There are a few things you can’t understand about the World War I battlefield at Gallipoli until you stand on it. One is just how compact it is. The coast of the Aegean, where Allied forces from Australia and New Zealand landed on April 25, 1915, is less than a mile from the front lines. From a few places, it is possible to see almost the entire battlefield, where Ottomans fighting for the Central Powers held off the Allied attack for eight grueling months. No-man’s-land, the strip of scarred earth between the opposing armies’ trenches, was as little as 30 feet wide in some places—close enough to hurl a stone at your enemy, smell his food cooking, or overhear a casual conversation. The battle was condensed and, during the prolonged stalemate, grew familiar, even intimate. It also took place in three dimensions. At Quinn’s Post, where no-man’s-land was at its narrowest, both sides clung to either edge of a single ridge, with steep drops behind them. It is deceptive, difficult terrain to read under the best of conditions; in the fog of war, with machine-gun fire, snipers, and a constant rain of shrapnel, it must have been utterly confounding.

Today, Second Ridge Road runs through this no-man’s-land, linking dozens of monuments and graveyards. Traces of many of the battle’s trenches, dugouts, and tunnels still lie deep in the thick roadside brush. For the past several years, an international team of archaeologists has clawed through this vegetation and scrambled up and down these slopes looking for patterns in the surviving earthworks, for fragments that have survived a century of scrap- and souvenir-collecting, and for a sense of what life in the trenches was like for tens of thousands of young men. This section of the battlefield is commonly referred to among Westerners as Anzac (Arıburnu in Turkish), so named for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps soldiers (ANZACs) who fought here. Though the battle is of critical historical importance to three modern nations—Turkey, Australia, and New Zealand, all represented in the survey effort—it has never before been investigated with modern archaeological methods and techniques. “The actual site is something that is out there,” says Antonio Sagona, the project’s field director, of the University of Melbourne. “But it is not really understood.”

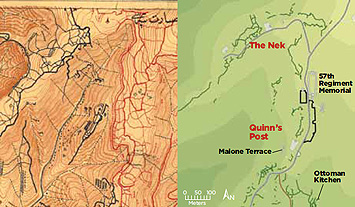

A quarter mile up the road from Quinn’s Post is The Nek, where another cemetery occupies no-man’s-land. Ian McGibbon, a historian from New Zealand and member of the field team, begins picking his way through the thicket of rhododendron beyond the cemetery and into the Allied trenches that sprawl across a small plateau called Russell’s Top. McGibbon hops down into a depression that marks one of the ANZAC trenches. “All these trenches are going to go in 50 years,” he says. They have slumped in, but, at least for now, roots preserve the shapes and patterns of the ANZAC redoubt. The trenches were once eight feet deep, but the protection they provided from falling shells, shrapnel, and snipers on higher ground was, at times, limited. “Nowhere on Anzac were you safe,” says McGibbon. “You can’t understand it until you stand here.”

The trench winds—Allied trenches were made to zigzag, to lessen the impact of shrapnel—into a more open depression, a dugout that served as a command center or waiting area. The trench that picks up on the other side once stopped just short of a cliff to the north, but the end has eroded, so it simply runs out into space, providing a dizzying view of the plains and salt lake to the north. The preservation of these remains is astounding, given the fate of most WWI battlefields, long since converted to farmland. Here, topography has preserved the battle in state. “It is the best-preserved World War I battlefield, and one of the best-preserved battlefields in the world, period,” says Sagona.

The weblike trench network is hard to parse from ground level, but the team has mapped many of these features to show how the ANZACs held the area, despite little chance for forward progress. To the east are eight lines of Ottoman trenches on higher ground that the team has also mapped, somewhat more eroded than the Allied ones because they lie on a slope. “Futility, extreme bravery, and incompetence,” McGibbon says when describing the battles at The Nek.

