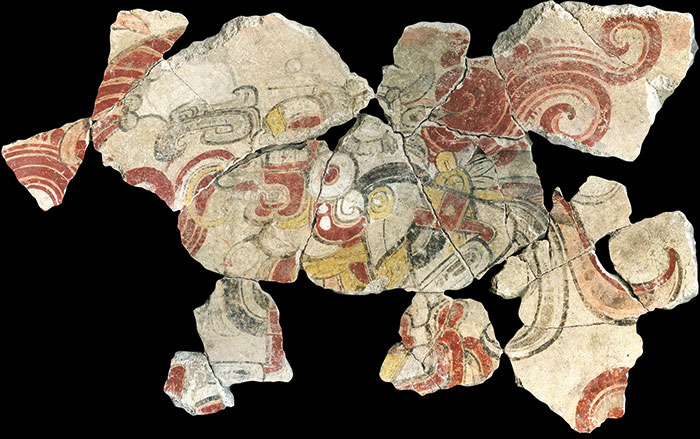

A mound in Syria now covered by a lake may have been a monument to the war dead of an ancient Mesopotamian settlement based at a site called Tell Banat. The six-story structure was built of lime-rich mud and gypsum that glistened in the sunlight. Known as the White Monument, it was excavated in the 1990s, before construction of a dam flooded it. University of Toronto archaeologist Anne Porter, who co-led those excavations, recently tasked her undergraduate students with revisiting the expedition’s copious notes. “The virtue of having some distance in time is that you aren’t locked into expectations of what the data might tell you,” says Porter.

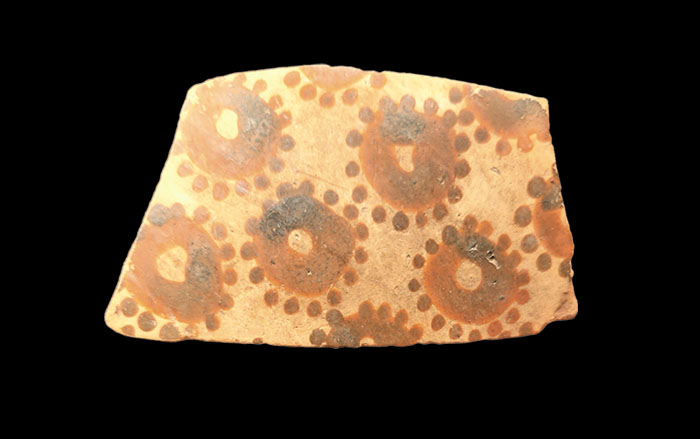

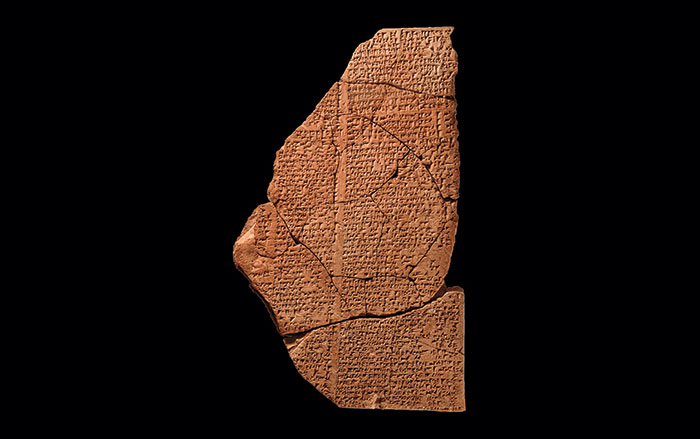

The students found that artifacts and human and animal burials recovered from the last stage of the White Monument’s construction, around 2450 B.C., were laid out in deliberate patterns. The remains of adults and teenagers who had originally been buried elsewhere were carefully arranged in the monument near deposits of clay pellets that were used in battle as sling projectiles. Some remains were buried near the skeletons of kunga, donkey-like animals that pulled war wagons in ancient Mesopotamia. Among the artifacts found at the monument were a clay figurine resembling a donkey and a model of a war wagon. “We now believe this was a memorial to members of a war party who served in a local conflict,” says Porter. The White Monument would have been visible to the people of Tell Banat and other settlements throughout the area, and may have embodied the story of a battle remembered for generations.