Around 8,000 years ago, in the woodlands of what is now the eastern United States, hunter-gatherers began to make stone objects with holes drilled in them that have no parallel in any other prehistoric society. Today, archaeologists call these highly polished and sometimes elaborate objects “bannerstones.” The name was coined by early twentieth-century scholars who thought they must have been mounted on shafts and used as emblems or ceremonial weapons. But just why they were made only during the so-called Archaic period, which ended around 3,000 years ago, has been debated by archaeologists for more than a hundred years.

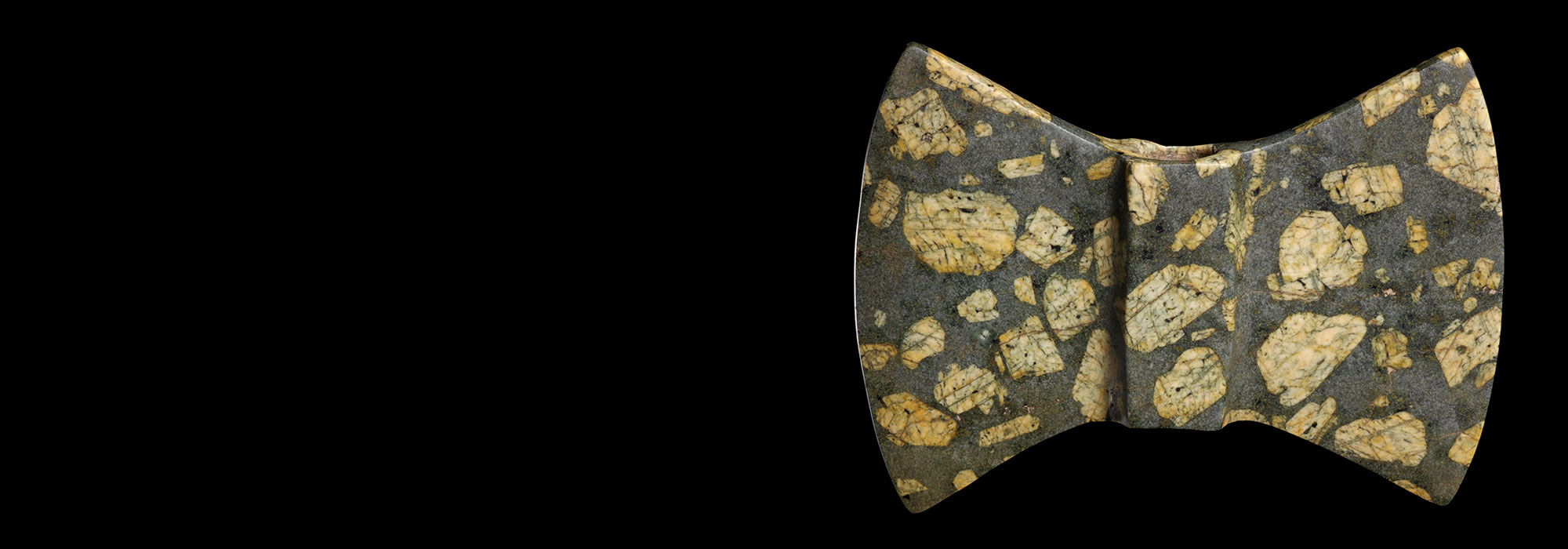

Some have taken the position that they were not strictly ceremonial and were used as weights that imparted force and accuracy to spear-throwers, or atlatls. They were made from a wide variety of stone materials and in different sizes and shapes, though many take a “butterfly” form, so they may not all have been used for the same purposes. “Archaeologists are mystified by bannerstones,” says University of Florida archaeologist Kenneth Sassaman, who has studied the artifacts in detail. “We can’t know for sure what Archaic people were doing with them.”

The latest scholar attracted to the mystery of bannerstones is Fashion Institute of Technology art historian Anna Blume, who is making an intensive study of these artifacts in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. She has spent countless hours studying the objects. “Bannerstones get noisier and noisier the more time I spend with them,” says Blume. “These extraordinary Native American works from deep time still have a lot to tell us.” Her project is one of several that are providing a new vantage point from which to observe these intriguing objects, which Blume calls “still lifes in stone.”

In the 1930s, University of Kentucky physicist-turned-archaeologist William Webb began excavating graves left by a culture known as the Shell Mound Archaic in Kentucky’s Green River Valley. Helped by a team of Works Progress Administration laborers, Webb unearthed a number of the drilled stones, which were by then already known as bannerstones. Because he found them lying between hooks and handles made of antler, he assumed they had once been connected to a wooden atlatl that had since disintegrated.

