UPDATE (February 4, 2013): This story from ARCHAEOLOGY's January/February 2013 issue discusses the excavation of a site known as Greyfriars, under a Liecester parking lot, and the possibility that skeletal remains found there are those of King Richard III. DNA evidence, which was being analyzed at press time, has now confirmed that the bones are in fact those of the former King of England.

Pity poor Richard. Last of the House of York, last king of the Plantagenet line, last English monarch to die in battle. Richard III (r. 1483–1485) carries the most damning of reputations. His image as a villain—deformed of body and twisted of mind—has been firmly established, first by historians loyal to his successors (the Tudors), and later in literature and on the stage and screen. He is known to have seized the throne from his young nephews after the death of his brother, and it is rumored that he even had them killed. Thomas More, the Tudor historian, described him as “ill featured of limes, croke backed, his left shoulder much higher then his right.” Later, a century after his death, Shakespeare gave him few redeeming qualities, and this to say of himself: “And thus I clothe my naked villainy / With odd old ends, stol’n out of holy writ / And seem a saint, when most I play the devil.”

A reputation so bad practically begs for a reevaluation. Five hundred years after his death, Richard III finally seems to have passionate defenders and a good press team. Philippa Langely is a screenwriter and member of the Richard III Society, a group dedicated to rehabbing the king’s shabby image. To that end, she spent several years raising funds for the excavation of a parking lot in Leicester thought to have been the site of Greyfriars, the long-demolished friary where Richard III was supposedly buried. University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) was commissioned for the dig, and the field evaluation and excavations took place in September 2012.

In rapid succession, archaeologists found a trail of clues to what may be one of the more significant discoveries in English archaeology: the remains of a notorious, anointed King of England. The finds—punctuated by a dramatic series of press releases—attracted worldwide notice. “I found the project an interesting one, if I’m honest, because of the opportunity to learn more about the site of the Franciscan friary in which Richard III was said to have been buried, rather than actually finding the remains of the king, which I thought was a long shot,” says Richard Buckley, director of ULAS. “Of course finding Richard III would be the icing on the cake, but given that we had no reliable information about the layout of the friary buildings, let alone the position of the church, and a very restricted area available for trenching, it did not look likely.”

Even before anything was found, the excavation drew enormous public and media interest, leading the University of Leicester, the Leicester City Council, and the Richard III Society to keep the press and public apprised almost daily—an atypical practice in a field in which time, research, and analysis are often needed to understand finds. “It was unusual to be watched so closely by the press—I never expected there to be so much interest and was completely taken by surprise by the numbers of journalists who appeared on-site on the launch day,” says Buckley, who has excavated in the city for 30 years. “In some ways, this is what drove the strategy for regular updates as the work proceeded.”

For those who follow archaeological discoveries, the finds came with breathless speed. On September 5, archaeologists reported they had found traces of the friary church, including a tiled floor, walls, and architectural fragments. Then, on September 7, they reported finding fragments of window tracery thought to be from the church, as well as paving stones from a garden that occupied the area after the friary had been demolished in the 1530s. In 1612, this garden was reported to have held a stone pillar that identified it as the burial place of Richard III.

