Features From the Issue

-

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2025

ARCHAEOLOGY magazine’s editors reveal the year’s most exciting finds

Courtesy of the Caracol Archaeological Project, University of Houston

Courtesy of the Caracol Archaeological Project, University of Houston -

Features

The Cost of Doing Business

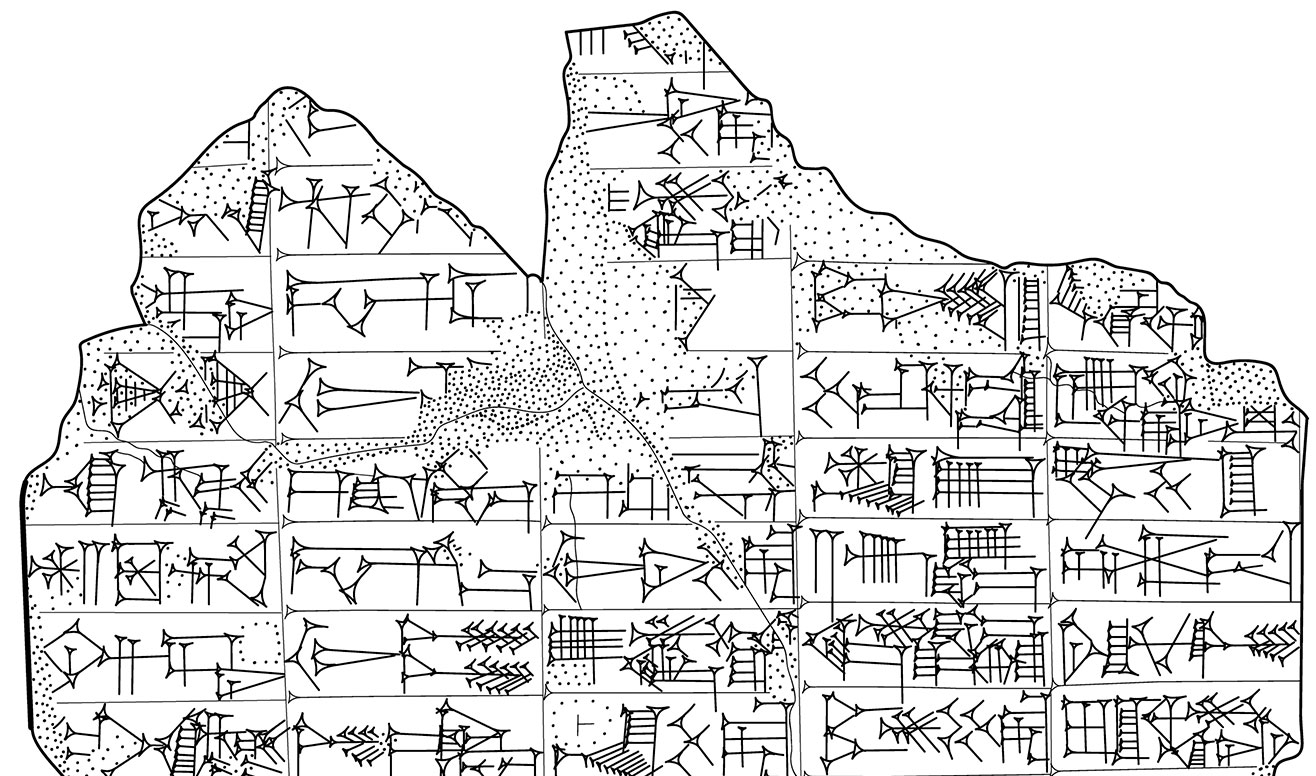

Piecing together the Roman empire’s longest known inscription—a peculiarly precise inventory of prices

Ece Savaş and Philip Stinson

Ece Savaş and Philip Stinson -

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/ Rogers Fund, 1930

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/ Rogers Fund, 1930 -

Features

Taking the Measure of Mesoamerica

Archaeologists decode the sacred mathematics embedded in an ancient city’s architecture

Courtesy Claudia I. Alvarado-León

Courtesy Claudia I. Alvarado-León -

Features

Stone Gods and Monsters

3,000 years ago, an intoxicating new religion beckoned pilgrims to temples high in the Andes

Courtesy John Rick

Courtesy John Rick

Letter from France

Letter from France

Neolithic Cultural Revolution

How farmers came together to build Europe’s most grandiose funerary monuments some 7,000 years ago

Artifact

Artifacts

Sardinian Bronze Figurines

Digs & Discoveries

-

Digs & Discoveries

The Lion of Venice Roars

AndrCGS/AdobeStock

AndrCGS/AdobeStock -

Digs & Discoveries

Purple Purchasing Power

Barry Gaulton/Ferryland Archaeology Project

Barry Gaulton/Ferryland Archaeology Project -

Digs & Discoveries

An Old Flame

Michael Shenkar & Maria Gervais

Michael Shenkar & Maria Gervais -

Digs & Discoveries

Full Nesters

LukasChrobak/AdobeStock

LukasChrobak/AdobeStock -

Digs & Discoveries

A Sicilian Gift Horse

Courtesy Davide Tanasi

Courtesy Davide Tanasi -

Digs & Discoveries

Stop, Tomb Thief!