Atlatls are essentially throwing sticks with a handle on one end and a hook on the other that can hold a spear. By drawing the spear-thrower back and then hurling it forward, a hunter can use the atlatl as a lever to launch a spear, sending it farther and with more power than if launched only by hand. Webb assumed the bannerstones were meant to somehow increase the efficiency of such spear-throwers. Perhaps inspired by his background in physics, Webb made a long study of atlatl mechanics and determined that bannerstones were used as weights that added velocity and power to the spears hurled from the atlatl. Since Webb published his ideas in 1957, at least two generations of archaeologists have tried to replicate his results. Despite the fact that they are often still referred to as atlatl weights, scholars have largely been unable to show that bannerstones improve atlatl efficiency. “Like a lot of my colleagues, I experimented early on with atlatls and bannerstones,” says Alan Harn, curator emeritus at Dickson Mounds State Park in Illinois. “I must have cast hundreds of spears trying to understand them, but I never got a bannerstone to add thrust and power. They slowed me down.” Eventually, Harn gave up.

In 1983, longtime avocational archaeologist and replicator of ancient technology Larry Kinsella won the Atlatl World Open Grand Championship in Wyoming using an atlatl without a bannerstone. The next year he returned and used an atlatl fitted with a bannerstone that he had made himself. To his dismay, the bannerstone helped with neither distance nor accuracy, and Kinsella’s performance fell well below that of the previous year. He lost his title as world champion. “That’s when I decided to really understand bannerstones,” says Kinsella. “I knew that they were gorgeous and aesthetically pleasing and probably had some ceremonial role, but I figured they must have originally had some utility too—just not as atlatl weights.” He experimented with replicating different kinds of atlatls and pecked, scraped, and perforated dozens of pieces of sandstone, limestone, quartz, and other rocks to create a variety of bannerstones. After thousands of atlatl trials with and without bannerstones, he realized that his performance at the world championship was not a fluke. Bannerstones did nothing to improve the efficiency of a spear-thrower.

While observing the behavior of white-tailed deer as he picked mushrooms in the woods near his Illinois home, Kinsella had an epiphany. After the end of the last Ice Age, he knew, white-tailed deer would have been the main prey of hunters in the eastern woodlands of North America. Stalking these animals in deciduous forests with an atlatl presents a challenge. Because of the dense forest cover a hunter must get close to prey but not startle it—any movement or sound will scare a deer away. Ambush from a tree is not feasible with an atlatl, so the hunter must be on the ground and have enough clearance to draw back the spear-thrower. A deer will often spot a hunter positioned in ambush and stare at them for two or three minutes, during which time the hunter must remain still. “A hunter had to be prepared to outwait a deer with an atlatl at full draw, ready to launch,” says Kinsella. “And they had to be prepared to wait several minutes before hurling the spear.” But Kinsella notes that in those minutes, fatigue can set in, enough to make throwing a spear accurately very difficult. Through experimentation, he found that bannerstones acted as counterbalances, lengthening the time he could remain motionless holding an atlatl in launch position before his muscles began to tire.

To test the hypothesis, anthropologist Herman Pontzer, now of Hunter College, hooked Kinsella up to an electromyography machine, which measures electrical waves produced by muscle activity. He then had Kinsella hold an atlatl in prelaunch position for two minutes with and without a bannerstone, then repeated the same trial several days later. Pontzer found that Kinsella experienced much less muscle strain when holding an atlatl with a bannerstone attached. “That showed that bannerstones do give a hunter a mechanical advantage, just not the one Webb thought,” says Kinsella. Harn, for one, has greeted Kinsella’s work enthusiastically. “It’s great to have someone like Larry spend so much time on this and figure out the nuts and bolts,” says Harn. “He showed us what we were missing. When I heard his idea that they were counterbalances, I thought, ‘It all clicks. That’s what the Archaic people were using them for.’”

Sassaman agrees that bannerstones likely began as a mundane tool to aid hunting. He says examples of crude versions of the stones found in domestic trash show they probably didn’t always occupy a ceremonial role in Archaic life. But over the millennia, as bannerstone forms evolved, he thinks it is clear they also played a nonutilitarian role in society. Sassaman has studied nearly 150 bannerstones excavated by early twentieth-century archaeologists in the Savannah River Valley of Georgia and South Carolina. He says that changes in their morphology can help us reconstruct the history of Archaic cultural change. The earliest bannerstones were made by the Shell Mound Archaic people around 6000 B.C. By around 3800 B.C., people in the Savannah River Valley had begun to fashion them. These early bannerstones were tubular, and many were very refined. “These finely finished ones are found exclusively in graves during this period,” says Sassaman. Some were found in burials of women and children, perhaps suggesting they had already attained a meaning outside the context of hunting. “Maybe they were needed for passage to the other world,” says Sassaman. Then, around 3200 B.C., a more diverse group of bannerstones began being made, and were even exported to northeast Florida, which had no suitable sources of stone. At this point, Archaic people seem to have stopped including bannerstones in graves.

