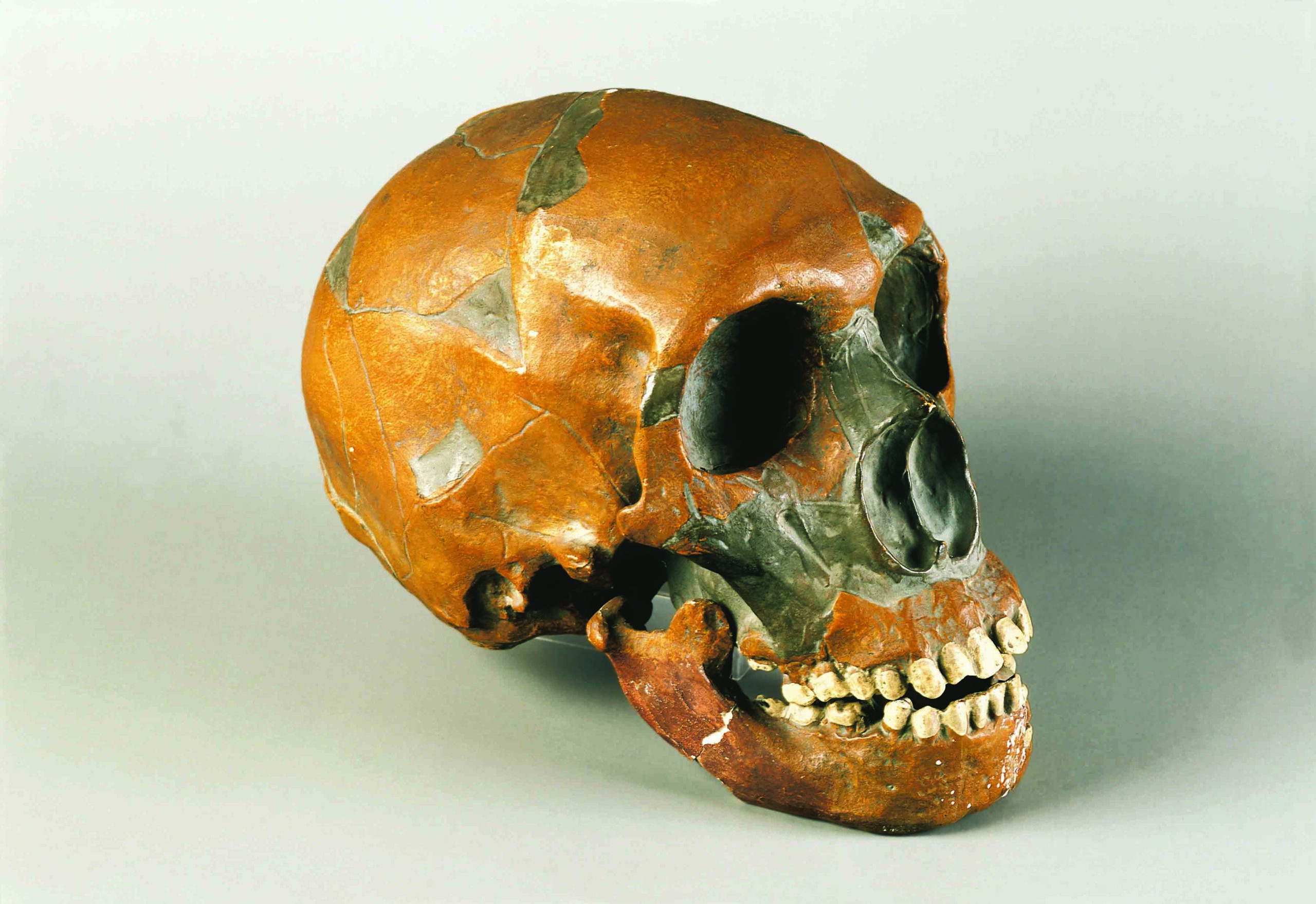

Neanderthals—Homo sapiens’ closest cousins—went extinct around 30,000 years ago. Yet some people possess genetic markers inherited from these distant relatives. This was the conclusion of a groundbreaking 2010 study led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute, whose team successfully sequenced a Neanderthal genome for the first time. Around 400,000 years ago, Neanderthals diverged from the primate line that would go on to produce Homo sapiens, and spread to parts of Europe and western Asia. After modern humans migrated out of Africa, researchers believe they encountered and interbred with Neanderthals in the Middle East around 60,000 years ago. As a result, modern humans of non-African descent share around 2 percent of their DNA with Neanderthals. Scientists are still learning how these genes manifest themselves. “Neanderthals contributed DNA to present-day people,” says Pääbo, “and this has physiological effects today, for example in immune defense, pain sensitivity, risk for miscarriages, and susceptibility to severe outcomes from COVID-19.”