University of Michigan archaeologist John O’Shea was reading a book, some 10 years ago, about modern-day reindeer herders living in the Subarctic and some of the elaborate stone structures they use to manage their animals—usually called caribou in North America. O’Shea studies not only prehistoric cultures, but also nineteenth-century shipwrecks in the Great Lakes. That’s why at around the same time he was reading up on human interactions with reindeer, he was also examining new underwater topographical maps of Lake Huron. Those charts showed that a rocky underwater feature known as Six Mile Shoal was actually a continuous underwater ridge stretching 112 miles from northeastern Michigan to southern Ontario.

As O’Shea looked at the map and envisioned what this ridge might have looked like in the past, he realized that around the end of the last Ice Age, some 9,900 years ago, it would not have been submerged. Rather, it would have been a land bridge, with icy lakes on either side and the receding glacial ice sheet just a few hundred miles to the north. The ridge would probably have remained much colder than the mainland, offering a refuge in a slowly warming world for animals and vegetation adapted to very cold environments. Such isolated pockets of archaic ecosystems that endure after broad continent-wide climate shifts are known as refugia. O’Shea believed that during the end of the Ice Age, this land bridge could have been just such a refugium, preserving the frigid ecosystem that caribou thrive in even while the glacial ice sheet was in retreat. “It all came together for me—the fact that there was this geologic feature that would have been dry land 9,900 years ago that would still have had reindeer,” says O’Shea. And if herds of caribou had once migrated across this landscape, he reasoned, there were probably people hunting them. “I thought we could find signs of those hunters.”

Archaeologists have long suspected that since the Upper Midwest would have been an area attractive to these herds, the region’s prehistoric Ice Age inhabitants, known as Paleoindians, would have relied heavily on them. But evidence for this way of life has been scant.

