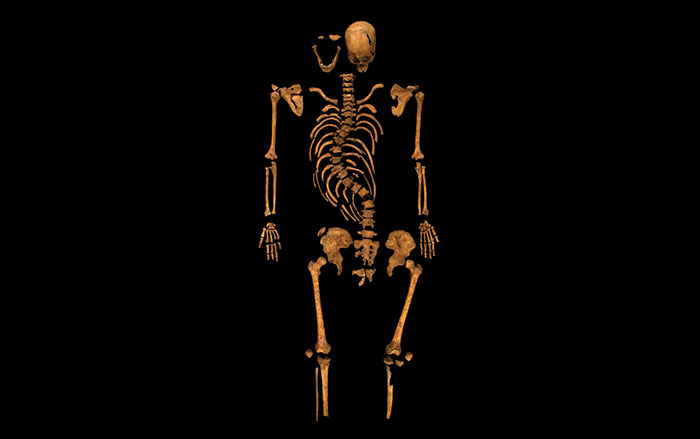

The largest-ever study of Viking DNA has revealed a wealth of information, offering new insights into the Vikings’ genetic diversity and travel habits. The ambitious research analyzed DNA taken from 442 skeletons discovered at more than 80 Viking sites across northern Europe and Greenland. The genomes were then compared with a genetic database of thousands of present-day individuals to try to ascertain who the Vikings really were and where they ventured. One of the project’s primary objectives was to better understand the Viking diaspora, says University of California, Berkeley, geneticist Rasmus Nielsen.

It turns out that the roving bands of raiders and traders, traditionally thought to have come only from Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, were far more genetically diverse than expected. According to Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen, one of the most unexpected results was that the Viking Age of exploration may have actually been driven by outsiders. The researchers found that just prior to the Viking Age and during its height, between A.D. 800 and 1050, genes flowed into Scandinavia from people arriving there from eastern and southern Europe, and even from western Asia. In contrast to the traditional image of the light-haired, light-eyed Viking, the genetic evidence shows that dark hair and eyes were far more common among Scandinavians of the Viking Age than they are today. “Vikings were not restricted to genetically pure Scandinavians,” says Willerslev, “but were a diverse group of peoples with diverse ancestry.” In fact, some who adopted the trappings of Viking identity were not Scandinavian at all. For example, two individuals who were buried in Scotland’s Orkney Islands with Viking grave goods and in traditional Viking style were, surprisingly, determined to be genetically linked to the Picts of Scotland and contemporaneous inhabitants of Ireland.

Viking raiding parties departing from a given country, the study found, tended to journey consistently to a particular destination. Expeditions from Sweden usually went eastward to the Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine; Vikings from Norway tended to sail to Iceland, Greenland, and Ireland; and those from Denmark predominantly ventured to England. The study also determined that Viking expeditions sometimes comprised a group of close-knit, even related, individuals. Analysis of 41 skeletons from two ship burials in Salme, Estonia, indicates that they likely hailed from a small village in Sweden, and that four were brothers, entombed alongside one another. (To read a full-length article about Salme, go to “The First Vikings.”)