, and they wanted to document their new status and to share it. A photo meant you were a person, and thus that African Americans were people, too.”

On the basis of the animal bones and archaeobotanical evidence that has been unearthed, McBride says that what meat the USCT enlistees did eat consisted of relatively poor cuts of beef, such as ribs and hind shanks, supplemented with pork hams and hocks, and that they consumed a great deal of legumes, particularly beans, cowpeas, and lentils. For refreshment, they had whiskey, beer, and champagne, despite the fact that they were not officially permitted to drink. “Some of the most surprising artifacts we uncovered in the encampment were those associated with women and children, including colored glass beads, a brooch, a barrette, and porcelain doll fragments,” says McBride. “This indicated that wives and children were living with their soldier husbands and fathers, which was strictly against army policy.” The wives and children of soldiers are mentioned rarely, if ever, in records of the time, so these artifacts are some of the only evidence of Camp Nelson’s shadow population.

In all, 5,700 African American soldiers enlisted at Camp Nelson and at least 5,000 more were trained there. Although the army discouraged the men from bringing their wives and children with them, the soldiers’ families nonetheless continued to arrive. “I think that we underestimate these women’s will to chart their own path to freedom,” says historian Brandi Brimmer of Spelman College. “Black men’s path is through military enlistment, even under the Confiscation Acts, but slave women’s route is very different. They don’t have a policy in place to support them and they have to find their own way.”

At first, most of the refugee families lived in huts and small cabins they hastily built themselves. They received no food rations or care. “The army really didn’t know what to do with them,” McBride says, “especially because, unlike their enlisted husbands and fathers, they were still technically enslaved.” Even though the Union was not prepared to allow women and children into facilities like Camp Nelson, they went anyway, took up residence, and were often kicked out. Between June and November of 1864, on nine different occasions, according to Taylor, Camp Nelson’s women and children were expelled. One of the most disastrous of these regular expulsions occurred in late November of 1864, when many women and children died of exposure and malnutrition during a particularly cold and windy month. “There is no bureaucracy to chronicle these people’s illnesses, and their death is a direct result of their experiences as refugees,” says Downs. “Their deaths, and those of others who died in the camp, were not recorded. They were anonymous, their lives and deaths not named.”

