The Wind River Range in the Rocky Mountains stretches 100 miles across northwestern Wyoming and the Continental Divide, extending from the thick pine forests of Yellowstone National Park toward the vast grasslands of the Great Plains. From the river valleys and lakes below, the peaks of the mighty “Winds” rise toward the sky, reaching 13,000 feet above sea level. These granite towers pierce the clouds and are surrounded by high-altitude plateaus dotted with tundra and remnants of Ice Age glaciers. From a distance, they appear imposing, barren, and hostile, but closer inspection reveals a vibrant scene—herds of bighorn sheep traversing the horizon, marmots peeking up from boulder fields, and clusters of ancient whitebark pines standing watch over it all.

On the outskirts of a scraggly whitebark pine forest at 11,000 feet above sea level in the northern stretch of the range, a plume of smoke rises from a campfire as lunch is prepared in cast iron cookware over the open flames. Tents are spread out across the alpine meadow, and the whinnies of horses echo against nearby cliffs. It is a scene reminiscent of a nineteenth-century frontier camp, except for the presence of a bright yellow surveying instrument and the metallic ting of trowels as archaeologists scrape them against the pebbly soil. The site, known as High Rise Village, is perched on a hillside that would make a challenging black-diamond ski run. It was a large settlement occupied by the seminomadic Shoshone people from around 4,000 years ago until the nineteenth century. Discovered in 2006 by University of Wyoming archaeologist Richard Adams, High Rise Village was the first and largest of nearly two dozen high-elevation villages to be identified in the Wind River Mountains, and has provided new insight into how prehistoric people thrived in the high alpine zone of the Rocky Mountains.

Alpine archaeology is a relatively new field in North America. Conducting fieldwork in remote high-altitude areas is expensive and physically demanding. “Before the advent of modern, lightweight camping equipment, it often wasn’t possible to run prolonged projects in the mountains,” says Adams. As a result, the craggy peaks and wind-whipped ridges of the American West long remained a blank spot on the map of prehistoric North America.

In the 1960s, Colorado State University archaeologist Jim Benedict identified miles of stone walls along the plateaus of Colorado’s Front Range, evidence of communal game drives constructed to corral large herds of bighorn sheep. Around two decades later, University of California, Davis, archaeologist Robert Bettinger discovered multiple alpine villages near 12,000 feet in California’s White Mountains. Farther east, at 11,000 feet in Nevada’s Toquima Range, David Hurst Thomas of the American Museum of Natural History found the Alta Toquima site, remains of a massive prehistoric village high in the alpine tundra consisting of dozens of depressions known as house pits. The discovery of such substantial sites in remote alpine settings was astonishing to many scholars across the western United States who had long considered the mountains too hostile for sustained human occupation. What led ancient people to build at such high elevations was an open question—did they actively choose to live in the alpine tundra, or were they forced there by factors such as population pressure or climate change? This question has fueled debate among alpine archaeologists worldwide, and each summer more researchers venture high into the mountains seeking answers.

In the fall of 1995, avocational archaeologist and hunting guide Tory Taylor tripped over a bowling ball–size blue rock while taking shelter under some trees during a thunderstorm in the northern Wind River Range. Turning it over, he recognized the object as a bowl that had been carved out of soapstone. Before this, no archaeological work had ever been attempted in the Winds. Several years later, the news of Taylor’s find reached Adams, who was researching soapstone artifacts found throughout the Rocky Mountains. Adams contacted Taylor and, upon learning more about the discovery, planned a survey expedition with him to investigate the area.

