The sprawling, vine-tangled rainforests of today’s Yucatán Peninsula were once home to a densely settled patchwork of rival Maya kingdoms. Between A.D. 150 and 900, known as the Classic period, these dynasties jostled for power, which was seized through raids, battles, and assassinations, and marked by grand monuments and celebrated with extravagant ceremonies. Members of royal families memorialized their feats by carving limestone stelas with pictorial scenes and hieroglyphic inscriptions, many of which depict two bloodlines that each attained near-supremacy over the Maya world at varying points. These two lineages, known as the Kaanul Dynasty and the lords of Tikal, battled throughout the whole of the Classic period. As the power of one family waxed, the might of the other waned.

Toward the end of the seventh century A.D., gamblers or pundits might have done best to place their bets on the Kaanul, or Snake, Dynasty, which ruled from the great city of Calakmul in present-day Mexico. “Through its own industry and machinations, and probably military success, the Kaanul Dynasty got the upper hand of many other kingdoms for about 130 years,” says Simon Martin, an epigrapher at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Powerful Kaanul kings, including Yuknoom Ch’een II (reigned A.D. 636–686) and his successor, extended the family’s influence over much of the lowland Maya world. Archaeologists can track the spread of this influence from inscriptions in which local lords declared their allegiance to Calakmul and from the Kaanul-style shrines and buildings constructed in cities subjugated by Kaanul kings. These cities were chosen strategically by the Snake kings to surround the capital of their nemeses at Tikal, a lineage with an as-yet-untranslated hieroglyphic emblem that depicts a feathered alligator or sometimes what appears to be tied reeds. Tikal is situated 60 miles south of Calakmul in what is now Guatemala.

Kaanul leaders recruited vassals through violence and perhaps economic pressure, but weddings also figured prominently in their statecraft. Throughout its heyday, the Snake Dynasty arranged strategic marriages between royal Kaanul women and lower-ranking men who ruled regions the Kaanul wanted to bring under their control. As these queens moved to the lands their husbands controlled and bore children, securing lines of succession, this system of alliances promised to endure for generations.