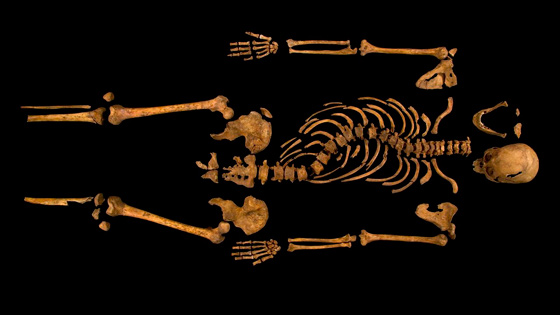

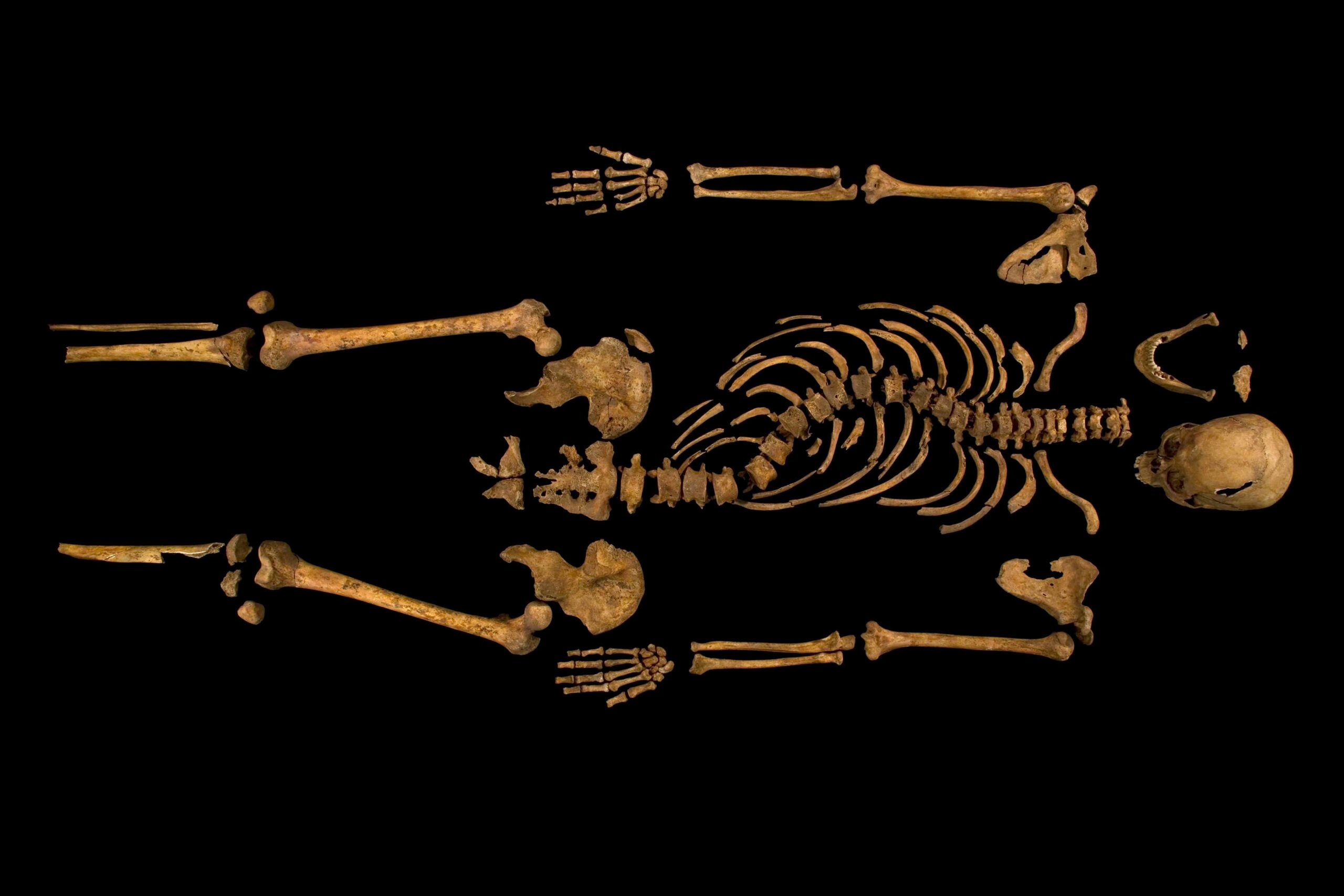

And then, on September 11, came news that they had found human remains. These were uncovered in what is thought to have been the choir, the specific part of the friary church where Richard III was said to have been buried. The skeleton is that of an adult male with scoliosis—a spinal deformity consistent with historical accounts of the king’s physical state. And, perhaps most tellingly, the remains exhibit battle wounds, including a puncture on the top of the head, the cleaving of the rear part of the skull, and a small piece of iron embedded in the spine. Richard III died in the Battle of Bosworth Field as he fought forces aligned with Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII. The case—at this stage still circumstantial—for these remains being those of Richard III is hard to ignore.

Confirmation of the remains as Richard III’s will have to wait for the results of mitochondrial DNA tests comparing the skeleton’s genetic material with that of Michael Ibsen, a Canadian who is a seventeenth great-grand-nephew of the king. The results are likely to be announced in conjunction with a television special produced alongside the excavation. ULAS’s seasoned archaeological team has very clearly stated that the discovery of Richard III’s remains has always been more a hope than an expectation. They accept the risk that the early press coverage will prove to be only hype if the remains are shown not to be the king’s. “I think the public enjoy the detective-story element of archaeology, in particular the process of floating ideas and interpretations, some of which can then be tested by more detailed scientific analysis,” says Buckley. “There were no real drawbacks [to involving the public in this way] and it was immensely rewarding to have so much interest in our work—great for the archaeology of Leicester and also for the discipline in general.”

Further analysis of the skeleton will include radiocarbon dating and bone analysis to learn about its pathology, diet, age, stature, and origins. If it is indeed shown to be Richard III’s, Langley says the work might help provide specifics on the king’s physical condition, his death at Bosworth Field, and how his body was treated before burial. A realistic picture of the man, she says, might help dispel some of the myths—in particular the oft-told tale that his remains were exhumed and scattered in the River Soar during the Reformation.

The manner in which the finds were reported certainly raised a few eyebrows. But according to Richard Hodges, archaeologist and president of the American University of Rome, who has worked with Buckley before, the archaeology behind the press releases can be trusted to root out the truth—as well as attract a little positivity. “I should be far from certain that Richard III will be found,” says Hodges, “but U.K. archaeology has gained a great deal of valuable attention at a time of austerity!”

The Twenty-First Century Autopsy of Richard III

King Richard III of England was killed in August 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field, the clash that ended the War of the Roses. He was thought to have been buried beneath Greyfriars, a now demolished monastery in Leicester, England. Last year, archaeologists recovered a skeleton from the site that dated to the correct time period and exhibited scoliosis, a curvature of the spine known to afflict Richard. DNA analysis has now confirmed that the bones belong to the long dead monarch. These images of his bones open a window into the life and grisly death of the last English king to die in combat.—Eric A. Powell