Hundreds of ancient obelisks and stelas are strewn across fields on the outskirts of Aksum, a city in the highlands of northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region. The largest of these monuments, which lies toppled and broken into sections, was carved with doors and windows to mimic a 13-story building, and once stood around 100 feet high. Weighing more than 570 tons, the Great Stela, as it is known, was hewn from a single block of granite-like rock cut from a quarry two and half miles away. At more than three times the height of the biggest of Easter Island’s moai statues and nearly 20 times heavier than the mightiest of Stonehenge’s sarsens, it is among the largest monolithic sculptures ever created and transported.

These monuments, which date to the third and fourth century A.D., once marked the tombs of kings and high-ranking officials. The names of those who erected them, and the individuals buried beneath, have been lost or forgotten over the centuries. They were the rulers of the Kingdom of Aksum, which dominated the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea region for most of the first millennium A.D. Much like the Romans, their contemporaries and occasional allies, Aksum grew from a single city into an expansive empire whose kings controlled a territory comprising parts of modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan, and the southern Arabian Peninsula. The Aksumites’ transcontinental trade routes stretched from Iberia to India, and perhaps even as far as China. They were a highly literate society, fierce warriors, and accomplished engineers and artists, and they issued their own gold coinage. The third-century A.D. Persian prophet Mani referred to Aksum as one of the world’s four great empires, along with the Romans, Persians, and Chinese. “At that time, Aksum is mentioned as one of the most powerful civilizations in the world, although people in the modern era may not know that or think of them in that way,” says Johns Hopkins University archaeologist Michael Harrower. “There has not been much archaeological attention given to Africa outside of Egypt.”

The stelas, obelisks, tombs, and ruins of major buildings, including administrative complexes and palaces, provide evidence of ancient Aksum’s thriving capital city during its heyday. Much of the modern town is built atop the ancient settlement, which has made investigation of its early history difficult. Over the past two decades, however, Harrower and other archaeologists have searched outside Aksum proper, working in both Ethiopia and Eritrea, to garner a greater understanding of the Aksumite civilization. Two recent projects, at the sites of Beta Samati in Ethiopia and the ancient port of Adulis in Eritrea, have revealed what life was like in the empire more than 1,700 years ago. These excavations have highlighted the Aksumites’ sophisticated building techniques, drawn attention to the important role that Christianity played in their culture, and, above all, underscored the existence of the trade networks that were the kingdom’s lifeblood and key to its rarely paralleled success.

The origins of the Kingdom of Aksum are difficult to pinpoint and much debated. Although its most prosperous period fell between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D., what became the Aksumite civilization can be traced back to the Horn of Africa centuries earlier, to what archaeologists call the pre-Aksumite and proto-Aksumite periods. “Archaeology indicates that the Aksumite state emerged out of the proto-Aksumite D’mt Kingdom, which flourished in the mid-first millennium B.C.,” says Washington University in St. Louis archaeologist Helina Woldekiros. During this period, people living in the Ethiopian highlands traded with Egypt and Nubia. These pre-Aksumites also shared close cultural links with the Sabaeans of the southern Arabian Peninsula. Archaeologists excavating around Aksum have shown that, in the mid-first millennium B.C., a burgeoning community inhabited the hilltop site of Bieta Giyorgis, just northwest of Aksum.

The cultural hub of the Ethiopian highlands in the first millennium B.C., however, seems to have been about 30 miles northeast of Aksum, at Yeha, a site that contains some of the oldest and largest standing architecture in sub-Saharan Africa. The most prominent of these buildings is the Great Temple, which was dedicated to the Sabaean moon god, Almaqah, and was constructed around 700 B.C. Built of finely dressed rectangular blocks, some of which are 10 feet wide, it still stands more than 45 feet high. Although archaeologists have studied the temple for more than a century, very little work has been carried out in the countryside. Given the site’s impressive architecture and its likely role as a ceremonial gathering place for local communities, it was puzzling to Harrower that no trace of any large residential settlement had ever been identified. “There’s been a lot of research on Yeha, and on the temple itself, but not really in the surrounding area,” he says. “I was struck that there was an amazing temple there but no big urban site as you might expect.”