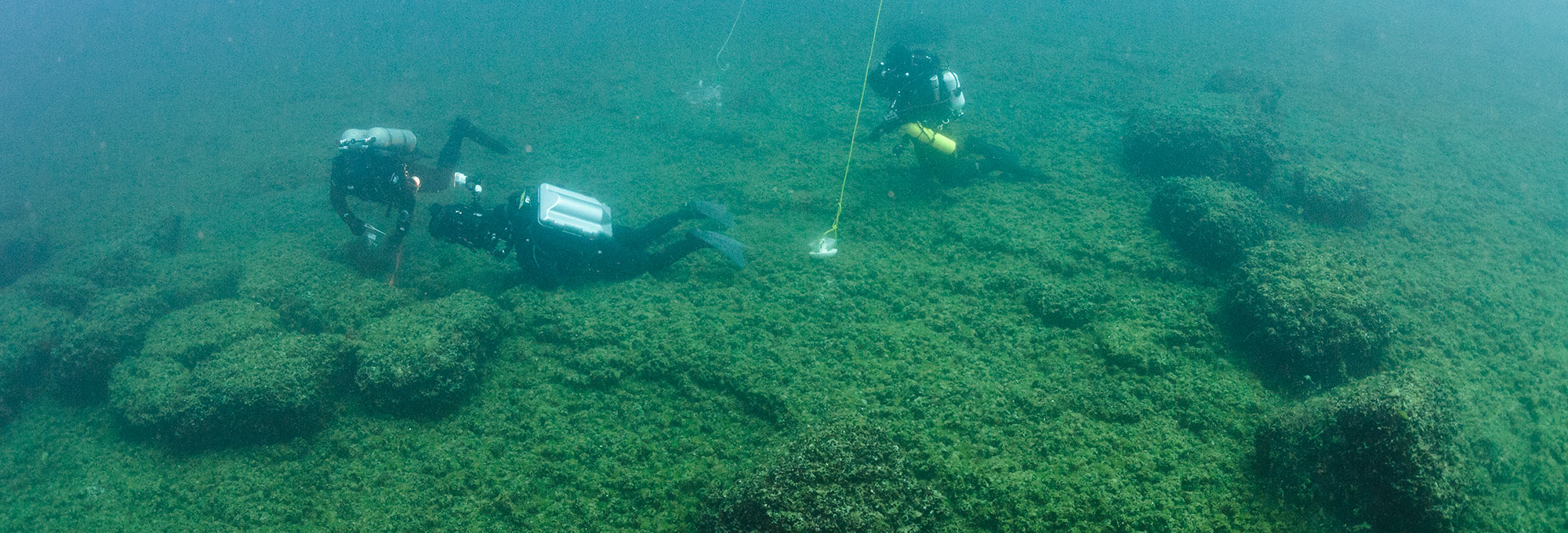

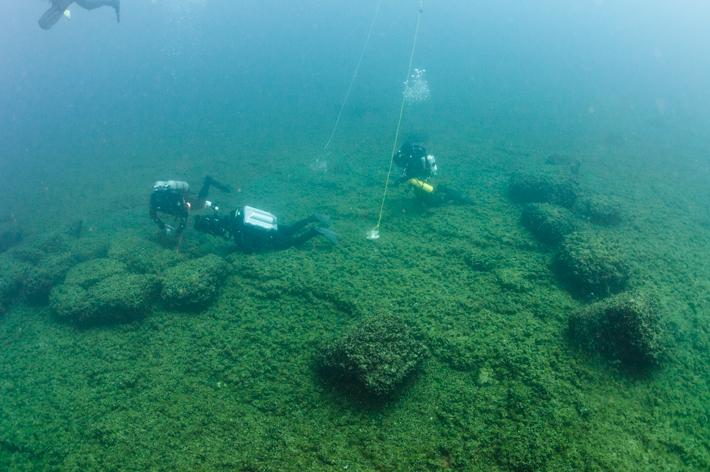

Acidic soils around the Great Lakes break down bones quickly, making it difficult to find the remains of caribou—or of any ancient animal—in the region. Any stone hunting structures that may have existed were likely either knocked down by later settlers or are impossible to distinguish from walls and rock piles created by modern inhabitants. O’Shea thought that the ridge sitting beneath the waters of Lake Huron, now known as the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, could have acted as a time capsule. Though the lake is notoriously unpredictable and rough on the surface, its cold lower reaches are surprisingly calm, with gentle currents and 100 feet of visibility. O’Shea thought that some of the hunting structures that were destroyed in other parts of the Midwest might still persist on the submerged ridge, along with campsites, tools, and other remnants of the caribou hunters.

The idea, O’Shea admits, was a little bit wacky, but he thought his reasoning was sound even if locating the remains of that caribou hunting culture posed a daunting challenge. It would mean scanning hundreds of square miles of lake bed, 60 miles offshore. The chances of finding something as small as a campsite or hunting blind below the surface seemed remote. Furthermore, researching the ridge was a logistical nightmare, and meant signing up scuba-diving archaeologists, ROV operators, and boat pilots. It also meant sending researchers down 120 to 130 feet below the surface, the limit for divers using scuba gear, a depth at which they can only remain for short periods. Expectations for the project at the outset were kept low.

That first field season in 2008 was grueling. On the few days when the weather cooperated enough to get out on the big lake, O’Shea and his team would make the 60-mile journey in a small boat from the city of Alpena’s port to the underwater ridge. There they identified three areas to scan, ranging from four to seven square miles. Day after day they followed a grid pattern, using side-scanning sonar to get an overview of the ridge, creating a map of the land below. This systematic approach paid off, and they were able to identify ancient shorelines, prehistoric rivers, lakes, and bogs. O’Shea hoped they could use that preliminary data to pinpoint possible areas for investigation during a second field season. But then, something unexpected happened. During one pass, a bright line of rocks stood out. The team sent an ROV down and found, to their surprise, that it was a man-made drive lane, a long stone alignment used to herd caribou into a corral, and a hunting blind where Paleoindians would have waited to kill the animals. “It was just dumb luck,” says O’Shea. If the boat had been traveling at even a slightly different angle, the team would have missed the drive lane.