Around 2700 B.C., people in the Savannah River Valley began to make bannerstones in oversized elaborate shapes that archaeologists call “hypertrophic.” Sassaman thinks the impulse to create these dramatic objects may have been linked to changes in the ways different groups interacted with each other. “This is the most fascinating phase,” says Sassaman. “Some of these bannerstones are monsters, as much as half a foot in diameter. There’s no way a hunter needs to be carrying around a stone that big.” He notes that these bannerstones are also not found in graves, but clustered in mounds that were sites of social gatherings. Interestingly, while these bannerstones are more elaborate, they are also less varied in form. Sassaman says a similar thing happens at the same time among Archaic people living around the Great Lakes and on the Atlantic coast from what is now Virginia to Massachusetts. All these regions lie on the outskirts of the area occupied by the Shell Mound Archaic culture, where the tradition of making bannerstones was the strongest, but which is not known to have produced the hypertrophic versions. “I think these exaggerated forms have to do with intercultural relations,” says Sassaman. “Here you have people outside the Shell Mound borders, and by making these hypertrophic forms these people are yelling loudly, ‘This is who I am!’” Bannerstones then could have become emblems of ethnic identity, made by people acutely aware of the other groups that lived in the eastern woodlands. “We often think of Archaic people exclusively in terms of how they related to their environment, but they had to interact with other ethnic groups too,” says Sassaman, “and bannerstones were probably part of that.”

At the American Museum of Natural History, Blume has combed through a collection of some 500 bannerstones that were collected a hundred years ago or more and have since gone unstudied. Of those, she’s selected 61 for further analysis. Blume has spent months photographing them from multiple angles and taking a series of measurements. She plans to make all her data and images accessible online to scholars and the public in the near future. Blume, who also studies the ancient Maya, says that many bannerstones, especially the hypertrophic examples, are so distinct and beautiful that in any other context scholars would assume they were prestige objects, made for the rich and powerful. But Archaic societies were egalitarian. “They had no social or class distinctions,” says Blume. Though bannerstones may have played a larger ceremonial role within Archaic groups, she believes the bannerstones themselves would have had special meaning to the people who fashioned them. “These pieces are highly individualized,” says Blume. “They record an intimate sensibility, and a personal touch is obvious in each one.”

Blume points out that even today, modern flintknappers like Kinsella take great pride in their abilities and the stone artifacts they produce. Making an elaborate bannerstone would have presented a different challenge than making spear points or axes and might have been a particular source of satisfaction for prehistoric flintknappers. “With points you are limited to stone that is flakeable and will make a good point,” says Blume. “But bannerstones are pecked and ground, so they could be made from a wider range of materials.” Granite, limestone, and quartz are all unsuitable for spear points, but each would have had its own aesthetic appeal. Some bannerstones were clearly made with the specific geology of such stones in mind, preserving fossils or colorful banding. “They offered a bigger lithic palette to knappers,” says Blume, “and that was important because you might make hundreds of points in a lifetime, but you would make only a few bannerstones.”

Blume believes Kinsella has shown that bannerstones were once used as atlatl counterbalances during hunting and also agrees with Sassaman that the hypertrophic forms played some kind of ceremonial role in Archaic societies. She also adds a third category—miniatures. Long suspected to be modern fakes, miniature forms of bannerstones are often just two inches across, and Blume is convinced they were also made by Archaic people. “These are representations of bannerstones, rather than bannerstones themselves,” says Blume. “Perhaps they had a ceremonial role, or perhaps they were meant simply to be enjoyed aesthetically.” Blume has also selected a number of preforms, or unfinished bannerstones, to study. “When is an object considered finished? That is always a fascinating question,” says Blume. “It’s important for us to consider these preforms, which we know were sometimes being exported or traded by the people who made them.”

Blume is also fascinated by bannerstones that were broken and then reused. Broken bannerstones often have a second perforation, which could have been used to thread rope through. Perhaps these were worn as necklaces or were suspended from staffs during ceremonies. Some also seem to have been intentionally broken in an act archaeologists call ritual “killing,” a term Blume doesn’t feel is quite right. “I think of them as ritually broken rather than killed,” says Blume. “‘Broken’ is an interesting word. You break bread with someone, for instance, and it has positive metamorphic possibilities.” Blume thinks that by intentionally breaking a bannerstone, an Archaic person wasn’t necessarily bringing it to the end of its useful life, but perhaps aiding its transition to another form.

After around 1500 B.C., bannerstones seem to disappear from the archaeological record, even though atlatls continue to be used for at least another two millennia. Blume notes that it is possible that people began using nets to kill deer, and bannerstones lost both their utilitarian and metaphoric roles. “For whatever reason, they became obsolete,” she says, “and something else took their place in these peoples’ conceptual toolbox.” Blume points out that complex stone pipes appear around this time, and that finely made, drilled stone figures depicting birds may have been mounted on atlatls, perhaps occupying the cultural niche once filled by bannerstones. The skills and aesthetic appreciation Archaic people once lavished on these unique objects changed focus, and the bannerstone tradition vanished.