In 2009, Harrower and members of the Southern Red Sea Archaeological Histories (SRSAH) project began surveying the rugged terrain north of Yeha on foot. They started by interviewing the local people, especially farmers, who had intimate knowledge of the landscape, about whether they knew the whereabouts of any ancient sites. One place consistently came up in their conversations—Beta Samati. “After the third or fourth person mentioned it, I thought we should go there,” Harrower says.

The archaeologists were told that Beta Samati was located near the modern village of Edaga Tabu, around an hour and a half walk from Yeha. Even before the team reached the site, it quickly became apparent that they were heading in the right direction. While they were still 20 minutes away, they began noticing pieces of pottery on the surface and abundant stone remnants of ancient structures. “We thought, ‘When we actually get to the place, it is going to be really important,’” says Harrower. And when they finally arrived, it proved to be one of the most momentous Aksumite sites ever discovered.

The ancient town of Beta Samati sits atop a hill that rises 80 feet above the surrounding valley. Its ruins, which are preserved to a depth of 10 feet in places, encompass an area of 50 acres, or the equivalent of around 40 football fields. The town was inhabited for more than 1,300 years, from the eighth century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. Spanning the pre-Aksumite and the Aksumite periods, Beta Samati thrived at the apogee of Aksum’s power, when it was an important production, trade, religious, and administrative center serving the capital city. During four excavation seasons between 2011 and 2016, a collaborative project of SRSAH and Aksum University, along with the Tigrai Culture and Tourism Bureau and Ethiopia’s Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage, explored its ruins. The team began their investigation at the hill’s highest point, as they assumed that was where the ancient town’s most significant buildings were likely to have been located. They found a network of stone walls and adjoining rooms that provided evidence of both residential and commercial activities. It appeared that the complex had not been built piecemeal, one property at a time, but in a deliberate way. “The walls were interesting because they were constructed simultaneously in a single effort,” says Harrower. “That tells us that there was some kind of communal effort and a plan.” Archaeologists found dishes, bowls, storage vessels, and grinding stones, as well as animal and plant remains, showing that some properties were used to produce, store, and consume food. They also unearthed evidence of metal and glass manufacturing, which was particularly noteworthy since it was previously thought that all glass found at Aksumite sites was imported from the Roman world.

As plentiful as the archaeological remains were atop the hill, farmers who had long cultivated the area suggested that the team turn to another location, closer to the hill’s base. “They said, ‘You should come dig at this other spot,’ because they had plowed up these huge stones that they used to build their own houses in the village,” says Harrower. The locals were correct. Archaeologists soon began to uncover the footprint of a large structure, measuring 60 feet long by 40 feet wide. “We knew it was some kind of monumental building,” Harrower says, “but we didn’t know what it was.”