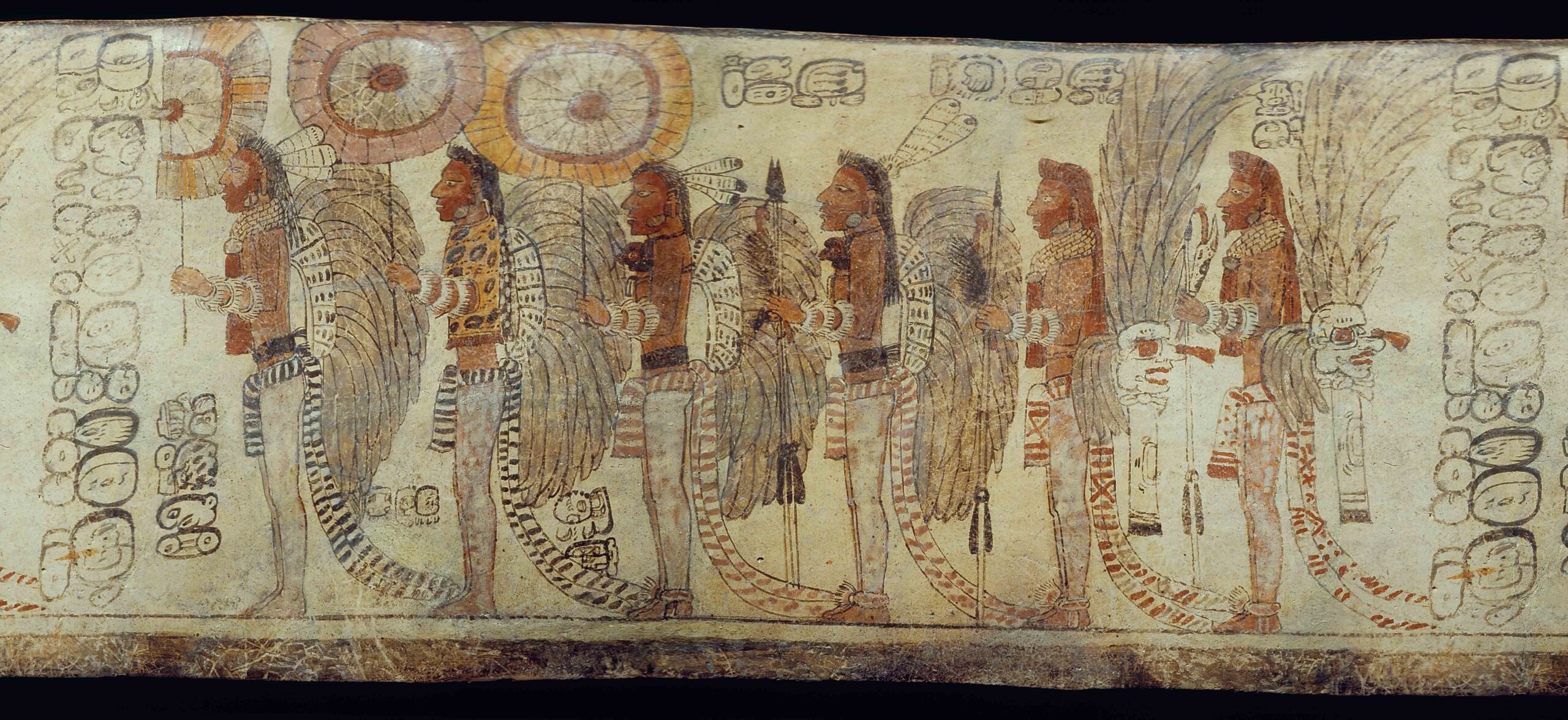

In their newly adopted homes, these Kaanul “stranger queens,” as University of Miami archaeologist Traci Ardren has called them, had certain obligations demanded by their sex and gender. These royal women were sorcerers, privy to arcane knowledge about rituals and calendar keeping. They divined the future and connected with spirits, perhaps to determine auspicious dates on which to invade a rival city. “We often see the women portrayed as openers of portals or as communicators with ancestors,” says Ardren. Above all, though, the queens were expected to be wives and mothers, producing the heirs needed to perpetuate dynastic bloodlines. “The investment of the state in their biological reproduction was huge,” says Ardren. “If the dynasty doesn’t continue, everything else falls apart.”

But once a stranger queen fulfilled the duties expected of her as a woman, she was able to assume privileges and powers that were typically restricted to men in Classic Maya society. These women dressed in masculine garb, waged wars, played power politics, and commissioned monuments touting their achievements. In Maya texts, scholars have identified around 35 women from a variety of ruling families who wed outside their dynastic group, yet the Kaanul seem to have prioritized and benefited from this strategy more than others. Indeed, two of the most powerful Maya women known, Lady K’abel and Lady Six Sky, were stranger queens in service of the Kaanul.

What researchers have learned about these women since the 1960s has come from hieroglyphic inscriptions and other hints in the archaeological record. In recent decades, Ardren and others have been able to supplement Lady K’abel’s and Lady Six Sky’s biographies by reexamining these texts and archaeological sites and artifacts. Their new research indicates that both women entered diplomatic marriages to boost the status of their bloodline and to support Calakmul in its seemingly eternal struggle against Tikal. As stranger queens, they helped curb Tikal’s rise, at least for a time. The research has shown that the women weren’t passive pawns in a game run by male family members. Rather, they seem to have been active players, ambitious and invested in their political careers. And while Lady K’abel and Lady Six Sky both started as stranger queens, they used their positions to forge distinctive legacies.

One of the power centers with which the Kaanul Dynasty most wanted to ally was Waka’, a strategically located city-state about 70 miles south of Calakmul and 45 miles west of Tikal. The ruins of Waka’, also called El Perú, were first documented archaeologically in the 1960s by Harvard University’s Ian Graham and have been investigated since 2003 by the El Perú-Waka’ Regional Archaeological Project. Thus far, the ongoing excavations and surveys have identified more than 1,200 structures across the site and its hinterlands, spread over an area of seven square miles. Sitting atop an escarpment, the city’s center featured palaces and plazas that overlooked scattered villages and rolling farmland. The Kaanul knew that, by virtue of its proximity to Tikal, Waka’ could be used to surveil the rival city or serve as a staging ground for invasions. Waka’ was also economically important, as it was situated near the confluence of two navigable rivers, the San Juan and the San Pedro Mártir, as well as along trade routes that linked the region’s highlands and lowlands.

