Westminster Abbey is one of the most famous buildings in Christendom. It has stood witness to signal events, serving as the site of English coronations for almost one thousand years, hosting dozens of royal weddings and funerals, and containing the tombs of monarchs, poets, scientists, and countless other notable Britons. Recently, it was the site of an unusual archaeological dig. The excavations did not take place outside on the Abbey’s grounds, as might be expected, but instead in the triforium—an arcaded gallery some 70 feet above the nave, or central aisle.

The 20th-century poet John Betjeman described the triforium as offering the “best view” in Europe. Today, many people have, without realizing it, experienced that vantage point on television. The cameras that broadcast important Abbey ceremonies are often stationed in the triforium to provide a bird’s-eye view of the events. The gallery itself has not been open to the public since it was built in the thirteenth century, but that is set to change. Abbey authorities have decided to transform it into a museum space, soon to be known as the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries. Since the triforium is currently only accessible via a narrow wooden spiral staircase, a new tower, which will provide visitors with direct access to the triforium from outside, is being constructed. This is the first major architectural addition to the Abbey in 350 years.

In the lead-up to these changes, church officials have faced the daunting task of both renovating the space and removing material that had collected there for 700 years. “The triforium gallery has never had a meaningful use and it served as an attic,” says archaeologist and Westminster Abbey consultant Warwick Rodwell. But what an attic it is! Over the centuries, it has gradually become filled with broken, precious objets d’art, architectural adornments, and even long-forgotten and displaced stone monuments. “It was the place where you stored all the things you didn’t know what to do with, including old furniture, books and papers, unwanted stained glass windows, and all sorts of odds and ends,” he says.

According to Rodwell, the triforium was not always intended to be used for storage. When it was first designed and built in the 1250s under King Henry III, it was likely conceived as an area that would contain upper-floor chapels and other usable spaces. But, because of changing fashions, that plan never came to fruition. “Chapels [above the ground level] were popular in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but their popularity waned in the mid-thirteenth,” Rodwell says. “They probably intended to lay a floor of glazed and patterned tiles, but that did not happen either.”

Because no flooring was installed for a few centuries, the tops of the protruding stone vaults from the story below remained exposed, and the crowns and recesses created an undulating, uneven surface in the triforium. “The ups and downs of the vaults would have looked like lunar craters,” Rodwell remarks. In some places, these pocketed recesses are as much as five feet deep, and for centuries they made perfect receptacles for trash and other debris left behind by the triforium’s occasional visitors.

During the eighteenth century, the famous architect Christopher Wren finally installed a wooden floor, which inadvertently served to seal in and preserve the material that had already collected in the triforium’s nooks and crannies. The floor also failed to prevent new material from accumulating. Small objects often fell through the floorboards and added to the hidden artifact assemblage below.

During the current campaign of renovations, when the floorboards were lifted, Rodwell encountered centuries-old historical debris. Since then, he has overseen the archaeological excavation of the triforium. “When I first crawled around the vaults, under the timber floors, I realized that there was considerable archaeological potential in the ‘rubbish.’” he says. “Consequently, I planned the operation of cleaning out the vault pockets in an orderly archaeological fashion. This is the first time a professional archaeological investigation of the contents of vault pockets has been carried out in the UK.” Overall, more than 4,000 trash bags containing material spanning seven centuries were filled, removed, and their contents sorted.