Since then, over almost a decade of field seasons, O’Shea’s team has identified more than 60 drive lanes and hunting blinds, as well as structures that were possibly caribou meat caches, all across the Alpena-Amberley Ridge. One reason they have found so many archaeological sites intact is that, although the ridge’s original layer of thin topsoil has washed away, no new sediment covered it, leaving a perfectly preserved record of the people who lived there. “That’s what’s nice about our research site,” says O’Shea. “There’s only a 2,000-year window where it was dry land. Then it was submerged and didn’t reemerge again.” Dating of the remains of ancient trees on the ridge based on wood samples and ancient pollen has shown that the land bridge would have indeed been a subarctic environment, says University of Texas at Arlington archaeologist Ashley Lemke, who has worked on the project for six seasons. She points out that while they moved across the ridge, Paleoindians would have encountered a rocky landscape with thin soils, covered in bogs and marshes. While the landscapes on the mainland were slowly developing into the grassland, savannah, and forest ecosystems that exist there today, the land bridge was covered in sparse clumps of trees such as spruce, tamarack, and aspen. “It was an Ice Age–like environment,” says Lemke. “That’s why caribou would be there. This is a place where the Ice Age lasted a little longer.”

During the winter months, the ridge would have been brutally cold, leading O’Shea and his team to believe that the Paleoindians would not have lived there year-round. In the autumn, when caribou herds were healthiest, with the best meat and hides, O’Shea believes small family groups would camp on the land bridge as the animals migrated across it toward the southeast. The families would hunt in small groups, processing hides and drying and storing the meat in stone caches on the ridge for the winter. Because the cold winters froze the lake solid, O’Shea believes the caribou hunters would have been able to travel over the ice to the ridge in the winter and collect meat when they needed to.

In the spring, as the herds of caribou headed up the ridge to the northwest, the hunters would have engaged in a different style of hunting, working in larger groups to herd the caribou down through stone drive lanes and processing large amounts of meat. “Spring is the direst time in northern climates,” says O’Shea, who notes that after enduring a harsh winter, the undernourished Paleoindians would have needed a way to get large amounts of meat quickly. “They used more complex hunting methods that took a lot of people to operate,” he says. “Then they would sit around for a couple of weeks eating caribou.”

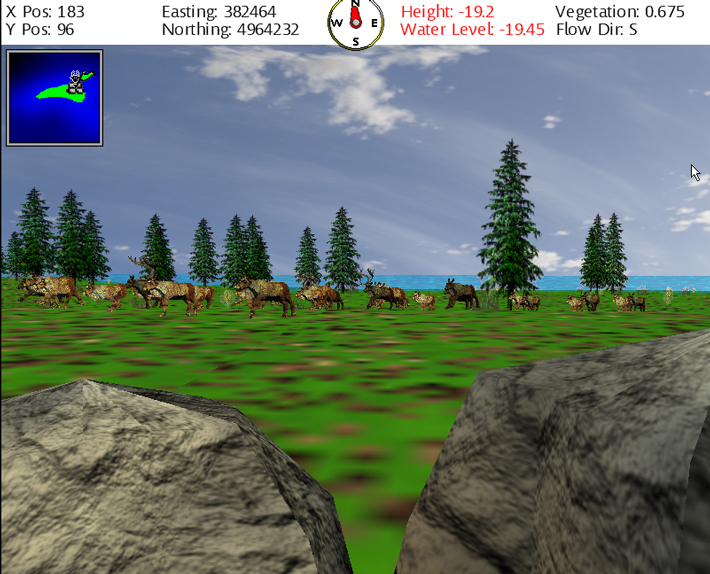

While the team has successfully located a number of sites and even excavated a handful of stone tools, O’Shea knew that surveying the entire ridge would take years of mind-numbing radar scanning and cost a lot of money. So he turned to computer scientist Robert Reynolds, director of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Wayne State University, for help in better understanding how the hunters might have exploited the land bridge and where still more sites might be located. “Initially the team was using their own intuition about the landscape to predict where they might locate sites,” says Reynolds. “They felt they reached a limit of their intuition and called us in to create a 3-D virtual model of the ridge.” By combining this virtual model of the refugium with information about caribou migratory behavior and ethnographic and archaeological data, Reynolds was able to simulate how caribou and hunters might both have used the landscape.