For a few hundred years, starting in the late sixth century A.D., the rulers of Waka’ served as vassals of Kaanul. To gain and maintain influence, the Snake family embedded its princesses in Waka’ society. Based on inscriptions discovered at the site, researchers know that at least three Kaanul daughters became stranger queens in Waka’. Among the trio, the best known is Ix Kaloomte’ K’abel, or Lady K’abel, who wed the Waka’ ruler K’inich B’ahlam II, or Sun-Faced Jaguar (reigned A.D. 684–702) of the Wak, or Centipede, Dynasty.

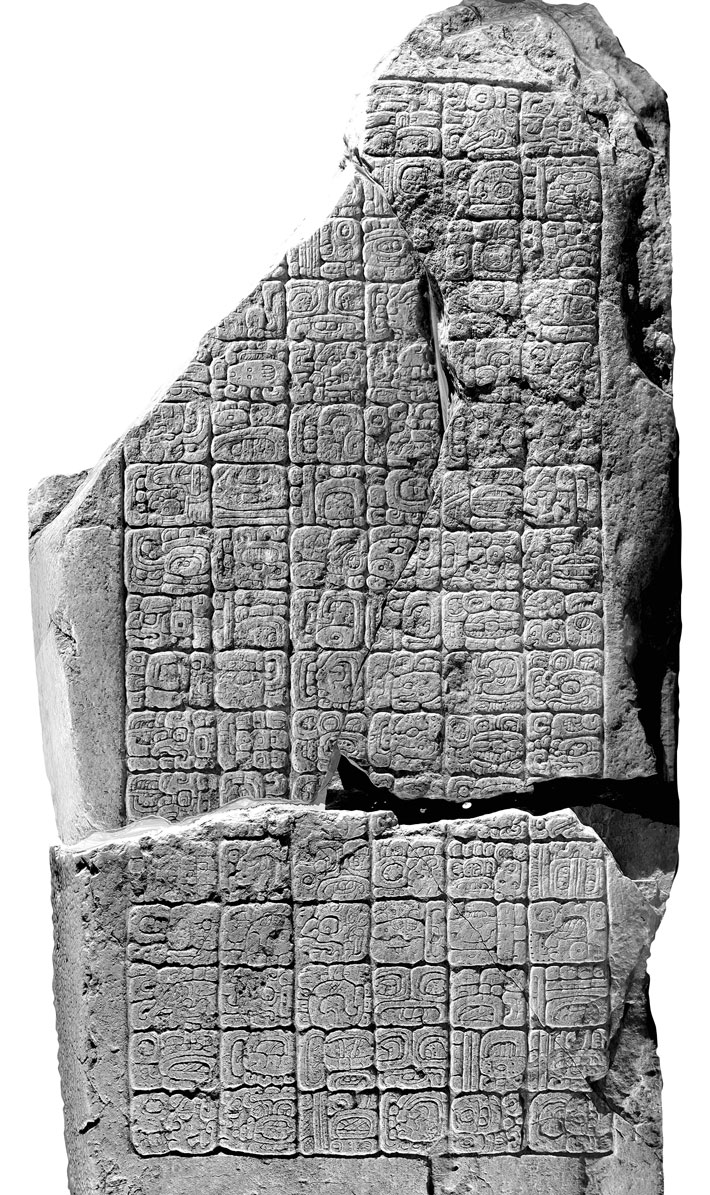

Lady K’abel’s life story began to resurface 60 years ago during Graham’s investigations at Waka’. He discovered the stumps of two sawn-off stelas that would have originally loomed over a plaza, but which he thought must have been destroyed by modern looters. Decades later, by studying published photographs of stelas housed in different museums, he identified two huge monuments as the stelas that had likely once stood side by side overlooking the plaza. One is a nine-foot-tall, 2,500-pound limestone stela now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, while its partner of similar scale is in the Kimbell Art Museum. Both stelas feature portraits as well as glyphs naming their respective subjects: Lady K’abel and her husband, K’inich B’ahlam II. The Cleveland stela depicts Lady K’abel as a warrior queen, gripping a scepter and shield, being served by an attendant half her size. She appears to wear a tunic strung with jade, a collar and belt in the form of deities’ faces, and a lofty headdress of quetzal feathers. Her husband’s stela shows the king in regalia adorned with water lilies, fish, and a snake deity, likely meant to symbolize his divine role in ensuring successful harvests.

The two monuments commemorate milestones in the couple’s union and reign—and make it clear that Lady K’abel married beneath her status. Inscriptions on her stela provide her pedigree as a Kaanul princess born to the powerful king Yuknoom Ch’een II. “She’s undeniably the daughter of the ruler of Calakmul, who is dominating the Snake Dynasty at its height, at the apex of its power,” says Olivia Navarro-Farr, an archaeologist at the College of Wooster who codirects the El Perú-Waka’ Regional Archaeological Project. Lady K’abel’s husband’s stela records that he submitted to the oversight of her father, the king of Calakmul. By establishing Lady K’abel as a member of Waka’ royalty, Calakmul could keep the city as a satellite. Any lasting loyalty, however, hinged on her success as queen of Waka’.