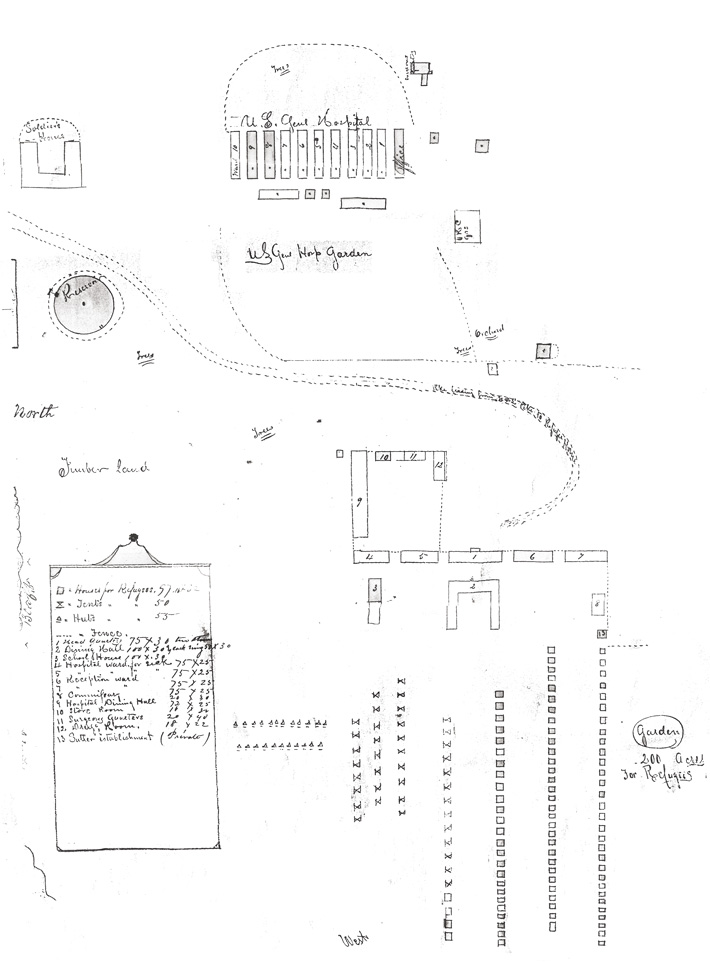

But families escaping slavery kept coming. “Black men made it clear they were not going to continue to enlist without a path to freedom for themselves and their families,” says Brimmer. In December of 1864, the army began to build the Home for Colored Refugees at Camp Nelson. The status of African Americans was still very much in question as far as Union officials were concerned: Were the women and children legally attached to a soldier? What constituted a legal marriage between enslaved or formerly enslaved people? What about the aging women and men unfit to serve? Nevertheless, more than 3,000 people were allowed into the home during the last year of the war. “While it is true that the camp became more open to women and children,” says Taylor, “and that there were new cottages, an opportunity for schooling and to go to church, and a chance to work and build a new life, the camp was still a significant source of turbulence, danger, violence, illness, and death.”

While little archaeological evidence of the huts and cabins of the original women and children’s camp remains, McBride has been able to reconstruct what the Home for Colored Refugees looked like through excavation, archival research, and by reviewing photographs. The Home consisted of four dormitories or wards, an office, a two-story school, 97 duplex cottages for nuclear families, and, when the cottages filled up, 60 tents supplied by the army. At the pre-expulsion site of the huts and cabins, McBride found a great deal of evidence of food preparation including ceramics used for serving food, cast-iron kettles, and fragments of steel cooking utensils, as well as evidence of chimneys used for heating and cooking. He also uncovered evidence of food consumption—bones from poor-quality cuts of pork, mediumto poor-quality cuts of beef, chicken bones, and a small number of rabbit and fish bones, as well as liquor bottles. At the Home for Colored Refugees, however, the team found little to no evidence of either food preparation or consumption. Instead, there was a large mess hall where, explains McBride, the army strongly encouraged women and children to eat all their meals rather than cook for themselves.

McBride also uncovered some evidence of how women earned money to buy food and clothing. In the northwest section of the encampment, he unearthed fireplaces and a large concentration of cast-iron kettles and an iron, as well as a great number of both intact and broken buttons, seed beads, and hooks and eyes, all evidence of a laundry facility dating to before the November 1864 expulsion. “Especially early on, doing laundry was, along with cooking, one of the primary ways escaped slaves bartered or earned money for food,” says McBride. “They didn’t know what would happen to them, but they thought there was a chance of attaining freedom and had to adapt quickly to their situation.” But, they were still enslaved.

On March 3, 1865, the wives, children, and mothers of USCT soldiers were finally emancipated by Congressional act. Five weeks later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. For all intents and purposes, the Civil War was over. The USCT had played a crucial role, having been involved in 41 major battles and 449 skirmishes. “The black soldiers compensated for a lack of training with extraordinary valor,” says Glatthaar. “In the face of assumptions that they would be cowardly, they could not afford to fail.” For African American slaves, enlistment meant freedom for themselves, and, in some cases, their families. But, despite the Union victory, even after the war, their situation in Kentucky was nearly as difficult as it had been before and during it. “White Kentuckians did all they could to try to extend the system of slavery and to shut down the paid labor market for black men and women,” says Taylor. After the war, Camp Nelson remained an important African American community even as its residents were still being kidnapped and enslaved. On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment was ratified, abolishing slavery throughout the United States. Nevertheless, in the 1870s, 7,000 African Americans would flee the state.

The impact of the USCT on the outcome of the war and the opportunity it provided for liberation cannot be overstated. On September 26, 1864, Elijah P. Marrs, a slave who had been born in January of 1840 in Shelby County, Kentucky, to a free man and an enslaved mother, enlisted in Lexington along with 27 other men. On their journey from their homes to the city, they carried with them 26 war clubs and one rusty pistol, and were accompanied by a Newfoundland dog for a spell. Marrs recalls in his memoir that he was immediately marched out onto Third Street to Taylor Barracks and mustered to Company L, Twelfth U. S. Colored Artillery, which was assigned to Camp Nelson. “This is better than slavery, though I do march in line to the tap of the drum,” Marrs writes. “I felt freedom in my bones, and when I saw the American eagle, with outspread wings, upon the American flag, with the motto, ‘E Pluribus Unum,’ the thought came to me, ‘Give me liberty or give me death.’ Then all fear banished. I had quit thinking as a child and had commenced to think as a man.”