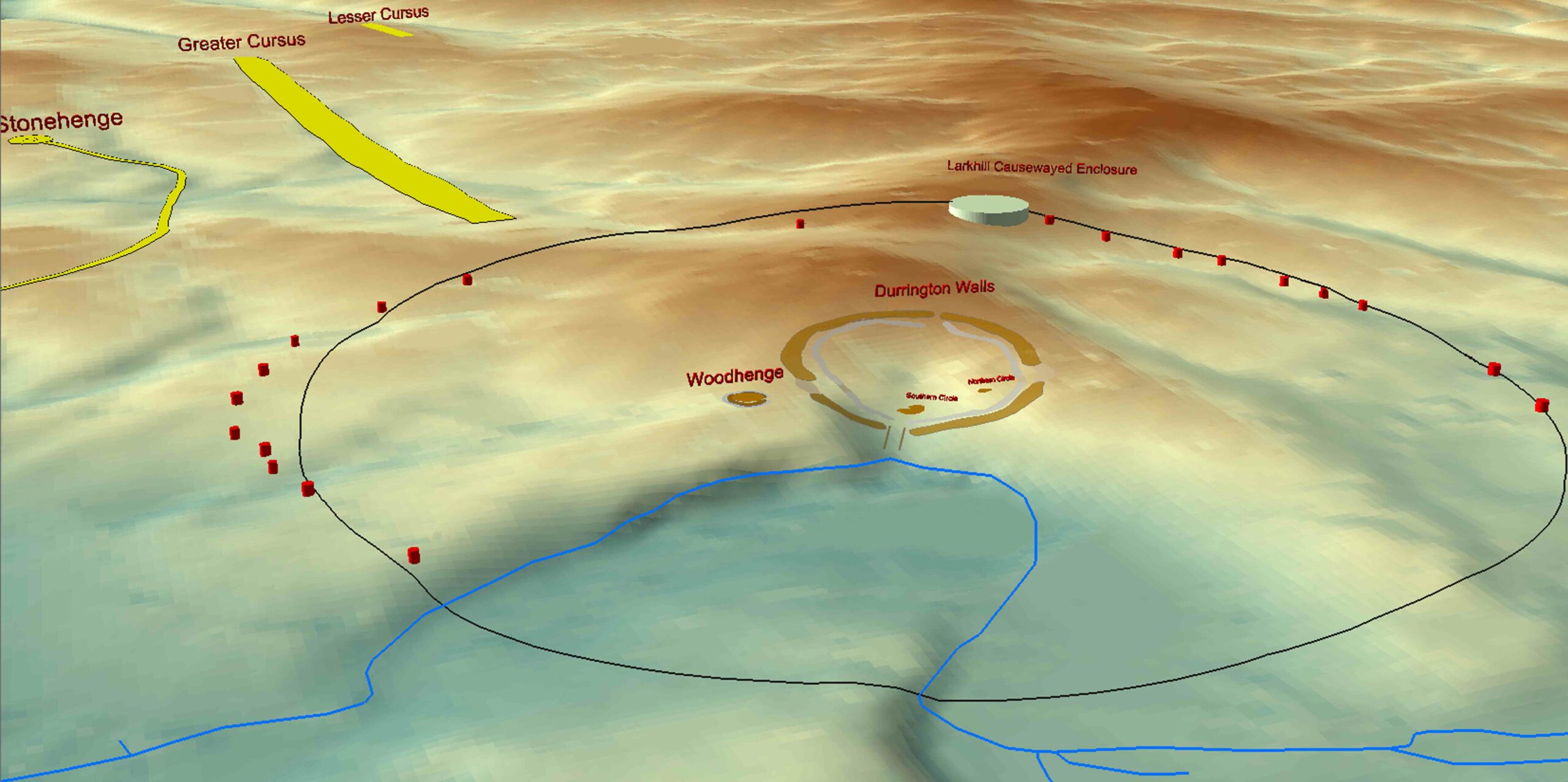

As if Stonehenge weren’t spectacular enough, an unprecedented digital survey—involving aerial laser scanning, ground-penetrating radar, and other geophysical and remote-sensing technologies—has revealed that the iconic 5,000-year-old standing stones were part of a much broader Neolithic ceremonial landscape. Unveiled at the British Science Festival in September, the research has revealed 17 new monuments and thousands of as-yet-uninterpreted archaeological features, including small shrines, burial mounds, and massive pits, across nearly five square miles of the Salisbury Plain.

The research is also providing new insights into already documented features. For example, geophysical surveying of the “Cursus”—a two-mile-long mound north of Stonehenge—identified two massive pits that align astronomically with Stonehenge, in addition to a series of gaps in the mound. “The pits show how the Cursus, which was constructed 400 years earlier than Stonehenge, influenced the placement of the standing stones,” explains Vincent Gaffney of the University of Bradford. “We think that the gaps in the Cursus would have guided the movement of people as they processed to Stonehenge, contradicting the [previous] thinking that few people approached the standing stones.” Further, remote sensing at Durrington Walls—a mile-wide ritual monument close to Stonehenge—revealed that it used to be associated with up to 60 huge standing stones, some of which may now lie under earthen banks. “In the past we had this idea that Stonehenge was standing in splendid isolation, but it wasn’t,” says Gaffney. “It’s absolutely huge.”