Clues found on the stelas suggest that Lady K’abel continued to outrank her spouse, even after their wedding. For example, compared to her husband’s portrait, the queen’s likeness was created using better-quality stone carved more skillfully. In addition, she faces to her right, a convention some Calakmul carvers used to identify a scene’s focus. There are also cartouches on the stela that identify the queen by her Snake Dynasty birthright, “lady snake lord,” rather than a married name, and also include the title ix kaloomte’, the female version of an honorific reserved for the most exalted rulers and dynasties. And, her stela’s inscriptions state that Lady K’abel led the ceremony at which the monument was dedicated as well as other rituals marking the end of a 20-year calendar cycle in A.D. 692. These ceremonies, which the Maya believed were necessary for the continuation of time, were generally performed only by a city’s highest-ranking leaders.

While the paired stelas, which were likely commissioned by Waka’ rulers to serve as propaganda, may not represent the day-to-day realities of Lady K’abel’s time in power, archaeological research has provided evidence that she excelled as a stranger queen who won over the residents of her new home and secured its alliance with her native Calakmul. This work includes excavations of two graves that have revealed details of Lady K’abel’s tenure. Burial 39, which was discovered in 2006 inside a pyramid in Waka’, belonged to someone of great status interred around the time Lady K’abel arrived in Waka’, probably the king who preceded her and her husband’s rule, based on the tomb’s age and burial goods. Inside the tomb, researchers found human remains laid on a stone bench accompanied by 23 painted ceramic figurines arranged as they would be during a royal resurrection ceremony. The tableau’s central character, likely the deceased king, knelt next to a spirit embodied by a deer. Other characters appeared to be performing ceremonial rites: One royal wielded a syringe for administering hallucinogens while a dwarf held a conch shell trumpet that he played to open a portal to the underworld. The scene also included a ceramic figure of a queen whose appearance and accoutrements resemble the depiction of Lady K’abel on her stela. Navarro-Farr and her colleagues believe this figurine portrays Lady K’abel as a young woman, and her inclusion in the ritual scene speaks to her importance as a leader in Waka’.

