Aboard the Canadian Coast Guard ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a team of marine and terrestrial archaeologists, hydrographers, the ship’s captain, and a helicopter pilot gathered to finalize the day’s plan. It was September 1, 2014, and they were in the waters of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, searching the west coast of King William Island and the eastern part of Queen Maud Gulf—some 540 square miles of sea. The team, led by Ryan Harris, a senior underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada, had been looking since 2008 for signs of perhaps the two most famous ships lost in the search for the Northwest Passage: the reinforced British bomb vessels HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, led by Sir John Franklin and missing since the late 1840s.

Scott Youngblut, a Canadian government hydrographer, was heading out from Laurier on a helicopter to a small, uninhabited island off the western edge of Nunavut’s Adelaide Peninsula to set up a GPS station that would help him chart the local waters. The area being searched is near where, in the nineteenth century, an Inuit elder had reported rummaging through an abandoned ship. Alongside Youngblut were Doug Stenton, Nunavut’s director of heritage, and Robert Park, an archaeological anthropologist from the University of Waterloo, who had come along to survey the island. Before landing, Stenton noted two promising signs: the absence of polar bears, and the presence of what appeared to be clear cultural features, including tent rings and small stone mounds indicative of supply caches. After just 20 minutes on the ground, helicopter pilot Andrew Stirling called Stenton over. Before them was a 17-inch, U-shaped iron fitting partially embedded in sand.

Stenton was intrigued by the find. It was different and more substantial than other items thought to have come from Franklin’s ships, such as nails and spikes. Those artifacts had been discovered on or around King William Island, to the northeast. Stenton picked up the 12-pound piece of iron to look for the telltale broad arrow that would identify it as property of the British Royal Navy, which had commissioned and outfitted Franklin’s expedition. “When I opened my hand I saw the number 12—and a broad arrow—stamped into the bottom,” Stenton recalls.

That evening on Laurier, Stenton, Harris, and the Parks Canada crew examined the find, as well as two wooden disks they had discovered. Because of the iron fitting’s size, they guessed it had come from Erebus or Terror, and not from one of the smaller boats Franklin’s crew is known to have used after their ships had become icebound. Harris concluded that the iron was most likely part of a boat-launching mechanism called a davit pintle, and that the disks were possibly plugs for a deck hawse, an opening through which a ship’s anchor chain passes into a storage space below the deck.

“You can imagine [as the ship was crushed by ice] the mast breaking down and the riggings and lines and sails and all kinds of things drifting ashore on ice,” says Stenton. “The find just suggested there was a very good possibility that there was a wreck in the area.”

The search to determine the fate of Franklin’s 1845 expedition began almost immediately after the realization that the ships were lost. Since then, explorers have turned up bodies, bones, weapons, tools, a sunken rescue ship, and even a handwritten note with precise coordinates of where the quest veered so horribly off course. But the shipwrecks themselves remained elusive, lost amid a constellation of archipelagos and the whims of sea ice. After nearly 170 years, Canadian archaeologists were finally on the cusp of a breakthrough in one of the great maritime mysteries. The potential find carried the weight of decades of anticipation and even modern geopolitical ramifications, as the nations that surround the now increasingly ice-free Arctic jockey for access to the natural resources that are thought to lie beneath it.

Sir John Franklin and his crew aboard Erebus and Terror—134 men in all—set sail from England on May 19, 1845. Their mission was to find the long-sought Northwest Passage through the treacherous Arctic seas that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Franklin was at the helm of Erebus, while his second-in-command, Francis Rawdon Crozier, captained Terror. By late July, the ships (now carrying 129, after five men fell ill and were sent back) were in Lancaster Sound, the eastern entrance to the Arctic Ocean. They left word with the captain of a passing whaling vessel that the mission was going according to plan, and then set off into the unknown.

