In the Greco-Roman world, racehorses were potent symbols used by both individuals and the state to express power, encourage civic pride, and celebrate special events. For the Greeks, chariot racing likely began sometime around 1500 B.C. and became a central element of their most sacred festivals. A memory of these early contests appears in Homer’s description of the funeral games honoring the fallen warrior Patroclus, during which Greek kings and heroes race once around a tree stump for the prize of a female slave. Perhaps a century after the founding of the Olympics in 776 B.C., chariot and jockeyed races were included in the games. This provided an opportunity for families to display their “hippic”—or horse—wealth as social and political capital, explains historian Donald Kyle of the University of Texas at Arlington.

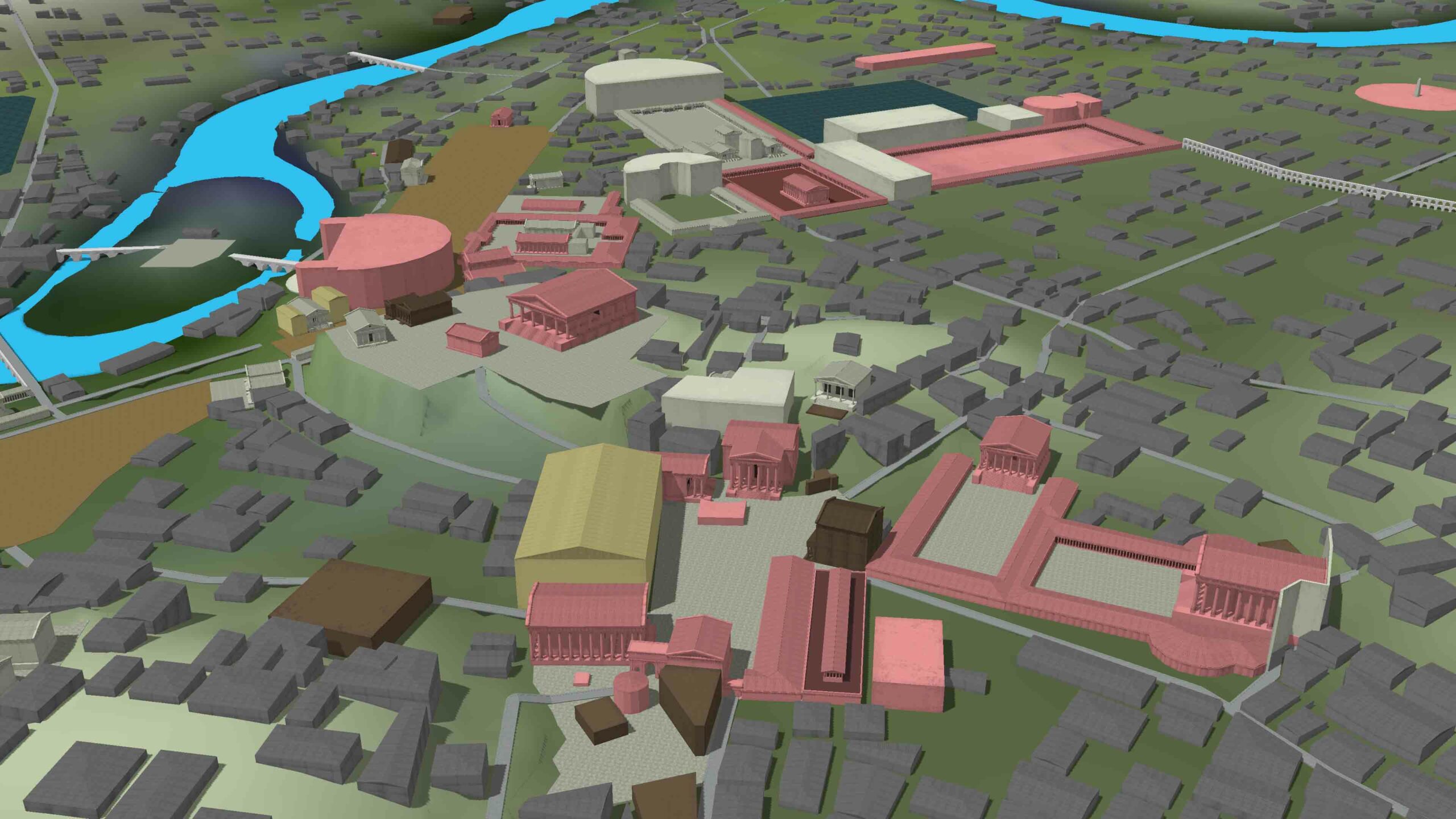

Yet for the Romans, hippic contests were just as often part of extravagant state-sponsored displays intended to entertain the masses. The historian Livy says that the first and largest Roman hippodrome, the Circus Maximus, was built by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome (r. 616–579 B.C.), in a valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills. Though originally a simple open oval space similar to a Greek hippodrome, the Romans gradually created a massive stadium-style building that, by the first century A.D., could accommodate perhaps as many as 250,000 spectators. While there were certainly other crowd-pleasing events such as gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome, “chariot racing is the earliest and longest-enduring major spectacle in Roman history,” says Kyle.