In the attack, 75 percent of the U.S. planes sitting at airfields near Pearl Harbor were damaged or destroyed. For all the aircraft lost—the Japanese lost 59—there is one that can be linked to that morning. Very few people can gain access to it, and even then only with a military escort, since it lies in the water just off Marine Corps Base Hawaii at Kaneohe Bay, on the east side of Oahu. During the war, this was the location of a Naval Air Station for PBY-5 Catalina seaplanes, long-range reconnaissance craft.

The Japanese knew that these planes could track them to their carriers north of the island. The PBY-5s had a range of almost 1,500 miles and could be in the air in minutes. So, just before the general attack, at 7:48 a.m., attacking planes strafed the Naval Air Station with 20 mm incendiary rounds and bombs. Of the 36 planes there, three were out on patrol, six were damaged, and the rest were destroyed. Servicemen at Kaneohe Bay scrambled to put out fires and salvage what they could.

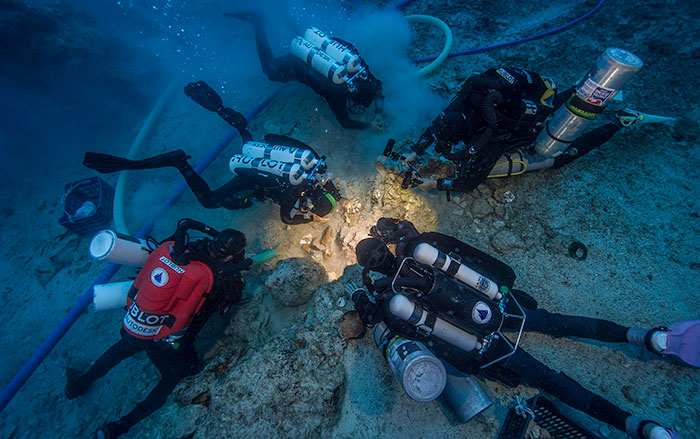

In the 1980s, the mooring area was used for training mine-detecting dolphins. That could be when the battered wreck of one of the PBY-5s was first identified. In 1994, students and archaeologists from the University of Hawaii and East Carolina University surveyed the remains. “It was a good start on the submerged story,” says Hans Van Tilburg, who was on that team and is now a maritime heritage coordinator with NOAA. In 2000, the University of Hawaii returned to the site for surveys that turned up aviation-related scraps, but no other planes. It’s possible that the others had been salvaged or drifted into deeper, murkier water. “Our desire is to get back to the bay and continue looking in deeper water,” says Van Tilburg.

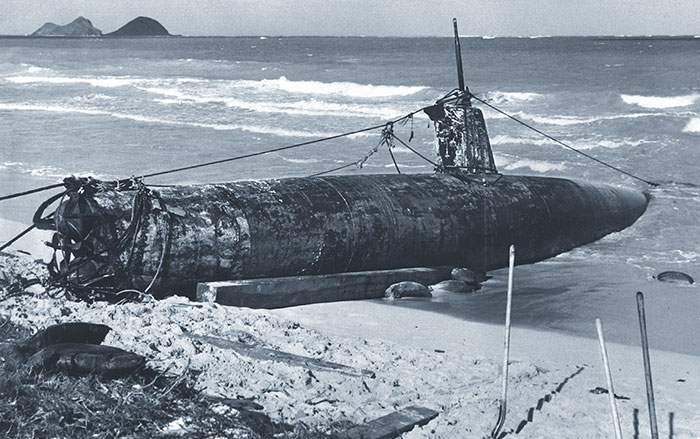

The remains of the plane consist of the forward portion of its fuselage, including the cockpit and turret, which lies on its starboard side in about 30 feet of water, the starboard half of the 105-foot parasol wing, and the fragmented remains of the tail 30 feet away. It is likely that fuel tanks in the center of the wing exploded, but the wrecked seaplane holds telling details about the frantic eight minutes of that initial Japanese attack.

There is a large gash in the port side, just where a propeller would have been. Inside the cockpit, the port throttle is in the forward position. Yet the plane is still attached to its mooring line. This all suggests that an attempt was made to scramble at least one of the planes—but that it didn’t get far. The wreck does not provide evidence of what happened to the pilot, or just how many planes were moored at Kaneohe that morning. Some sources say three, others four, and there are six in a drawing by a Japanese pilot. “Every eyewitness account contradicts the other accounts,” says Van Tilburg. “It’s still a bit of a mystery. But this might be the only plane we know of that we can point to and say, ‘This is a December 7 casualty.’”