The project that Sagona, McGibbon, and others are working on is called the Joint Historical and Archaeological Survey, and it began in 2005 with high-level diplomatic negotiations between the Turkish and Australian governments. A proposal involving all three interested nations was approved, with Sagona, whose specialty is pre-Classical antiquity, as field director, and with the project permits held by historian Mithat Atabay of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University in the nearby city of Çanakkale. The goal is to pull together landscape archaeology, artifact analysis, and historical data into a new assessment of the site, and how it has changed, in time for the centennial in 2015. The team made its first reconnaissance trip in 2009. “I was daunted by it,” says Sagona.“When I realized the steepness of the terrain, that the vegetation was three times as tall as the archaeologists and really impenetrable, I realized we had to change our approach.”

They decided to focus on the Second Ridge, where activity was particularly concentrated, and adapted archaeological survey methodology to the challenging setting by walking long transects and following features, rather than dividing the whole battlefield into a single grid. Despite the difficulties, the team has already begun to see patterns and has new insights into a battle that was well documented in its time and has been thoroughly mythologized by three nations since.

The Gallipoli peninsula is separated from the Turkish mainland by the Dardanelles, the strait that leads from the Mediterranean, via the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus, to the Black Sea. The waterways mark the boundary between Europe and Asia, but also connect the continents by water, a sea route that has been coveted since antiquity. The peninsula had been occupied by the Greeks since at least the seventh century b.c., and has been hotly contested since. It was also mentioned in the Iliad (the Gallipoli city of Sestos is mentioned as an ally of Troy, which lies just across the strait), and played a key role during the height of the Ottoman Empire and the Balkan Wars.

In the early months of WWI, the Allies consisted of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia—a coalition split, geographically, by the Central Powers, which included the German and Austro-Hungarian empires. A sea supply route to Russia, through the Turkish straits and the Black Sea, was of critical strategic and military value. The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the straits, was the wild card. German coffers trumped Allied ones, and by late 1914, the Ottomans counted themselves among the Central Powers. In early 1915, the Allies began a naval assault on the Dardanelles, the brainchild of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill. Ottoman mines served to turn away the attack, and a subsequent plan was hatched for a ground attack to take out the Ottoman mobile artillery to provide an opening for Allied minesweepers and ships to rush up the straits.

The invasion began on April 25, 1915, with two offensives: a British landing at the southern end of Gallipoli (known as Helles), and an ANZAC landing on the Aegean coast to the north, where they were to fight across the peninsula and cut off Ottoman supply routes and reinforcements. The ANZACs stormed the beach and moved up the ridges, supported by shelling from warships, and dug into foxholes that were then connected to form the first trench line. The Ottomans held their ground, even as they ran out of ammunition and both sides suffered heavy, near-total casualties.

“Men, I am not ordering you to attack. I am ordering you to die. In the time that it takes us to die, other forces and commanders can come and take our place,” is reportedly the order given by Ottoman commander of the 19th Division, Mustafa Kemal, the man later granted the name Atatürk, or “Father of the Turks,” the country’s first president and national father.

Despite a few offensives, the battle devolved into a stalemate so static as to feel almost rote. As the months passed, the battlefield became notorious for its squalid conditions, including decaying corpses, bad sanitation, and a dysentery outbreak. There was baking heat, drowning rain, and even a blizzard. It is said that the proximity of the two sides and their shared hardship led to an unusual camaraderie, with laundry hanging on barbed wire and gifts such as dates and cigarettes tossed between trenches. The Allied retreat came in stages from December 1915 to January 1916. It was, ironically, the most successful part of the campaign, a secret evacuation that resulted in little loss of life despite dire predictions of casualties. Of the just more than 1,000,000 soldiers involved in the battle—most from Britain and Turkey, but including the French, Australians, New Zealanders, and even Indians—approximately a third were counted as casualties, with around 130,000 dead, according to the Australian Department of Veterans’ Affairs. When an official Australian historian, Charles Bean, visited the Second Ridge in 1919, he reported bones and equipment “scattered everywhere.”