Back in Britain, alarm only arose after the expedition’s three-year mark came and went with no word from Franklin. Their disappearance into the void sparked a string of ambitious but unsuccessful rescue efforts funded first by the British Admiralty, and then privately by the explorer’s wife, Lady Franklin. In 1850 alone, 10 separate expeditions were launched, including one helmed by Robert McClure, who took an easterly route into the Arctic through the Bering Strait. McClure ended up losing his ship, HMS Investigator (“Saga of the Northwest Passage,” March/April 2012), but he and most of his crew were rescued, and he managed a feat for which he was celebrated upon his return: His men were the first to traverse the Northwest Passage (by sea and sled).

McClure encountered no evidence of Franklin, but another 1850 expedition found, on Beechey Island, mummified remains identified by crude wooden markers as William Braine and John Hartnell, who served on Erebus, and John Torrington, who was part of Terror’s crew. The most troubling realization about the fate of the expedition came in 1859, when a search party led by Royal Navy explorer Francis Leopold McClintock discovered a stone cairn at Victory Point on King William Island. Inside was a handwritten note dated May 28, 1847, reporting that all was well with the Franklin expedition despite a winter stuck in the ice. But an update written around the margins of the paper detailed how desperation had taken hold less than a year later. Dated April 25, 1848, the update stated that Franklin had died just days after the first note was left, and that the decision had been made to abandon the ships. What remained of the crew—105 men—headed on foot in the direction of “Back’s Fish River,” which would have led them south.

More evidence of the survivors was eventually uncovered, much of it grisly. Later expeditions found buried or mutilated human remains—some alone, some in groups of several dozen. It is not known if starving crew members resorted to cannibalism, or whether the condition of the remains was caused by wild animals. Other traces included iron nails, metal cutlery, tools, knives, and wood fragments that the crew carried with them on their doomed march. But just as important, or more, are the oral histories and eyewitness accounts, collected by later search parties, of the Inuit, who traveled seasonally through the area for centuries.

The most detailed of these accounts—and the most useful for the eventual identification of remains from the wrecks—were recorded by U.S. Army Lieutenant Frederick Shwatka and Charles Francis Hall, another American Arctic explorer. In 1861, Hall credited Inuit accounts for his discovery of “relics” from Martin Frobisher’s 1578 Arctic expedition. He hoped for a similar breakthrough in the Franklin search. “I am convinced that were I on King William’s Land and Boothia (Peninsula), and could I live there two years, I could gather fact[s] relative to Sir John Franklin’s expeditions...from the Innuits that would astonish the civilized world,” he wrote in his diary.

Hall found neither records nor survivors from the Franklin expedition, but he did meet an Inuit elder he identified as “In-nook-poo-zhee-jook,” someone he called “a walking history of the fate of Sir John Franklin’s expedition.” The man lived in a hut that was “full of articles from the ships,” and he presented Hall with a large silver spoon believed to have belonged to Franklin. He also drew for Hall a detailed map based on his recollection of what he and others had spotted. The first point he marked was an area just off the Adelaide Peninsula.

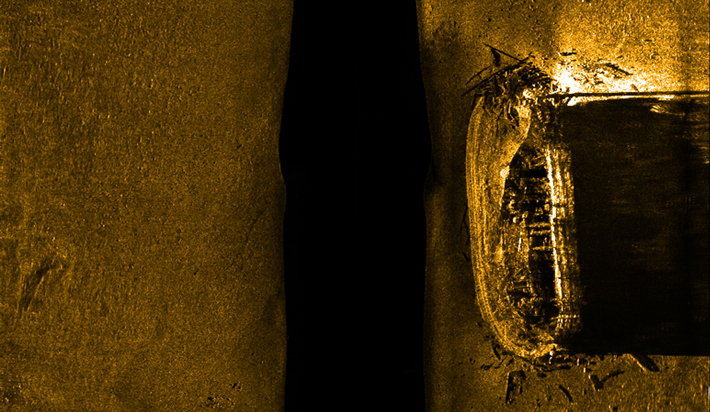

The day after the island survey, Harris, his Parks Canada colleague Jonathan Moore, and two technicians launched their underwater sonar equipment in the shallow waters off the island. As the technicians wrangled the sonar, Harris emerged on deck from the cabin below just in time to witness the emergence of a golden mass on the sonar screen. “That’s it!” Harris cried out in jubilation.