More insights into Lady K’abel’s career have come from Navarro-Farr’s 2012 excavation of Burial 61, a tomb that almost certainly held the remains of the queen herself. Anthropologists have determined that the individual buried there died during middle age or older, following a physically active life, based on markers of muscle attachments and wear and tear on the skeleton. But they have not been able to determine the individual’s sex or conduct genetic analysis because the bones are too fragile. Still, artifacts found within the tomb tie the skeleton to Lady K’abel. Archaeologists discovered a palm-size pink alabaster jar carved to depict an aged face emerging from a nautilus shell, with the glyph for “lady snake lord” etched into its side. This type of identifying inscription is highly unusual for a grave good. “It’s very rare to have that kind of smoking gun in a tomb,” says Navarro-Farr. The tomb also contained ceramic vessels from across the Maya world, indicating that Lady K’abel had been a successful diplomat. Meanwhile, her role as a sorceress was suggested by the presence of ritual items, including a pyrite mirror, a snuff jar for hallucinogens, stingray spines, and a potbellied effigy in the act of self-decapitation.

Mourners did not build a new structure to hold Lady K’abel. Instead, her tomb was dug into a long-standing monument in the heart of Waka’. “It was really an astute political decision on her part to be buried there,” says Navarro-Farr. Other royal graves, including Burial 39, which contained the figurines, were in areas that only high-status individuals could access. Lady K’abel’s tomb, in contrast, was part of a public building that could be visited by residents from all walks of life. And it seems locals did frequent the memorial to venerate the queen for generations after her death. Around and on the building, Navarro-Farr and her team discovered piled-up accumulations of human bones, utilitarian pottery, and other humble goods. They believe Waka’ residents placed household wares and their ancestors’ bones near the tomb as offerings to the deceased queen. “There’s a depth of emotion and symbolic meaning in what people appear to be leaving behind,” says Navarro-Farr. The skeletal remains, if indeed they did belong to past family members, would be among the most meaningful examples of this phenomenon. The archaeologists also identified remnants of small fires around the building, which might have been lit by residents paying tribute to Lady K’abel. For Navarro-Farr, the finds in and around the tomb reflect how Lady K’abel ruled as well as how she was remembered: as a cosmopolitan diplomat and skilled priestess who kept the city safe from Tikal. “She is probably the most important of the many Snake queens,” says Navarro-Farr.

At the same time Lady K’abel was fashioning herself into a ritual and diplomatic leader, Lady Six Sky was cultivating a very different legacy as a fierce military strategist. Although known as Lady Six Sky since scholars first began deciphering Maya glyphs in the 1960s, recent epigraphic work has translated her Maya name, Ix Wak Jalam Chan Ajaw Lem, more precisely as Lady Six Weaver Sky Lord Jewel. This moniker likely alludes to the jade part of the loom used by the moon goddess. “It’s a beautiful name, and she was a remarkable politician,” says University of Alabama archaeologist and epigrapher Alexandre Tokovinine.

Lady Six Sky’s illustrious pedigree was inscribed prominently on multiple monuments at the city of Sa’aal, today known as Naranjo, in northern Guatemala. Her father, King B’ajlaj Chan K’awiil, or Lightning Sky (reigned A.D. 648–ca. 692), was born into the royal family at Tikal, but fraternal feuds led him to establish a splinter dynasty at Dos Pilas in Guatemala. In A.D. 650, the fledgling city was attacked by the Kaanul king. Shortly after, B’ajlaj Chan K’awiil betrayed his Tikal heritage by becoming a vassal of the Kaanul.

A Dos Pilas princess, Lady Six Sky entered a diplomatic marriage with the king of Sa’aal, which was about 90 miles northeast of her homeland, nearly in the shadow of Tikal. According to four separate inscriptions found at the site, in A.D. 682 she arrived there with an entourage of supporters, and promptly led a temple ceremony to affirm her legitimacy. Five years later, she bore a son, K’ahk’ Tiliw Chan Chaak, or Smoking Squirrel, presumptive heir to the throne of Sa’aal. “She did all of those things expected of her as a royal woman,” says Ardren. “And then she just went off the rails in terms of doing whatever she wanted to do.”

