In 1498, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama created shock waves in Europe when he reached and returned from the Indian coast—and its valuable spices—by sailing all the way around Africa, a 24,000-mile journey. Da Gama found both success and hostility in the Indian Ocean, so when Portuguese king Manuel I dispatched him to the Indies again, in 1502, he went equipped with an armada of 20 ships and instructions not only to acquire spices, but also to harass and destroy the Muslim shipping industry that had monopolized the spice trade. One of these ships, Esmeralda, was captained by da Gama’s uncle, Vicente Sodré. Though the infamously brutal Sodré was directed by da Gama to patrol the Indian coast and protect Portuguese interests, he opted to sail toward the Arabian Peninsula in search of conquest and the rich plunder of Muslim ships. In 1503, Esmeralda and its crew, including Sodré, were lost in a storm off the coast of present-day Oman.

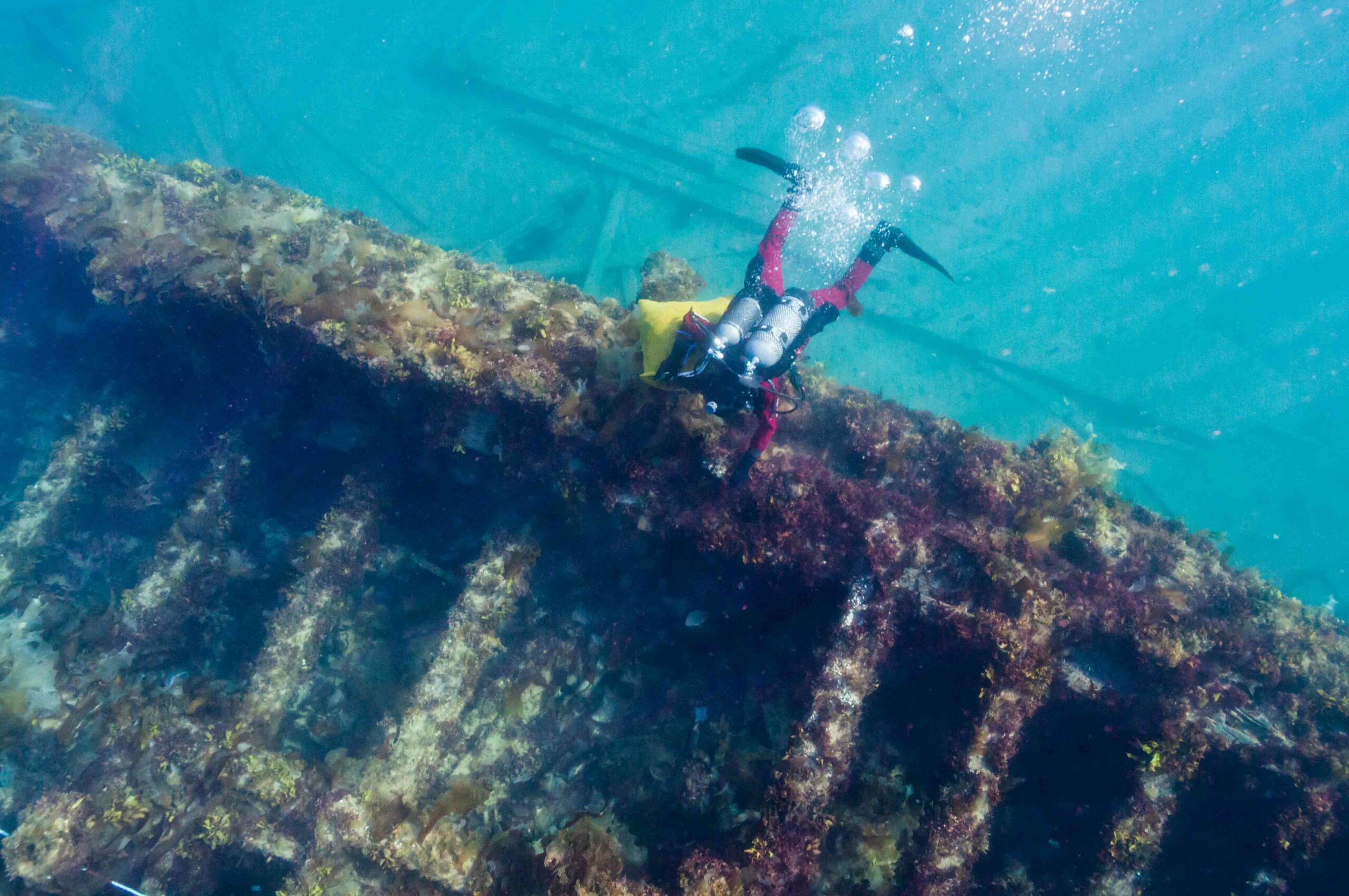

For five hundred years, Esmeralda remained a footnote to the Age of Discovery—until divers discovered its possible wreck site in 1998, on the island of Al Hallaniyah, 25 miles south of the Omani coast. Over the past three years, an archaeological project led by the Oman Ministry of Heritage and Culture and Blue Water Recoveries Ltd. has investigated the early sixteenth-century shipwreck. More than 2,800 artifacts have been recovered by archaeologists, including elements of the ship’s rigging, ceramics, coins, artillery, firearms, munitions, and trade goods. These objects are not only helping to confirm the ship’s identity, but are also providing valuable information about early Portuguese exploration. “As the earliest ‘Ship of Discovery’ ever to be found and excavated by archaeologists,” says project director David Mearns, “we knew that virtually every artifact recovered could provide new insights into how the Portuguese conducted navigation, trade, and naval warfare during this historically important period.”