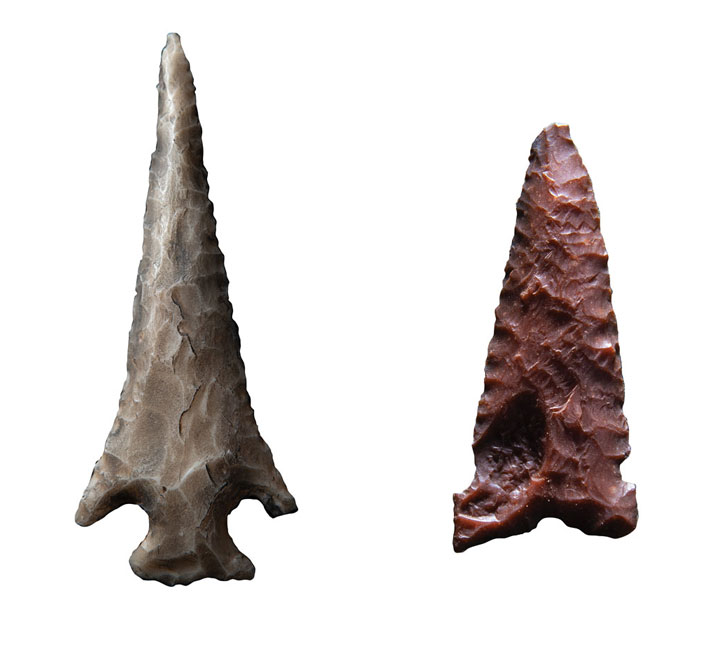

In 2003, Adams, Taylor, and a group of volunteers hiked deep into the Wind River Mountains, with their equipment on horseback, for the first field season of what would become a project that is still going on 16 years later. During the initial surveys, the team recorded more than a dozen prehistoric sites above 10,000 feet. Scattered across the surface of the alpine tundra, the football field–size sites included tens of thousands of chert flakes, eroding hearths, hundreds of complete tools including scrapers, knives, and projectile points, and broken ceramic vessels and soapstone bowls. The size and number of sites discovered above the tree line indicated that hunter-gatherers had frequented the alpine terrain since the end of the Ice Age and that people had a much deeper history in the Wind River Range than had been previously realized.

While the large number of artifact-rich sites Adams discovered offered proof that ancient people had traveled in the Winds, questions remained about how the sites were actually used. Did they reflect occasional forays to higher elevations for hunting and foraging, or did they, as Adams speculated, suggest that people had established an enduring society in the mountains?

In 2003, when Adams investigated a wickiup, or wooden tepee, that had recently burned in a forest fire, he made what he recalls as one of the most startling discoveries of his career. Where the small wooden structure had once stood amid thick grass and pine trees, the forest fire had revealed a lodge pad, a stone-lined circular platform cut out of the hillslope that had once served as the foundation for a wooden house structure. Thousands of artifacts were eroding out of it. Adams realized that the lodge pad resembled structures found in the alpine villages excavated by Bettinger in the White Mountains and Thomas in the Toquima Range. The discovery showed that prehistoric people hadn’t just occasionally traveled in these mountains, but had actually built at least one semipermanent settlement. “Alpine villages were considered to be an exclusively Great Basin phenomenon,” Adams says. “We were surprised to find that they likely existed in Wyoming, too.” While the find established that alpine villages may have existed in the Winds, Adams needed more evidence to determine if they were common, or if the lodge pad found at the site of the burned wickiup was simply a fascinating anomaly.

In fall 2006, Adams was exploring a newly burned alpine forest with a team of volunteers. During a lunch break on the side of a steep slope dotted with granite boulders, Joyce Evans, an experienced avocational archaeologist, noticed a platter-size piece of sandstone that stood out against the surrounding rocks. Evans picked up the stone and realized that it was a heavily used grinding stone, or metate. It was clear evidence that prehistoric people had not only settled on this slope, but also had invested long periods of time there, as it would have taken several generations of grinding to make a rough sandstone so smooth and polished. Walking a few hundred feet from the rest of the team, Evans found a flat platform cut into the hillside that was full of chert flakes, and then another with a projectile point, and still more encircled by stone walls. Unbeknownst to them, Adams and his team had sat down for a rest in what turned out to be the largest alpine village yet discovered in the Rocky Mountains.

Over the next several years, Adams and his team mapped and excavated the new site, which they dubbed High Rise Village after the 300-foot distance between the settlement’s lowest point and its highest, equivalent to a 30-story building. Their excavations revealed that the site was massive, with more than 60 lodge pads cut into the steep mountain slope. The discovery of such a large village took archaeologists aback. “Finding Alta Toquima and the White Mountain villages were such big surprises, we assumed that they were two of a kind and nobody was going to find any others,” says Thomas. “So it was another large surprise when a new village appeared in the Wind River Range.”

Despite the recent forest fire, the buried archaeological remains at High Rise Village, including the remains of tepee- and log cabin–shaped wooden wickiups that once stood atop the lodge pads, were exceptionally well-preserved. Many of the lodges also contained well-preserved hearths. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the hearths showed that people lived at High Rise Village as early as 2000 b.c., and that it was occupied continuously until about a.d. 1850. The artifacts the team recovered from the nine-foot-wide circular pads numbered in the tens of thousands, and included hundreds of chert and obsidian projectile points, as well as knives, scrapers, drills, bone needles, grinding stones, soapstone pendants, red ochre nodules, and broken ceramic vessels. The array of artifacts was typical of those made by the Mountain Shoshone people, also known as Sheepeaters after their affinity for hunting sheep. It’s likely that a band of that tribe inhabited the village.