“I remember sitting in Captain Bill Noon’s quarters on Laurier when Ryan and the others told us about the discovery,” recalls Stenton. “There was this momentary pause and I thought, ‘Oh, what have we done here? We found it and now what?’ It just sort of hits you like a ton of bricks.”

For all the money and energy spent—and lives lost—looking for the ships and survivors, what may be most noteworthy is that the ship was found in almost exactly the same area indicated by the Inuit elder in 1869. The spot, in the area of Wilmot and Crampton Bay, northeast of O’Reilly Island, is more than 60 miles south of the ship’s last documented location. The discovery, which would make international news in the coming days, was particularly important for the Inuit who have stood sentinel over the Arctic for generations. “It validates their version of events,” says Harris.

The next step for Harris and Moore was to determine which ship they had found. They ran a remotely operated camera around the wreck to film and measure the vessel. The mission came to an abrupt halt as they were secretly flown back to Ottawa to join the Canadian government in announcing the discovery to the world. It was a find important to both Canadian pride and the nation’s sovereign claim to portions of the Arctic and the mineral, oil, and gas reserves below. The announcement was made by no less than Canada’s then–Prime Minister, Stephen Harper.

It would take several weeks of poring over images taken from a 3-D topographic scanner for Harris to determine the precise dimensions of the ship. He knew that one of the ships was three feet longer and two feet wider than the other. From those dimensions, and the locations of the ship’s foremast, mainmast, and hatches, the team concluded that they had found the larger of the two ships, the one captained by Franklin himself—Erebus.