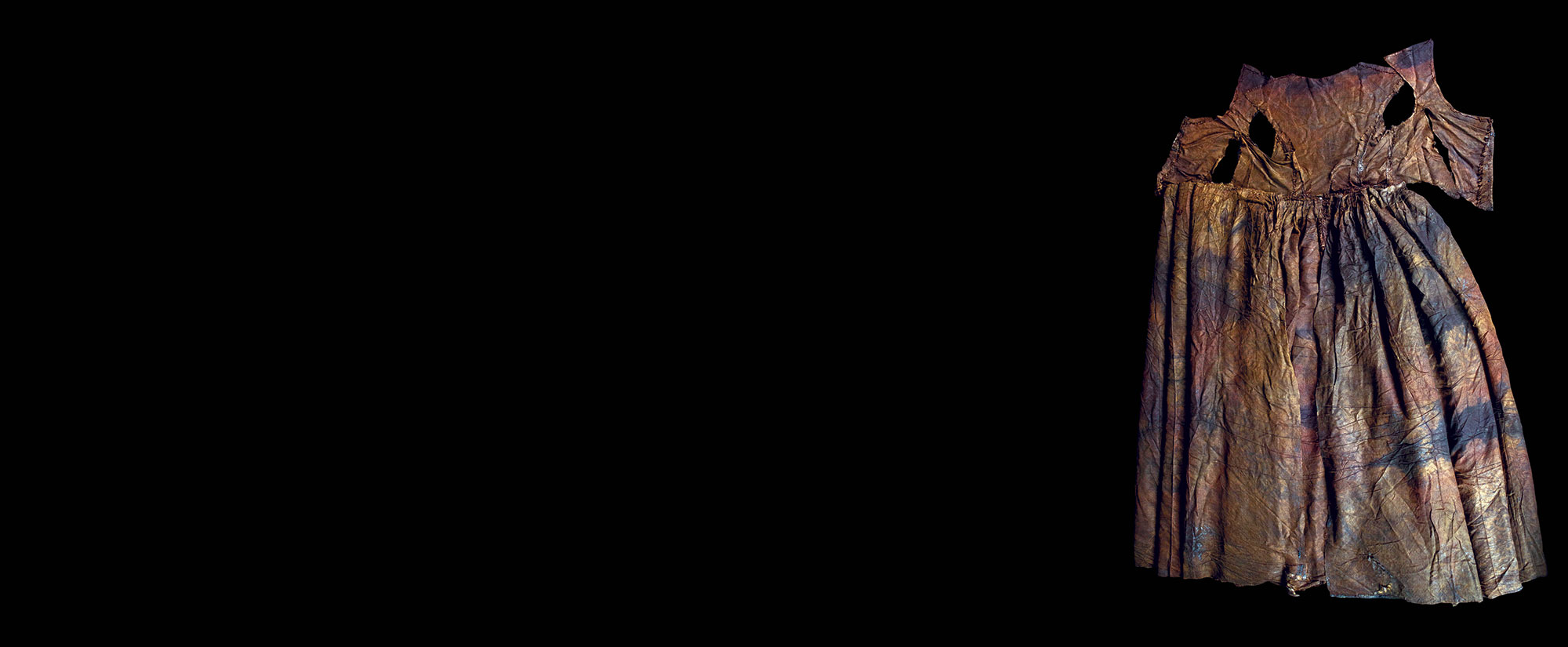

Small clues began to point to the building’s function, especially the discovery of a stone block and small stone pendant, both of which contained inscriptions in Ge‘ez, an ancient Ethiopian language. The writing on the pendant seemed to read “venerable” alongside what appeared to be an image of a cross. The stone block’s incomplete inscription was roughly translated as, “To this entrance, Christ be favorable to us.” This left little doubt that the team had uncovered an early Christian basilica.

Radiocarbon dating of wheat and barley seeds from the site indicated that the basilica was likely built in the fourth century A.D., making it one of the oldest—if not the oldest—known churches in sub-Saharan Africa. Its antiquity was not entirely unexpected, as Ethiopian tradition holds that the Aksumites were among the first in the world to adopt Christianity. According to legend, the Aksumite king Ezana (reigned ca. A.D. 325–360) was converted to Christianity by his childhood tutor, Saint Frumentius, a Christian born in Lebanon who became the head of the Ethiopian church and its first bishop. Coins issued by Ezana during his lifetime seem to support this claim. Early in the king’s reign, his coins often included, alongside his effigy, a small crescent and a disk, symbols associated with pagan southern Arabian gods. Later in his life, though, the king replaced that iconography with a single cross. “Aksum converted to Christianity in the fourth century, really much earlier than almost any other major kingdom,” Harrower says.

One of the primary reasons Christianity arrived in Aksum at such an early date is the regular contact the empire had with other civilizations through global trade networks. Not only did the empire’s location allow it access to Africa’s interior, but its position along the Red Sea fostered relationships with people and cultures in the Arabian Peninsula and beyond. “The Aksumite state’s extensive long-distance trade routes traversed the vast expanse from Nubia, located in present-day northern Sudan, to the Gulf of Aden in the Red Sea,” says Woldekiros. “These trade routes served as conduits for the transportation of commodities from Egypt, Rome, the Byzantine Empire, India, south Arabia, and Nubia.” Harrower’s team has uncovered evidence of imported goods throughout Beta Samati, including amphoras from Jordan that likely once contained oil or wine, glass beads from the eastern Mediterranean, and Roman pottery produced in North Africa.

