In fall 2007, Glenna Wallace, chief of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, visited the Octagon Earthworks in the central Ohio city of Newark while attending a lecture series at the Ohio State University in nearby Columbus. Wallace is a seasoned world traveler, but she was nevertheless astounded by the Native American mounds, which were built 2,000 years ago by her people’s ancestors. The eight walls of the Octagon Earthworks’ namesake structure each measure five to six feet high and about 570 feet long. The Octagon Earthworks are part of the Newark Earthworks, the largest known set of earthworks that include circular, square, and octagonal enclosures. The mounds’ positions correspond to lunar movements, and the structures align with points at which the moon rises and sets over the course of the 18.6-year lunar cycle.

Tempering Wallace’s elation that day was the reception she received as she proceeded across the golf course where the mounds are situated. Irate golfers made it clear that she wasn’t welcome on the grounds, which, under a decades-old arrangement with the state, were open only on rare occasions to visitors interested in the earthworks. “I was just totally astounded, amazed, disappointed, hurt, all within five minutes,” Wallace says.

The Newark Earthworks—which are a National Historic Landmark and Ohio’s official prehistoric monument—are part of the larger Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks complex, which encompasses other sites including the Fort Ancient Earthworks in southwestern Ohio and five earthworks in Chillicothe in southern Ohio. Combined, they represent the largest concentration of ancient Native American monumental landscapes in North America. Their creators are known as the Hopewell people, although this designation doesn’t reflect what the builders called themselves, which is unknown. The Hopewell are the ancestors of a number of federally recognized tribes in Ohio—including the Chippewa, Delaware, Kickapoo, Miami, Ottawa, Peoria, Potawatomi, Seneca, Shawnee, and Wyandot—says Alex Wesaw, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi and director of American Indian relations at the Ohio History Connection, the state’s historical society.