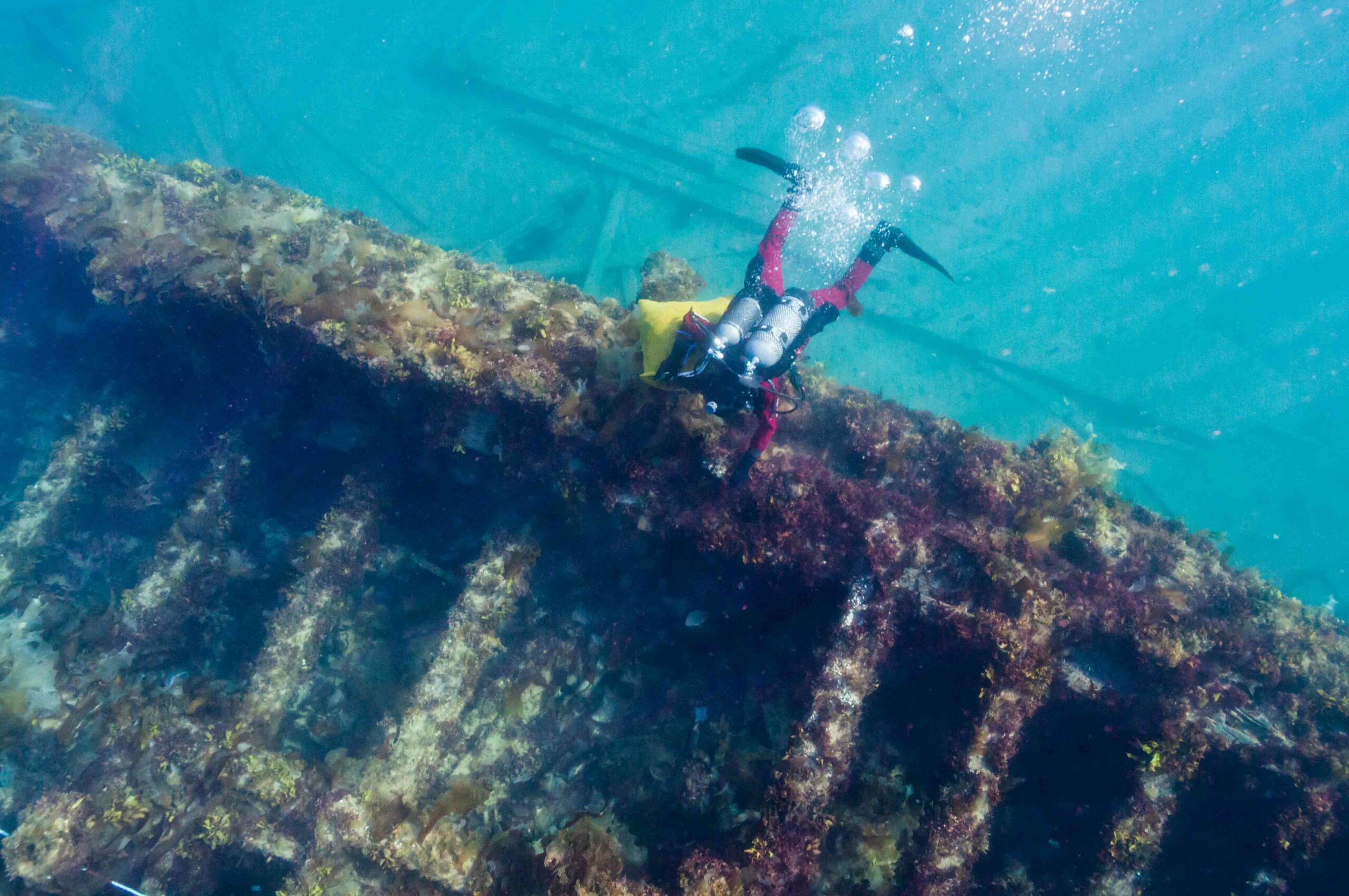

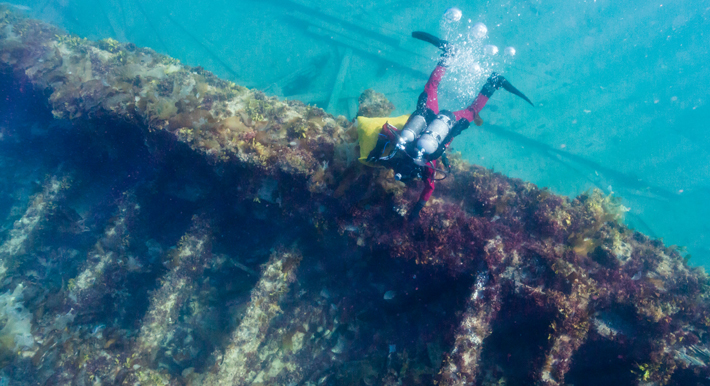

Harris and Moore had to wait through the announcement, a day of rest, and a major storm—a reminder of the dangerous power of the Arctic—before they could don dry suits and investigate their prize, which sits upright in just 30 feet of water. “The visibility was so bad [because of the storm] that we couldn’t see the wreck when we got to the bottom,” Moore says.

Their dive plan was simple and methodical: survey the wreck, document its condition, determine the most easily accessible artifacts, and search for anything that could establish the ship’s identity beyond doubt. On their first dive, Harris recalls, he could make out scattered timber as he approached the wreck from the stern. Out of the glowing murk, “a monolithic wreck” came into focus. Harris and Moore checked the perimeter of the ship and then swam to the upper deck, moving from stern to bow in parallel, shining their lights on artifacts and hailing one another to peek through holes where the ship’s hull had opened.

“By dumb luck, I happened to be on the starboard side and Ryan was on the port side,” Moore says, which put him in position to find the key artifact of their search. Moore approached a green metal mass with the clear outline of a bell, cast with the Royal Navy broad arrow and the year “1845.” “It’s quite extraordinary that the date and the broad arrow were almost upright like a book, facing me, ready to read,” he says. “I’ll never forget that.” Few items hold as much symbolic value for Harris as that first find, which was retrieved on the last day of the 2014 dive and is now undergoing preservation treatments at a Parks Canada laboratory in Ottawa. “The bell is the ‘soul’ of the ship,” Harris says. It would have been used to mark the passing hours of the doomed mission, a symbol of civility and order in the face of desperation and death. “As the [Franklin] mission unraveled, at what point did even the progress of time lose significance?” Harris adds.