Adams and his team suggest that multigenerational families spent their time on the mountain hunting, foraging, processing pine nuts, and making and repairing a variety of tools. The excavations also indicated an intriguing level of social organization at the site, and that the village’s seasonal inhabitants may have used different lodge pads for particular activities. The artifacts from one lodge, for example, consisted of stone tools used to make projectile points, whereas another lodge contained only artifacts associated with butchering meat and cleaning hides. A third contained only artifacts and flakes left from making bifaces, multipurpose stone tools used for cutting and scraping. “While we have only excavated a portion of the 60-plus lodges at High Rise, based on our current sample size it does appear that there was craft specialization or some division of labor at the site,” says Adams. The team’s discoveries suggest that the seminomadic inhabitants of High Rise Village had a complex social structure that they maintained even as they moved high into the mountains.

When not excavating at High Rise Village, Adams and his team ventured farther into the Wind River Range. They recorded nearly 100 prehistoric sites, identified quarries where soapstone was mined, and found four more, smaller, alpine villages. After years of working at High Rise Village, Adams became adept at spotting the faint remains of lodge pads. “I realized that the majority of lodge pads were informal and relatively difficult to recognize,” Adams says. “There was a good chance that before High Rise, we had walked right through several villages.” Adams returned to several previously identified sites, including the burned wickiup, and discovered that many were part of large prehistoric villages that had been overlooked. In addition to finding that alpine villages were much more prevalent than previously known, Adams and his team realized that the sites were all located in whitebark pine forests, on inclined sunny slopes, and at 10,500 to 11,000 feet above sea level. It was almost as if ancient people created one alpine village and replicated it atop other mountains throughout the northern Winds.

Given the prevalence of grinding stones found at the sites and their location in whitebark pine stands, it appeared that the villages’ earliest inhabitants chose their locations in order to harvest and process pine nuts, one of the fattiest food sources available to prehistoric people in Wyoming. To test this hypothesis, the team created a predictive model incorporating satellite, terrain, and environmental information over a large area to identify the best locations for people to harvest the nuts. The team then set out on horseback, toward the higher barren slopes of the Continental Divide, in search of the predicted sites. Using the model as a guide, they traversed turquoise glacial rivers, steered clear of grizzly bears, and navigated miles of alpine boulder fields. Ultimately, they identified 14 more prehistoric villages exactly where the model had predicted they would be.

Even after the team discovered that the alpine villages were so numerous, they still wondered why people would want to live long-term in such a severe environment as the Wind River Range when trout-filled lakes dotted the foothills and bison herds roamed the prairie below. Some scholars view high elevations as a difficult landscape where food was generally scarce, unpredictable, and required a great deal of energy to acquire. This would suggest that ancient people may have chosen to build villages in the mountains to escape rising population pressure or prolonged droughts in the surrounding lowlands. “Because high-altitude archaeology is in an extreme environment, it acts as a barometer on the state of a wider human system,” says University of Wyoming archaeologist Robert Kelly. He believes that the occupation of high-altitude villages waxed and waned depending on low-elevation conditions. “If there was a reduction in important resources at lower elevations,” he says, “then groups might have expended the extra energy to acquire other resources from high elevations.”

But other archaeologists, including Adams, believe the resources available in the mountains drew prehistoric people regardless of conditions in the valleys below, especially during certain seasons. Around mid-July in Wyoming, many low-altitude sources of water dry out, making it challenging for plants and animals to survive. The mountains during this time, however, teem with edible plants and herds of deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. For groups like the Shoshone, who were familiar with the seasonal growing cycles of plants and migration patterns of animals, the mountains would have offered bountiful opportunities for hunting and gathering throughout most of the summer. “I suspect that, as soon as the snow melted, people hiked into the mountains to harvest springtime root crops, then berries and tubers later in the summer, and whitebark pine nuts in the fall,” says Adams. In his view, high elevations provided an environment that was no more difficult to survive in than the surrounding lowlands and required only a familiarity with the landscape.

Whether the Mountain Shoshone were pushed or pulled into the mountains, the Wind River Range held great significance for them. The mountains played a central role in their mythology and remain important to their descendants today. “The Winds provide for our people in many ways—from the snow-capped peaks that provide us with water to the abundance of wild game, they have always given us what we need to survive,” says linguist Lynette St. Clair, a member of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe. “We hold them in high regard, take only what will sustain us, and offer our prayers as an exchange.” In the late 1800s, the remaining bands of Mountain Shoshone were moved out of the mountains and onto the nearby Wind River Reservation. As they assimilated into a larger and more diverse Shoshone community, many of their stories were lost. Adams and his team now hope that their work may help recover forgotten aspects of the mountain people’s history.