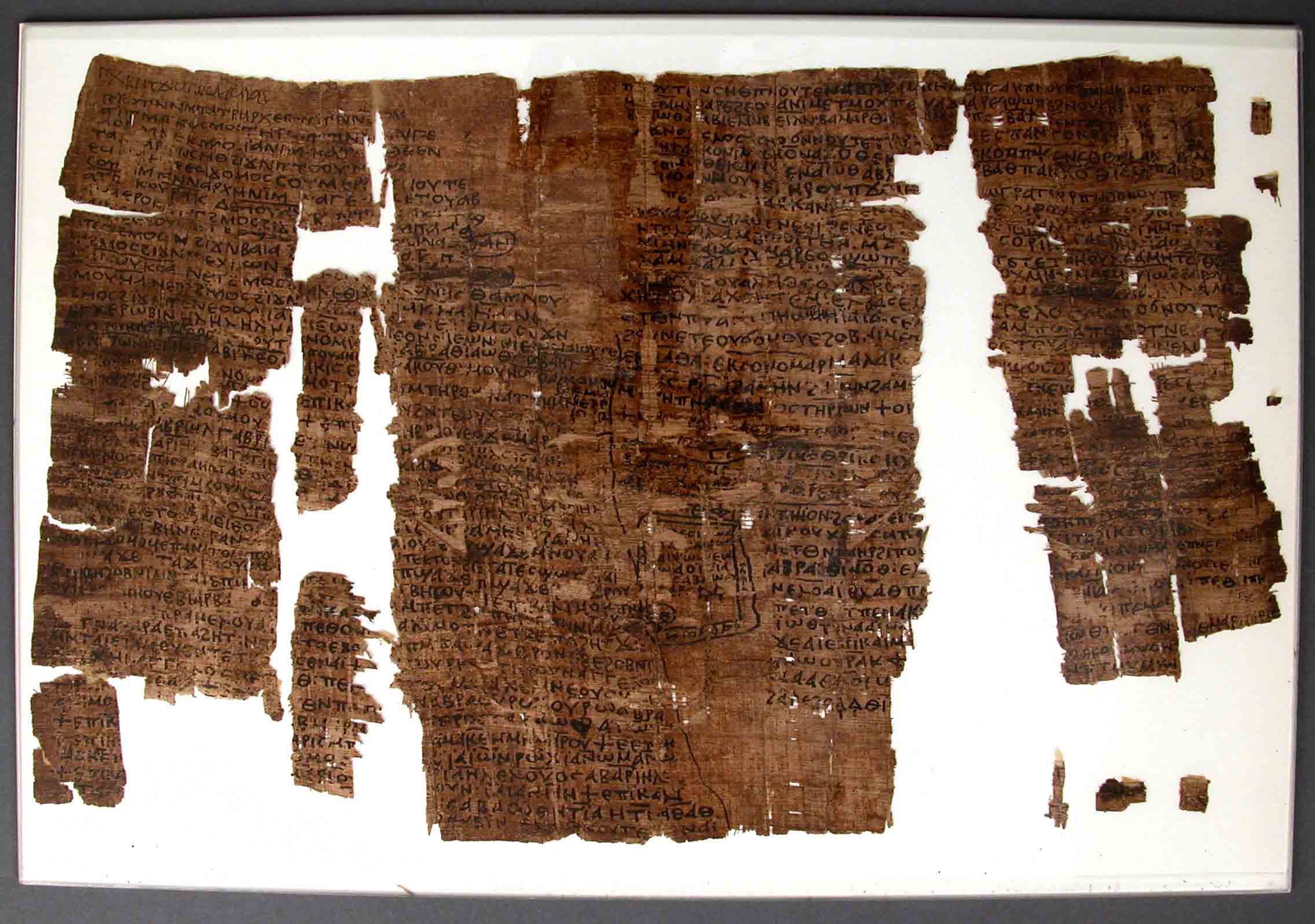

This level of cultural exchange created a diverse, multilingual society. Much like Egypt’s Rosetta Stone, the fourth-century A.D. Ezana Stone records the king’s accomplishments in three languages—in this case, Greek, Ge‘ez, and Sabaean. With the influx of foreign languages and objects came new ideas and ideologies, including Christianity. “At that time, religion was spread through commercial trade routes,” says Gabriele Castiglia, an archaeologist with the Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology. There was only one city through which everything that entered Aksum passed—Adulis. The port was the linchpin of this vital trade network. “The significance of the renowned international trading port of Adulis as the second most important city of the Aksumite civilization cannot be overstated,” Woldekiros says. It is also a site on which archaeologists have recently focused their attention.