Subsequent dives have yielded 55 artifacts—for the most part easily accessible items sitting on the upper deck and strewn about the seafloor. Among them are one of the ship’s three cannons—a “brass six-pounder,” with three cannonballs inside—part of the ship’s wheel, a sword hilt made of wood and brass with an attached piece of fabric that could indicate whether it belonged to an officer of the Royal Navy or Royal Marines, a leather shoe or boot, and a wooden table leg that resembles one in an illustration of Franklin’s cabin on Erebus published in a London newspaper in 1845. “We’re sort of scratching the surface of a very long archaeological process,” Harris says. Daunting years of work lie ahead.

In the fall 2015 expedition, divers started cutting away kelp and other marine life to better assess Erebus’ condition. They set out reference markers to accurately record distances and locations on the wreck, and are making plans for an intensive search inside the ship. Later in 2016, Harris hopes to explore the officers’ cabins just behind the main mast, which are accessible because scouring ice floes have crushed the main beams of the upper deck. “We’re able to look in at a number of these spaces and identify both the places where certain officers would have slept and their belongings,” he says. “If you’ve got hats or woolen jackets, there is the prospect of there still being hair attached somewhere, [discoverable] if you look carefully with a microscope. We can potentially sample that and determine who was there.” Hall’s account of Inuit testimony also mentions that the Inuit at some point observed a dead man on board with “very long” teeth, and a large, heavy body that took five people to lift. The remains may still be there.

Structural reinforcement may be required to search other areas inside the ship, such as the crew’s mess area and Franklin’s quarters, both of which have been badly impacted by ice. Videos taken by the divers highlight other potential areas of interest on Erebus’ lower deck, such as the ship surgeon’s sick bay and a seamen’s chest, used to store belongings. According to Harris, “We are most interested in artifacts that will help reconstruct not just what happened but what life was like.”

As overwhelming as the Erebus project may seem, it remains only half the story of the Franklin expedition. Terror is still missing. The working theory is still that Terror—like Erebus—was carried southward in the drifting ice from the point where it was deserted, off the northwestern coast of King William Island. The discovery of Erebus, and the proof of the accuracy of the Inuit accounts, has forced Moore back into the library for the original nineteenth-century accounts of rescue missions and Inuit testimony, which may contain new leads and clues to help target multibeam sonar searches.

“What we’ve been doing and will be doing some more is looking at that Inuit testimony through a lens of discovery,” Moore says. “It’s absolutely fascinating going through every nuance, every sentence, every word recorded...and making sure that we understand and know what the Inuit observed.” Stenton also has adapted his search for terrestrial sites related to the survivors, including the wealth of untapped archaeological prospects that still exist on King William Island, where the crews set ashore for their doomed trip south. His team recently completed facial reconstructions from the remains of two crew members. Another project in the works is analyzing DNA from the remains to identify individual crew members and attempt to determine who died where.

Such is the public fascination with missing ships that Stenton has already caught himself apologizing to some Franklin enthusiasts who are mourning the loss of the mystery, and are wary of what the finds mean for the future of one of the world’s least touched and most unforgiving environments. Already the once-impenetrable Northwest Passage is host to numerous luxury cruise ships, and the territory of Nunavut is keenly aware of further tourist interest, especially in sites related to the Franklin expedition. “Those are very big issues that need to be approached cautiously,” Stenton says.

“Some people have said to me that they hoped the wrecks were never found,” he says, adding, “I try to ease the pain a little bit by telling them that we haven’t found Terror yet, so it’s not a total disappointment.”

Slideshow: Remains of an Arctic Shipwreck

In 1845, Sir John Franklin led a doomed two-ship expedition to navigate the long-sought Northwest Passage through the treacherous seas that connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. For the last 170 years, dozens of expeditions have fruitlessly searched for HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—until 2014, when archaeologists from Parks Canada finally discovered the wreck of Erebus, near where Inuit accounts from the late 19th century reported a vessel trapped in ice.