The model produced a list of hot spots on the ridge where the researchers should look for hunting structures. In 2015, O’Shea tested the predictions, exploring two sites that Reynolds had flagged, one of which produced a previously undiscovered hunting structure. The simulation also predicted where one of the drive lanes that had already been discovered would appear. Now O’Shea and Reynolds want to fine-tune the simulation to help them pinpoint the most likely location of campsites on the ridge. They are currently in talks with modern caribou hunters living in Alaska who may come down and use the simulator. The hope is that with their experience and traditional knowledge, the modern hunters can “walk” through the model of the ridge and point out likely spots for both hunting structures and family encampments, which can then be explored in future field seasons.

The team is also using other new technologies to search the ridge’s submerged Ice Age landscape for campsites, which have remained elusive. Last summer, they began testing an autonomous underwater vehicle that can travel much closer to the lake floor than tethered ROVs, which allows it to create even more detailed sonar imagery of the ridge than was previously possible. “If our model is right and the fall hunting is done in small family groups, my expectation is we should have lots of little campsites cycling over the years,” says O’Shea. “We should see a lot of them.”

Lemke, who is the primary ROV pilot for the team, explains that while the structures on the ridge were almost certainly built for hunting caribou, there is still scant evidence that the animals actually existed there—just one piece of burned caribou bone and a single tooth collected thus far. This can be explained by the fact that the hunting structures they’ve been able to study, she says, would have been kept meticulously clean of bone and animal debris, since the scent of blood would scare off other caribou. Butchering and processing the animals would have taken place at other sites or at the camps where the hunters lived. These should be full of bones and evidence of the presence of caribou. “We’ve gotten good at finding out where they were hunting,” says Lemke. “Now we’re curious where they were living.”

The technology upgrades have already yielded results. While watching video collected from an ROV exploring a drive-lane site called Drop 45, O’Shea noticed two stone circles, similar to tepee rings found in the western United States. A preliminary excavation found remnants of a fire hearth in the middle of the ring, a good indication that this was one of the long-sought habitation sites. The stone circles will be a major focus next season. O’Shea also hopes to begin using a three-person submersible in 2018 that can stay underwater for up to eight hours at a time, greatly increasing the team’s ability to survey the site. It will also allow the researchers to investigate the bottom of a 500-foot-deep cliff edge they have not been able to explore so far.

All this work is helping complete a picture of an Ice Age landscape that sustained caribou and caribou hunters alike for two millennia. It disappeared under the waves of Lake Huron some 8,000 years ago, wholly forgotten until O’Shea’s unusually broad reading habits led him to discover it. “It was serendipity,” says O’Shea. “But the fact that we found the hunting structures isn’t shocking to me. It’s thinking like a scientist. Science has a creative component that is, or should be, present at the beginning of every research question.”

A number of other questions remain. For example, O’Shea says he’s not yet sure if the hunters stayed out on the ridge during the summer to fish, or if they returned to camps on the mainland. One of the projects the team is working on when Huron is too rough for underwater exploration—which it often is—is excavating sites on mainland Michigan that may have been occupied by the caribou hunters during summer and winter months, when they were not hunting on the ridge. “We’ve come up with two candidate sites with tool assemblages in the same date range,” says O’Shea. “We want to tie all the pieces of their system together to see how they operated.” He suggests that relying on an isolated Ice Age landscape for their way of life must have made the caribou hunters fundamentally different from their contemporaries. “We want to know just how different they were.”