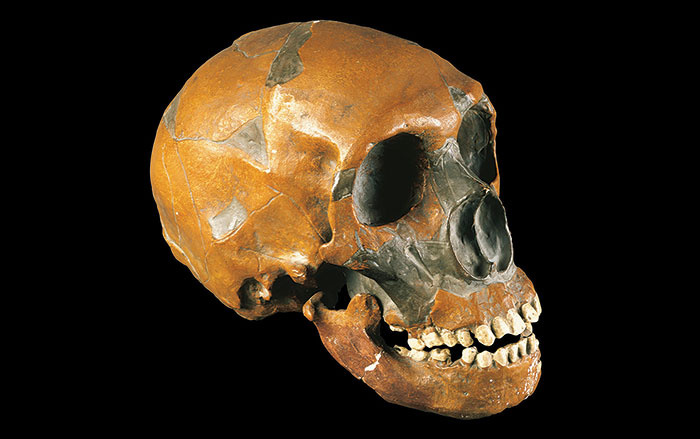

Genetic testing of a single, 90,000-year-old sliver of bone from an approximately 13-year-old girl has confirmed something researchers had long suspected: It has provided clear evidence of interbreeding between two distinct groups of early humans.

Earlier analysis of the girl’s mitochondrial DNA had shown that her mother was of Neanderthal ancestry. The new research, led by paleogeneticists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, examined her entire genome. They then compared it to previously sequenced paleogenomes, including those of other ancient humans. The results were unambiguous—the girl’s DNA matched Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes to an equal degree. She had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Denisovans were a type of early hominin named after the cave in the Altai Mountains of present-day Russia where their remains were found around a decade ago. “When I first saw the combined Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry, I got worried that I had made a mistake in the lab, and that this was somehow a mix-up of two different bones,” says Max Planck’s Viviane Slon. “It was only after repeating the experiments several times, and consistently seeing the same result, that I convinced myself—and my colleagues—that the girl’s mixed ancestry was real.”

The team’s finding of a direct offspring of a Neanderthal and a Denisovan implies that individuals from the two groups mixed when they had the opportunity to meet. “Taken together with evidence that Neanderthals and Denisovans also mixed with ancient modern humans,” says Slon, “this suggests that different groups of humans have always mixed when encountering each other.”