A confluence of external pressures and internal drive likely fueled Lady Six Sky’s ascent. In A.D. 693, just a decade after her marriage, her five-year-old son became Sa’aal’s king, and Lady Six Sky became queen regent. Scholars have deciphered many texts written on stone monuments from Classic Maya cities, but all remain silent about her husband’s fate. Given the intercity clashes at the time, researchers suspect he may have been captured or killed by the rulers of Tikal. “Whatever happened to the husband happened very quickly,” says Tokovinine. Lady Six Sky was left with a child who was now king and with rebellious provinces that sensed vulnerability at Sa’aal, weakness in the Kaanul realm, and the growing strength of Tikal. The queen didn’t wait to defend herself and her city. She launched an offensive campaign against her known enemies as well as potential insurgents. Under her leadership, Sa’aal attacked its own provinces, destroyed and depopulated cities, and subjected captives to public humiliation and death, compelling client kingdoms to resubmit to Sa’aal and its patron, Calakmul.

One stela found in Naranjo declares that the city battled its enemies and burned five rival cities over a period of five years. Scholars debate whether these fires were metaphorical, ritual, or real acts of war, and question how much these histories, likely commissioned by Lady Six Sky, were embellished. Tokovinine has led excavations and deciphered hieroglyphic inscriptions at one of these reportedly burned cities, called Bahlam Jol by the ancient Maya and Witzna by modern archaeologists, which is located in northeast Guatemala, near the border with Belize. The team’s work seems to confirm the queen’s scorched earth assaults. Tokovinine and his colleagues uncovered charred plaster, charcoal, and ashes coating Late Classic period (ca. A.D. 600–750) stairways, benches, courtyards, and other structures across the site. They also found stelas from the time that had been toppled and smashed.

Tokovinine’s team analyzed a sediment core spanning 1,700 years taken from an adjacent lake. The core contained several thin layers of charcoal, each less than a half inch thick, suggesting periodic small-scale conflagrations. It also contained one charcoal layer measuring more than an inch thick, evidence of an enormous blaze that has been radiocarbon dated to the decade during which inscriptions record that Bahlam Jol was torched. In layers formed during the years following that fire, the sediment core shows a sharp decrease in types of clay originating from land, which are typically shed into the lake by humans living and farming nearby. It seems the forces from Sa’aal didn’t burn just the city, says Tokovinine, they also burned all the trees, gardens, and fields. “It’s not just kings fighting against kings, nobles fighting against nobles,” he says. “If a Maya king states on monuments that they burned a city, they actually burned the city.”

Following the fire, it seems that Bahlam Jol’s population dwindled and didn’t recover for at least 50 years. Tokovinine and his team did not find mutilated skeletons or any evidence that the locals were killed. Thus, he suspects that Bahlam Jol’s residents were forcibly relocated to other settlements in Sa’aal’s domain. Tokovinine believes Lady Six Sky did what she thought was necessary to maintain the status quo and that her actions were perfectly in keeping with what was typical of Maya kings at the time. Anticipating regional, and perhaps internal, challenges, she forced neighboring cities to reaffirm their allegiances to her as queen regent of Naranjo, native princess of Dos Pilas, and loyal subject of the Kaanul of Calakmul.

Lady Six Sky ensured she would be remembered. Several stelas found in Naranjo show the stranger queen with a hieroglyphic emblem of her native Dos Pilas, underscoring her superior bloodline and divine right to rule. Two of these monuments depict her as a militant ruler, standing on the naked body of a captive. According to Ardren, this aspect of the portraits mimics portrayals of kings, who were sometimes shown treading on vanquished warriors. Yet in the same portraits, Lady Six Sky wears a beaded jade skirt and other items that liken her to the moon goddess.

Although their styles differed greatly, Lady K’abel and Lady Six Sky both succeeded as stranger queens in their adopted homes. For the period during which they ruled, Calakmul seemed to wield more power than Tikal. Yet broader political events eroded the alliances the queens had worked to secure. In A.D. 695, Calakmul lost a battle to Tikal and then began to decline gradually through the eighth century A.D. as its rival’s fortunes continued to rise. Inscriptions found on stelas across the Maya world document several successful attacks by Tikal or its allies on the cities loyal to the Snake Dynasty, and during the tenth century A.D., the Kaanul’s once-great capital at Calakmul seems to have been abandoned. Though the rule of the Snake Dynasty ended, inscribed monuments and other archaeological evidence preserve the biographies of Lady K’abel and Lady Six Sky, two of the world’s most influential women during their reigns.