In addition to Bean’s reports and a series of maps by Turkish surveyor Mehmet Şevki Paşa in 1916, there is an extensive documentary record from both sides of the battle, from orders and battlefield maps to letters and diary entries. The archaeological team is, of course, aware of this material, but has chosen to stay away from most of it until the archaeological work is done. “Even though we have a huge amount of textual evidence, maps and so on, we’re using that as background, but we’re not using those to guide us in our survey,” says Sagona. “What we really want to find out, and where archaeology is helping us enormously, is to give us a clear indication of life in the trenches. More than anything, it gives us an independent source to understand the Gallipoli Campaign.”

Eventually they will integrate the documentary sources with their work in time for 2015’s ANZAC Day—the 100th anniversary of the landing, on April 25, when Australians will descend on Gallipoli by the tens of thousands for solemn ceremonies and a little revelry.

Walking south along Second Ridge Road from The Nek and Quinn’s Post, to the right is Johnston’s Jolly, where well-preserved trenches are accessible to tourists, with a Turkish position called Kırmızı Sırt across the road. A little farther on, at Lone Pine, where there is a large Australian monument and graveyard, McGibbon dives back into the brush, picking his way through to tunnel openings the team has already recorded. “Most of the action took place underground,” he says. “For everything you see on the surface, there’s more underneath.” Deep tunnels, often extending toward and beneath the enemy front lines, were used to monitor activity, reconnoiter for opportunities, and, sometimes, set off explosives before the other side did—a game of chicken to see who blew their tunnels first. Sometimes shallower tunnels were connected to create a transverse “apron tunnel,” the true front line of the battle, that could then be opened to become a new forward trench. This season, the team began using ground-penetrating radar in some portions of no-man’s-land to find more of these forward tunnels, some of which might not appear on any battlefield map.

As McGibbon approaches a tunnel opening that looks like a staved-in sinkhole, he explains how they have learned to distinguish between the remains of trenches and collapsed tunnels. Where trenches zigzag, tunnels tend to be straight. And while slumped trenches tend to have flat floors, tunnels cave in irregularly, leaving an undulating pattern on the modern ground surface.

In addition to documenting trenches and tunnels, the team also collects any surviving surface artifacts. They have found Allied and German barbed wire (on their respective sides of the line of control), a wide variety of munitions (from huge warship shells to bullets labeled in Arabic to mechanisms from shells timed to burst above ground), and the usual detritus of prolonged modern conflict, such as food canisters, rum ration flagons, buttons, fuel containers, canteens with bullet holes, and all manner of shrapnel. Such material is not unusual in Gallipoli—it can be seen everywhere, from museums to seafood restaurants—but those finds come without context. The true prize of this archaeological expedition is its maps.

Landscape archaeologist Jessie Birkett-Rees of La Trobe University in Melbourne pulls up, on a laptop, an image from the 1916 Şevki Paşa map. She then superimposes atop it the team’s mapped tunnels and trenches, a collection of squiggly lines and dots. Though it can be hard to follow, patterns soon become apparent. The ANZAC trenches, with their recursive system of long line trenches, intersecting communication trenches, and tunnels, are systematic. The Turkish lines, however, are more crenellated, complex, and labyrinthine. Each line is studded with dots representing artifacts and other features. “When you can lay your hands on information easily, that’s when it makes sense and becomes coherent,” says Sagona. The map also reflects several of the team’s finds that are beginning to reveal more about life in the trenches.

Back at Quinn’s Post, McGibbon once again charges into the roadside brush. Here, on the ANZAC side, the archaeologists found the remains of Malone Terrace, a series of terraced cuts in the hillside that Lieutenant Colonel William George Malone, a New Zealander, had constructed as a secure staging area for quick access to the front lines. It was thought that these heavily overgrown terraces were lost to erosion, but several levels have now been found, and mapping and artifact collection will continue here next season.

