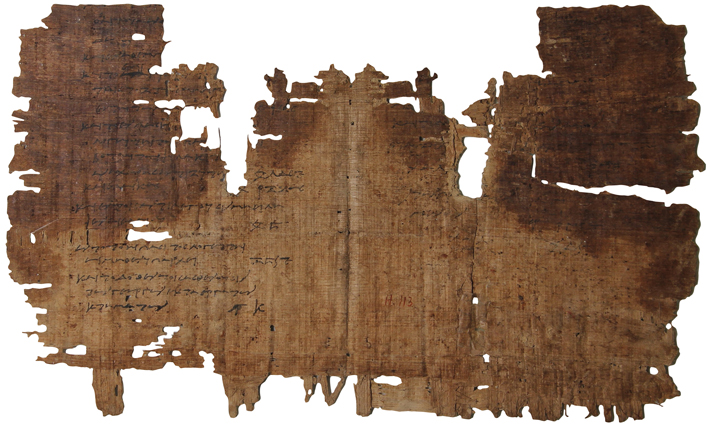

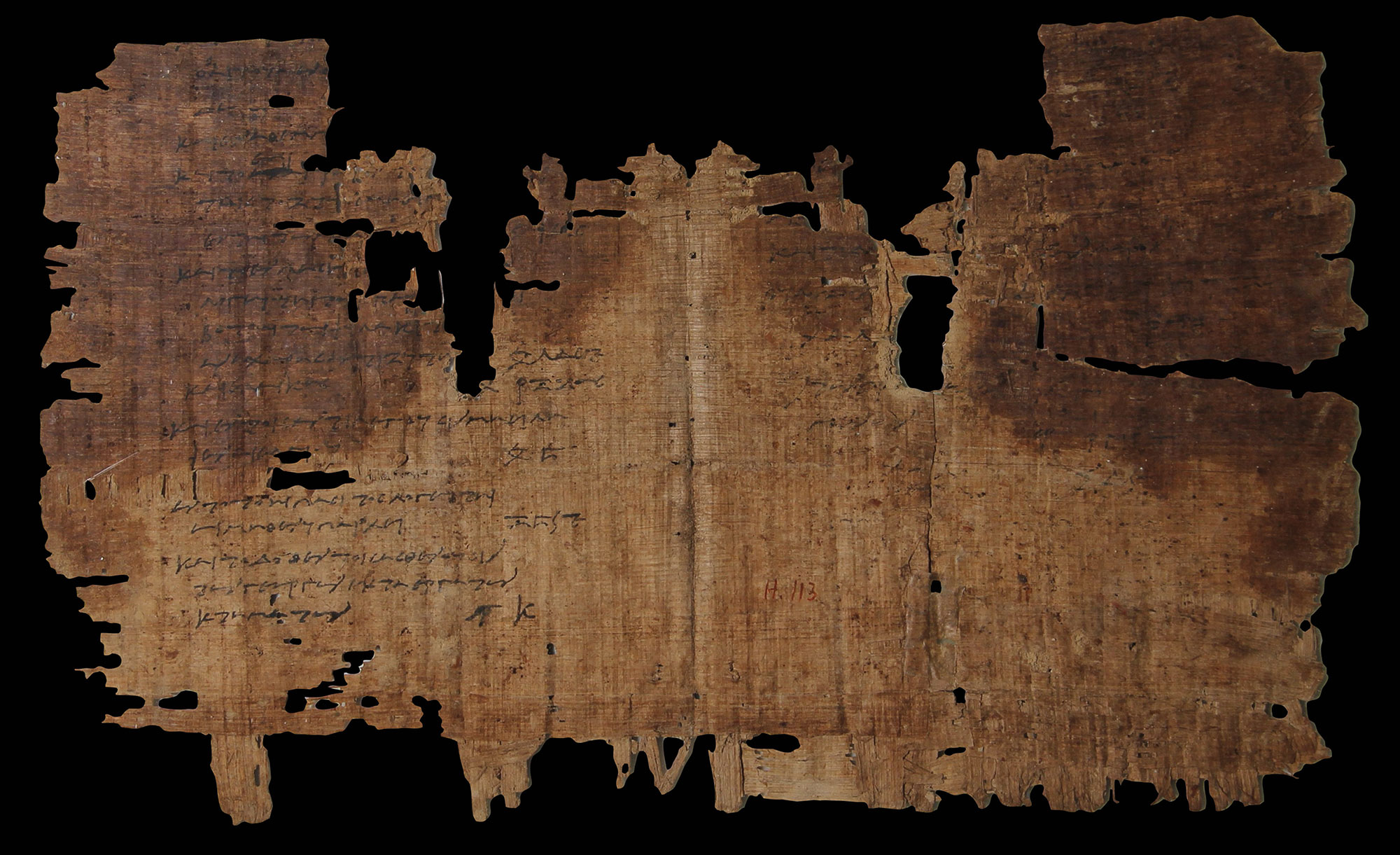

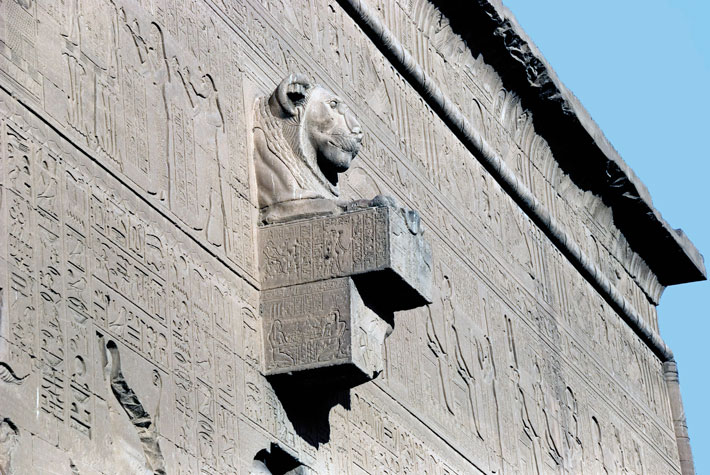

A 10-by-6-inch piece of papyrus is, researchers now believe, part of the world’s first book. And, like many of the volumes that fill offices, libraries, and homes, it has had many lives. The papyrus fragment, which was unearthed along with hundreds of other pieces of papyrus at the site of El Hibeh in 1902, began as a bound document dating to 260 B.C. that recorded taxation rates for beer and oil scrawled in Greek letters using black ink. The sheet was then removed from its binding and sent as a letter before being transformed once again when its other side was painted with images, including one depicting a son of the falcon-headed god Horus, and reused as wrapping for a mummy during the Ptolemaic period (304–30 B.C.).

Using microscopic and multispectral imaging, a team led by conservator Theresa Zammit Lupi of the University of Graz learned how the book was made. “You have a plain sheet of papyrus, folded in two, written on, and turned into a booklet,” says Zammit Lupi. “The different bifolios, or single sheets folded in the center, were attached via tackets, flexible material used to join two things together, similar to a modern ring binder.” The presence of holes for the tackets to pass through, a handful of which still have remnants of thread, and the symmetrical ink transfer across the precise fold at the center, confirmed that the bifolio had once been bound within an ancient manuscript. “An accountant must have detached the bifolio from the book, folded and sealed the letter, and then passed it on to a creditor or a debtor,” says Zammit Lupi. The discovery pushes the origins of bookbinding back by centuries. “The oldest book previously known was from the first or second century A.D., so this predates anything by up to 400 years,” Zammit Lupi says. “The book could be indicative of how transactions happened, of how people lived, wrote, and passed information to each other. Most importantly, we learned that the structure of the book, as opposed to a scroll, existed well before we thought.”