Courtesy Michelle Langley

Courtesy Michelle Langley -

Digs & Discoveries

The Palace Times

Courtesy Nicholas Cahill

Courtesy Nicholas Cahill -

Digs & Discoveries

In Local News

Courtesy Michael Searcy

Courtesy Michael Searcy

Off the Grid

Off the Grid January/February 2026

Prophetstown, Indiana

Around the World

VIRGINIA

When English colonists founded Jamestown in 1607, they brought much-needed horses with them. According to recent examination of equid bones, they also brought donkeys, which are not mentioned in historical records. Isotope analysis indicates these animals weren’t transported from England but perhaps were picked up mid-journey in western Africa. This may explain why they aren’t listed on any ship’s manifest. The donkeys were, unfortunately, butchered by desperate colonists during the “starving time” winter of 1609–1610.

Related Content

LATVIA

Prehistoric stone tools such as blades and projectile points have long been associated solely with men. However, a survey of material from the enormous Zvejnieki necropolis determined that between 7500 and 2500 b.c., women were just as likely—or even more so—to be buried with stone tools than were men. This is forcing a reconsideration of gender stereotypes in prehistory.

Related Content

IRAQ

A surprisingly ancient monumental structure was unearthed at the site of Kani Shaie, at the base of the Zagros Mountains. The 5,000-year-old building likely served a public or religious function. Its architecture shows strong connections with Uruk, 300 miles to the south, which is often called the world’s first metropolis. The discovery indicates that Kani Shaie was not as peripheral as once thought. Instead, it was deeply entwined with the Fertile Crescent’s major social and political developments in the Early Bronze Age.

Related Content

Slideshow: A Roman Emperor’s Most Unusual Monument

The Roman Empire may have been fracturing by the end of the third century a.d., but the city of Aphrodisias, in present-day southwestern Turkey, was on the rise. The town’s sculptors were renowned across the empire, and archaeologists excavating there have found exquisite Roman statuary and architecture from before, during, and after this period, in many cases preserved in situ. Aphrodisias had shrewdly cultivated its relationship with Rome for centuries. An Aphrodisian friend of the emperor Augustus (reigned 27 b.c.–a.d. 14), who claimed lineage from Aphrodite, funded a lavish new temple in the city’s sanctuary of the goddess. Aphrodisias’ extravagant baths were dedicated to the emperor Hadrian (reigned a.d. 117–138). In a.d. 301, the emperor Diocletian (reigned a.d. 284–305) and his deputies ordered that a long, cumbersome edict—a list of maximum prices for 1,400 goods and services—be prominently displayed in cities across the empire. Local leaders in Aphrodisias could not let slide the opportunity to impress the emperor. The text, which scholars call the Edict of Maximum Prices, or the Prices Edict, was inscribed across the facade of the stateliest and most important administrative building in the city, known to archaeologists as the Civil Basilica.

Archaeologists have discovered more than 40 copies of the Prices Edict, most in fragmentary form, around the Roman world. The Aphrodisias inscription of the edict is among the most complete, but it exists in hundreds of marble pieces that fell from the Civil Basilica’s facade. In the late 1990s, archaeologists, epigraphers, and architects undertook an ambitious project to reconstruct the edict, reassembling the 250-square-foot inscription and reimagining the appearance of the collapsed building on which it was emblazoned. To read our article about Aphrodisias’ magnificence, the mystifying decree, and the massive reconstruction project, click here.

Slideshow: The Meaning in the Measurement

Established around A.D. 670 in present-day Mexico’s Morelos State, Xochicalco was among the most powerful of the city-states that rose in the wake of the fall of the city-state of Teotihuacan. Xochicalco is known for incorporating a range of cultural influences from Teotihuacan, the Maya, and peoples living in other areas of Mexico. This mélange is apparent in the city’s most important building, the ornately carved Pyramid of the Feathered Serpents, which stands on its Main Plaza. Architectural historian Geneviève Lucet of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and archaeologist Claudia I. Alvarado-León of the College of Morelos recently discovered that Xochicalco’s rich amalgam of influences may have also been embedded in its architecture. They found that the city’s designers used two distinct measurement systems. One is based on a unit known as the zapal, equaling 1.47 meters, or 4.82 feet, which was first documented at Maya sites on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The other is based on a unit known as the maitl, equaling 1.68 meters, or 5.51 feet, which is associated with sites in central Mexico such as Teotihuacan. It is, however, unclear exactly where each unit was first used. Thus, to avoid prematurely attributing specific cultural origins to the units, Lucet and Alvarado-León refer to the zapal as U7 and the maitl as U8. To read our full article on the meaning of measurement at Xochicalco, click here.