As far back as 2500 B.C., Egyptian pharaohs launched trade expeditions to lands along the Red Sea, where they acquired exotic goods such as elephant ivory, leopard skins, and frankincense. They were among the first outsiders to pull their ships into foreign Red Sea harbors. At least as early as the first century A.D., the port that received most, if not all, Red Sea maritime traffic was Adulis. The city is mentioned as an important trade center in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century A.D. travel guide to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, as well as in the Roman author Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, which was written around the same time. Adulis continued to grow, and at the height of Aksumite power, was a vibrant settlement and the node through which wealth was funneled into the empire. “We have clear evidence that Aksum could not have achieved its great power over the southern Red Sea area without the city and the port of Adulis,” says Woldekiros.

Adulis covered around 100 acres on the Gulf of Zula, yet only around 5 percent of it has been explored by archaeologists. Over the past six years, a joint project between Eritrean authorities and Italian institutions has revealed the city’s opulence, how Christianity proliferated there, and how broad Aksumite trade networks were.

Although King Ezana and the royal court adopted Christianity in the fourth century A.D., it took time to spread from the capital to other towns and cities. By the sixth century A.D., the faith was deeply ingrained in places such as Adulis. “Adulis was founded as an emporium—a type of ancient trading post—but later became a great city, in my opinion thanks to the spread of Christianity,” says Castiglia, who is director of the Italian excavations there. “It was full of churches, bishops, and monks.” Although two smaller churches had previously been uncovered in Adulis, Castiglia’s team was on a mission to find the city’s ancient cathedral. “We know from the written sources that there was a bishop, so there must have been a cathedral,” he says. “It couldn’t be either of those two churches, because they are too small.”