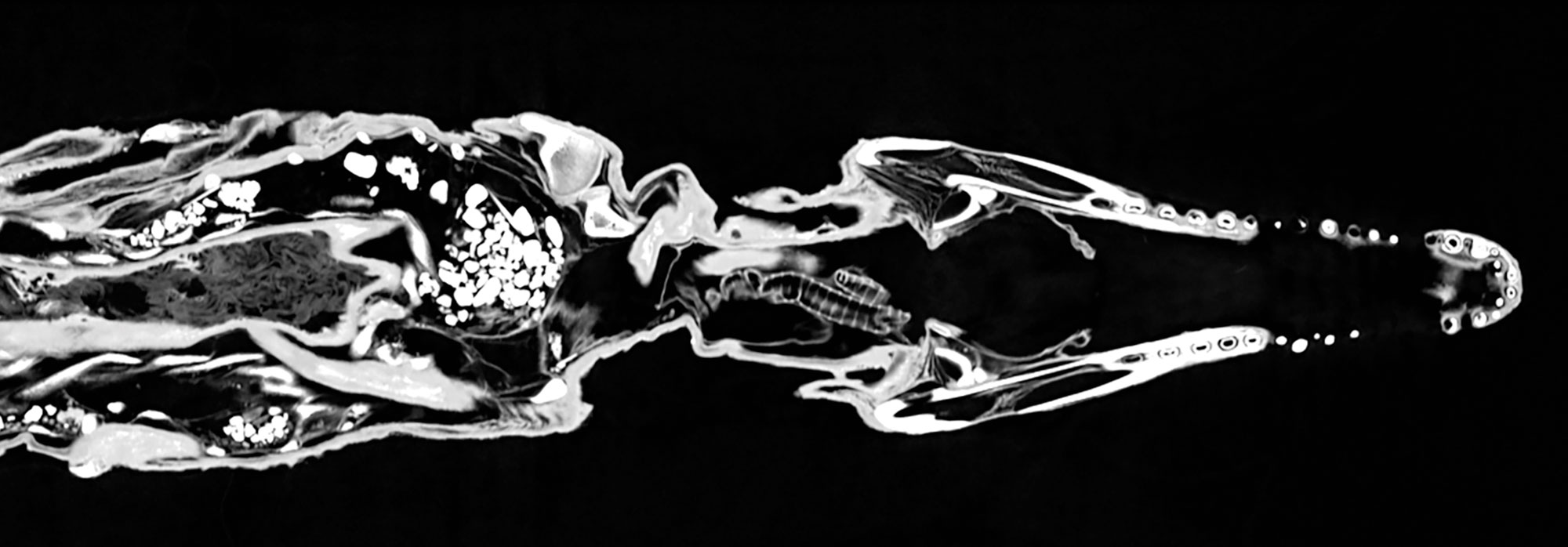

One promising avenue of research is being pursued by environmental archaeologist Rebecca Sgouros of the nonprofit Paleocultural Research Group. By analyzing residues absorbed into artifacts, she and her colleagues hope to connect the archaeological record to Shoshone oral tradition. “We know that there were plenty of edible resources available to people in the mountains,” Sgouros explains, “but what if we could know specifically what they were eating and what plants and animals were of special importance?” Sgouros has found residues on metates from the alpine villages that show that people used them to process pine nuts, animal fat, berries, and dried meat—the ingredients for pemmican, a traditional Native American food. Lipids extracted from pottery vessels also found in the alpine villages show evidence that they were used to cook elk, moose, and bear with chokecherries, biscuit-root, and leafy greens. Several soapstone vessels contained residues of pine nuts, chokecherries, rendered fat, and trout, a combination that matches the recipe for a Shoshone fish stew recorded in the early nineteenth century. “We are seeing evidence of foods that we know were historically important to the Shoshone,” says Sgouros. “And we are getting to look beyond simple ingredients and actually get glimpses into cuisine and culture.”

After 17 years of fieldwork, thousands of miles hiked, and hundreds of nights sleeping under the stars, Adams and his team still hope to better understand how people’s relationship with the Wind River Range evolved over time and what daily life was like for those who chose to live in the high mountains. Once the spring snow melts and bighorn sheep begin to return to their summer range, the team will saddle their horses, triple-check the coffee supply, and venture once again onto the trail and into the towering peaks of the Winds.

Slideshow: Exploring the Life of Ancient Mountaineers

Over the last two decades, archaeologists led by the University of Wyoming’s Richard Adams have discovered dozens of sites high in the mountains of Wyoming’s Wind River Range. Previously, scholars believed that high altitude environments were not places prehistoric people would have settled. But archaeologists are now finding that ancient sites abound in the mountains of the American West. All the following images of the fieldwork conducted in the Wind River Range are courtesy of archaeologist and journalist Matt Stirn.