Almost directly opposite the terrace, on the other side of no-man’s-land, at a location known as the German Officers’ Trench (Merkez Tepe, to the Ottomans), the team found brick remains of a battlefield oven. In general, there are fewer artifacts on the Ottoman side of the battlefield, compared with the countless food containers on the Allied side, in large part because the Ottoman soldiers did not have to bid a hasty retreat. Together, these finds suggest that where the Allied soldiers ate tinned food, at least some of the Ottoman forces had access to bread—sometimes fresh and hot. This find comes from one of the battlefield’s tightest points, so one can imagine that the scent of baking flatbread might have wafted over to hungry ANZACs.

The history and archaeology of Gallipoli doesn’t begin and end in 1915. Indeed, older artifacts have been reported from around the battlefield, including a late Roman site uncovered during construction of the cemetery at Lone Pine in 1924. One sergeant reported that he found sarcophagi nearby during the battle itself. French troops to the south at Helles even conducted an archaeological excavation—also during the battle. George Augustus Auden, father of W.H. Auden, found a sarcophagus and two Greek inscriptions, and helped identify the Greek city of Alopekonnesos during an August offensive to the north. And the specter of Troy looms large over the area, as it did even when the offensive was being planned. To many on both sides, the Gallipoli Campaign seemed to share a spiritual kinship with the events of the Iliad.

“From the very beginning there’s a mythologization of the campaign, right from the first correspondence,” says Sarah Midford, a member of the survey team from the University of Melbourne who is studying the modern mythic narratives associated with Gallipoli in Australia. Many of the British involved in the battle had had some classical education, so a new battle near Troy inspired much romance about a “new Trojan War.” In The Anzac Book, a compilation of poems, stories, and illustrations from soldiers on the front lines, an Australian soldier wrote, “In honour to plain Private Bill / Great Agamemnon lifts his hand!”

“In terms of mythology, this campaign means so much to the Australian people,” Midford says. “They had almost prewritten the myth.” Australia, Midford explains, was then a country ready for war and sacrifice to cement its national character as separate from that of Britain. Losing at Gallipoli, but acquitting themselves well in a European theater was, Midford says, when a unified, distinct Australian sense of self emerged. And Anzac Day remains the most important day of remembrance in Australia. “This, in effect, is our blood spilt, this is the bit we can rally around,” she says. “There’s more pathos in a scar.” The same is true, but to a lesser extent, for New Zealand, says McGibbon.

One would imagine that Turkey would long ago have claimed this victory as a key formative experience for a modern country that was soon to form from the waning Ottoman Empire. According to A. Candan Kirişci, a scholar who studied representations of Gallipoli in Turkish literature at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, there are fewer personal narratives from the Turkish side than from the ANZAC side. But the battle was used in literature and wartime propaganda. After the loss of the war, the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and the emergence of modern Turkey, Gallipoli began to be treated both as a significant victory and, says Kirişci, “a fateful moment that brought together a great nation with its natural leader,” Atatürk. Interest in the battle has continued to increase as the centennial approaches, spurred in part by the ongoing presence of Australian and New Zealander visitors. New books, movies, and documentaries about Gallipoli have proliferated. “These new works continue to reinforce the official mythology that has developed around Gallipoli since the time of the actual battles,” says Kirişci. Indeed, at the recently opened Çanakkale Destanı Tanıtım Merkezi (“Dardanelles Epic Information Center”) at the base of Second Ridge Road, moving platforms, 3-D glasses, and wide-screen movies cast the battle in terms of martyrdom foundational to modern Turkey’s prosperity.

All of these mythic narratives seem, at first glance, ill-fitting to the reality of the battle, a slog over undistinguished scrubland, ill-conceived from the start. Though the Ottomans won, they gave more lives than the Allies and their victory was swamped by the losses that decided the war. But those mythologies weren’t born in histories, they were earned in tunnels. When you step onto the battlefield at Gallipoli, the leap from the grinding drudgery of trench warfare to epic national mythos doesn’t seem so large.