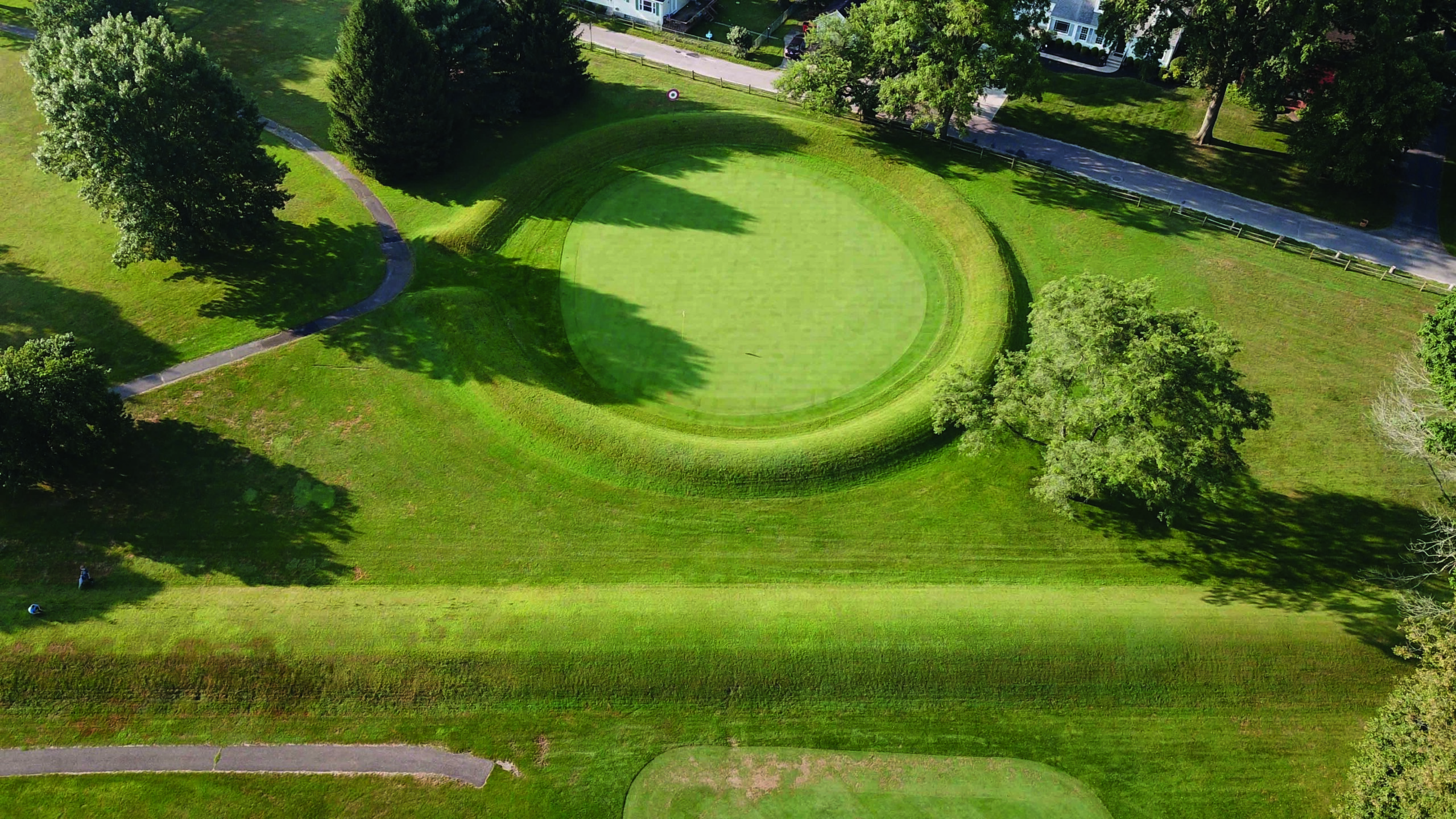

To begin their search, the team planned to revisit a site that was first uncovered by a British Museum expedition in 1868, which recorded finding an “early Byzantine church.” Detailed information about these excavations was lacking, though. Even the church’s location was uncertain since the British team had completely reburied it. As at Beta Samati, local villagers guided archaeologists where to look. Following their lead, the team uncovered sections of the building that had been excavated a century and a half earlier and carried out their own in-depth investigation that revealed the structure’s full extent. They found the ruins of a huge complex, measuring 100 feet long by 65 feet wide, that had been built upon a 10-foot-high podium. It contained a large central hall divided into three naves with a semicircular apse at one end. This plan is consistent with the typical design of early Christian basilicas.

Dating to the sixth century A.D., around two centuries after the church in Beta Samati, the grand Adulis complex is evidence of how much the influence of Christianity had grown, of the influx of wealth into the empire, and of the increased sophistication of Aksumite construction methods. Archaeological work has shown that the structure’s interior was once filled with an array of pillars and columns, ornately sculpted stone window slabs and chancel screens, and painted plaster walls. “It has better building techniques and an impressive amount of alabaster and marble,” Castiglia says. “We believe it’s the cathedral, which is why we went there—we were lucky.”

Upon examining remnants of the building more closely, archaeologists learned that much of its decoration, especially the marble, had been imported from around the Mediterranean and even from as far as the Pyrenees Mountains, 3,000 miles away. Excavations nearby have uncovered amphoras from Syria, a statuette from India, and even Chinese ceramics. “This gives you an idea about the network of contacts this area had with the rest of the world,” Castiglia says. Goods from around the globe could be found in Adulis’ shops, foreign languages could be heard on its streets, and people of different cultures mixed along its shorefront. “Archaeologists tend to see the ancient world as Mediterranean-centered because of the Roman Empire, but it was not at all,” says Castiglia. “We can easily say that back then, the world was already globalized, and the Aksumite Empire was really the key area that connected the East and the West, the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. And Adulis was the key site because it was the only harbor the empire had on the Red Sea.”

Several factors contributed to the decline of the Kingdom of Aksum, including changing climatic conditions. The coastline of Adulis gradually receded away from the city, farther and farther into the Red Sea, greatly diminishing the city’s ability to serve as an international port. The ancient site now sits more than three and half miles from the coast. Another factor may have been the rise of Islam. In the seventh century A.D., the new religion began emerging from the Arabian Peninsula. Historians believe that by the eighth century A.D., Muslim settlers had taken control of the Dahlak Archipelago, a strategic group of islands just off the coast of Adulis. It’s possible that with this powerful new neighbor the Aksumites eventually lost control of the Red Sea trade networks that had fueled their wealth and expansion.

Although the ancient civilizations of the Horn of Africa have remained on the periphery of research compared to other contemporaneous powers, the region teems with archaeological sites. In recent years, though, archaeology in the region has been halted as violent civil conflict ravages Ethiopia, and Tigray in particular. Further investigation of the monuments, temples, and cities of the region’s once-glorious civilizations has been paused and new sites await identification once work resumes. “Occasionally, people publish articles about the end of archaeological discovery, that we have found everything, and there aren’t going to be any more great discoveries,” says Harrower. “But this really isn’t the case in places like Africa. You can drive down the highway in Ethiopia and see major ancient towns and villages— they have just never been studied.”