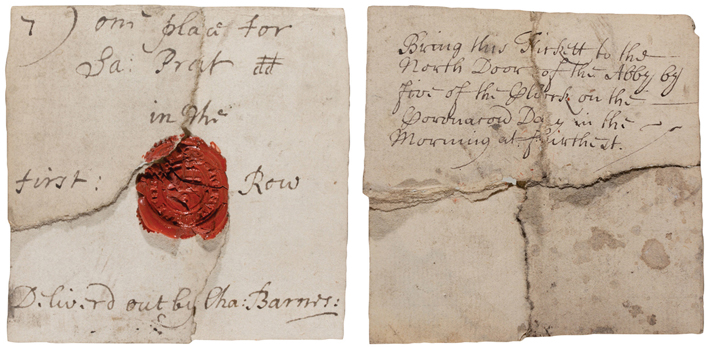

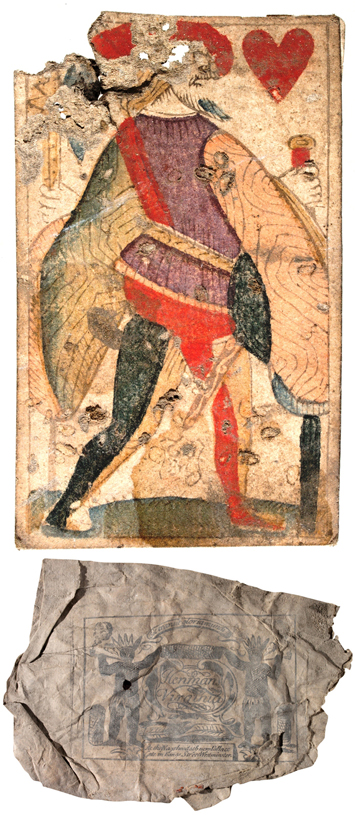

A brand-new perspective on the use of the triforium over time, and of the people who occasionally visited this difficult-to-access level, is now the result. Among the objects discovered are animal bones—leftover from meals—sherds of pottery, fragments of glass vessels, tobacco wrappers, newspapers, pages from books, a leather knife scabbard, and even shoes. A rare seventeenth-century playing card and four handwritten invitations to the coronation of Queen Anne, likely left behind by spectators who witnessed the 1702 ceremony, were also salvaged.

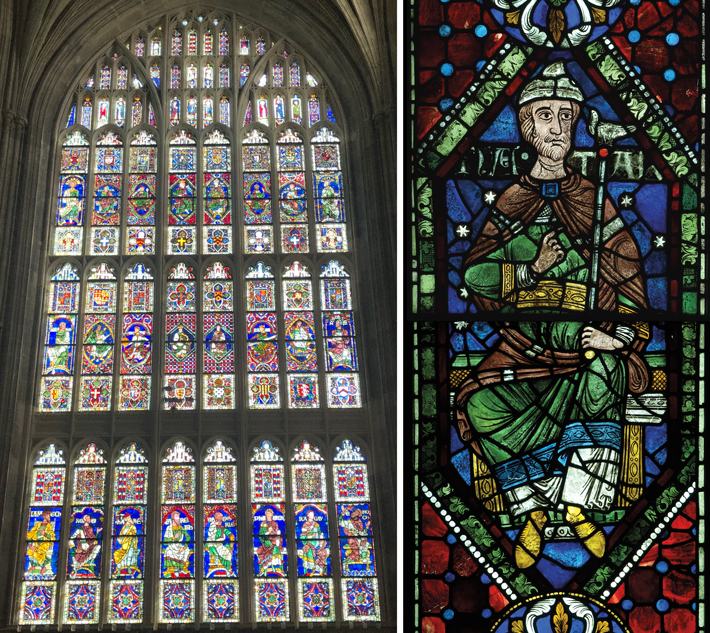

More than 30,000 fragments of stained glass, probably swept aside after windows were broken or blown out periodically during the centuries, were recovered. Some pieces have been identified as belonging to the original windows installed in the thirteenth century. They feature various designs, geometrical shapes, medieval faces, and mythological creatures. The Abbey’s glass collection has been brought to the stained glass studio at Canterbury Cathedral where experts are working to reassemble the overwhelming glass puzzle and are even creating new windows from what has been found. “In all, it is a remarkable haul of material,” Rodwell says, “with much still to be studied.

Many of England’s great churches underwent restoration campaigns during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when spaces similar to Westminster’s triforium were emptied. Unfortunately, records were not kept and valuable information was likely tossed away as trash and forever lost. “This material is not just rubbish, but a time slice through more than 700 years of the Abbey’s history,” Rodwell says. As many people can attest, the looming obligation to clean a cluttered attic is usually met with dread, but Westminster Abbey’s triforium renovation has proved both exciting and rewarding, truly lending credence to the old adage “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”