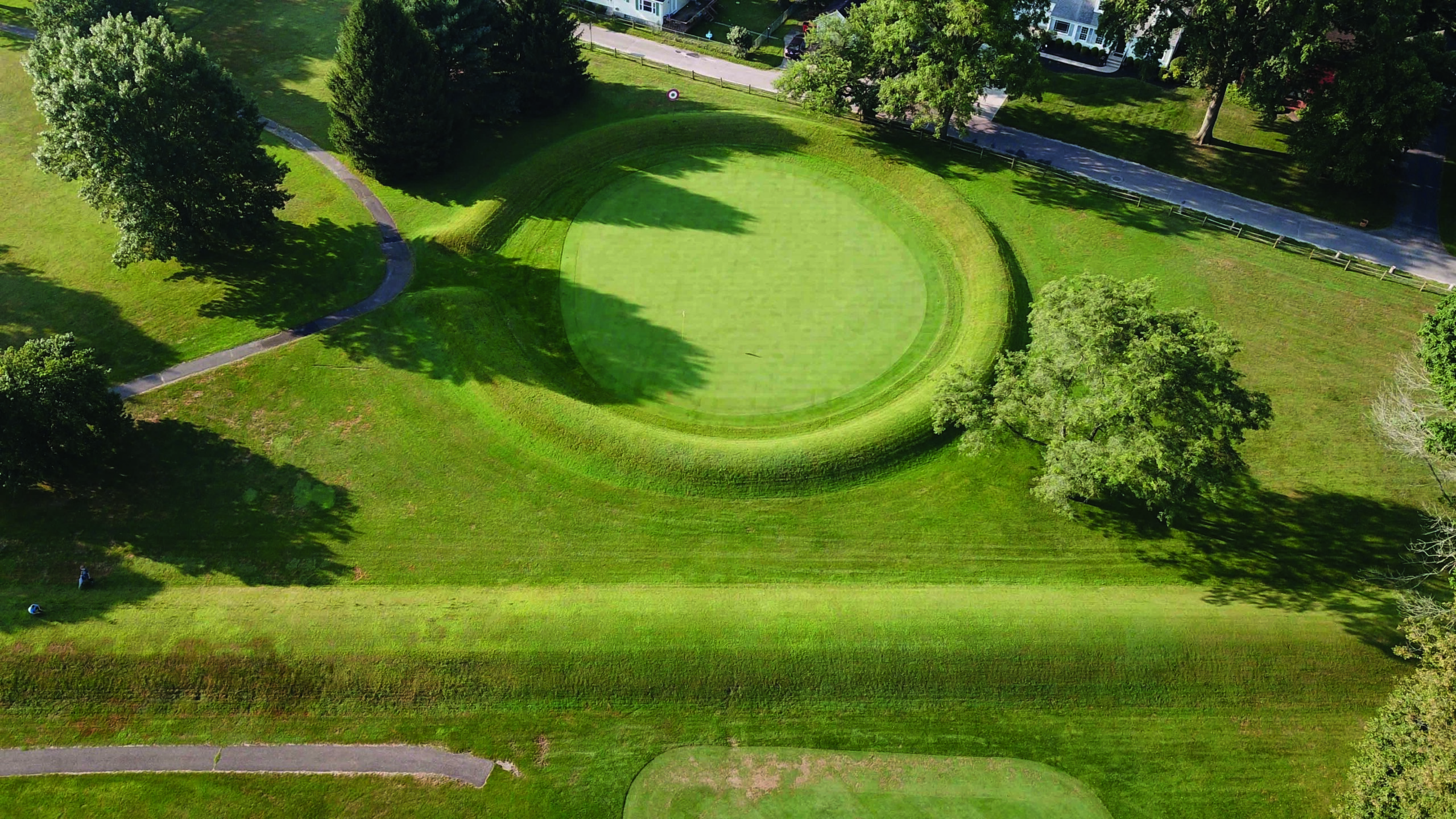

The modern history of the Octagon Earthworks reflects changing attitudes toward such monumental Indigenous structures in the United States. Efforts to protect the earthworks began in 1892, when voters in Licking County, where they are located, approved a tax increase to provide for their preservation. Between then and 1908, the site was used as a state militia encampment. In 1911, the area was developed as a golf course, and the state leased the 134-acre property to Moundbuilders Country Club beginning in the 1930s. Although the lease wasn’t set to expire until 2078, the state sued several years ago to reclaim the property by eminent domain. Thanks to a ruling in December 2022 by the Ohio Supreme Court, access to the earthworks is now set to expand dramatically. After a trial to determine how much the state must compensate the country club, control of the site will be permanently transferred to the Ohio History Connection.

Archaeologists still have many questions about the Octagon Earthworks, including how often ancient people visited them, how the Hopewell created such precise astronomical alignments without sophisticated surveying instruments, and whether they built wooden structures there. All future projects designed to explore these and other questions at the site will have to be approved by Native American representatives. “People need to write with us, not about us,” says Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma. “Don’t work on us—find out what work we want done and what we can do collaboratively.”

As the state and its Native American partners plan for the future of the Octagon Earthworks, relandscaping the site to remove traces of the golf course should be a top priority, says Diane Hunter, a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and its tribal historic preservation officer. She hopes that more research into the earthworks’ relationship to the skies will be a priority. “With full access to the site,” Hunter says, “there may be a lot more to learn about how it’s aligned to the sun, the moon, the stars.”

The precision with which the Hopewell built their mounds has long amazed archaeologists. For example, the Octagon Earthworks’ Observatory Circle has the same area as a nearby square enclosure. Observatory Circle also has the same diameter—1,054 feet—as two circles at other Hopewell sites in Ohio. Wallace says the geometric and astronomical expertise of those who designed and built these structures two millennia ago obliterates forever the idea that Native Americans lacked sophisticated scientific and engineering knowledge. “The Octagon Earthworks is our history,” she says. “It’s our culture. It’s our reverence for our ancestors. We stand on their shoulders: Whatever progress we have made, we wouldn’t have been able to do it had it not been for our ancestors.”