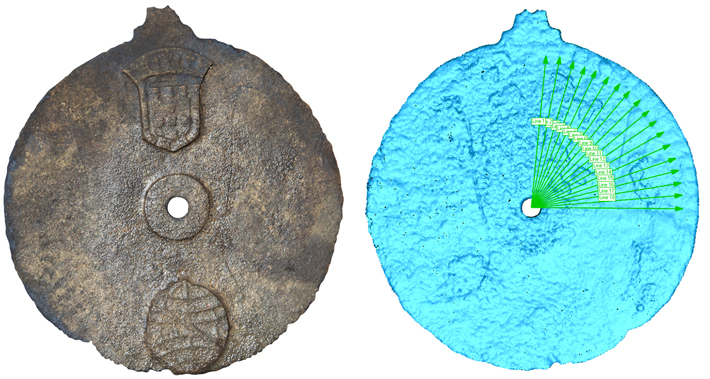

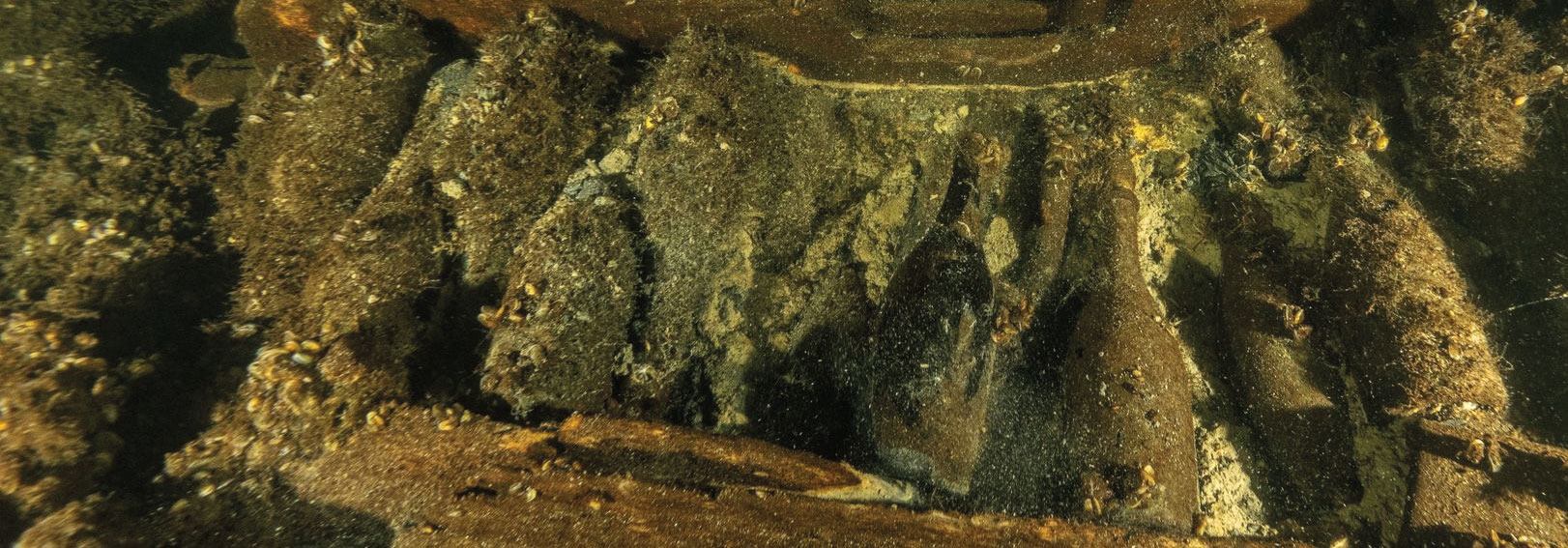

Because the ship’s cargo had remained underwater for more than five centuries, many of the artifacts were badly corroded and difficult to analyze. Researchers relied on imaging technology to gather information invisible to the naked eye or that would require destructive techniques to obtain. A CT scan of the ship’s bell allowed some of its faded lettering to be read. Thus far, the numbers 498 and the letter M have been identified, which experts believe may be part of the inscribed year 1498 and, perhaps, the name Esmeralda.

Another CT scan was performed on a clump of 24 silver coins, which had corroded into a large mass and were too brittle to be separated. The image revealed the presence of a Portuguese índio coin, one of the rarest coins in existence. The silver índio—of which there is only one other surviving example—was minted by Manuel I in 1499 after da Gama’s first return from the East, and was designed specifically for trade with India. Because it was only minted for a short time (it was replaced in 1504), this discovery has been a useful tool in helping both date and identify the shipwreck. “Even at this relatively early stage in the archaeological assessment of the wreck site,” says Mearns, “the evidence strongly indicates that the wreckage we found is from Sodré’s Esmeralda.”