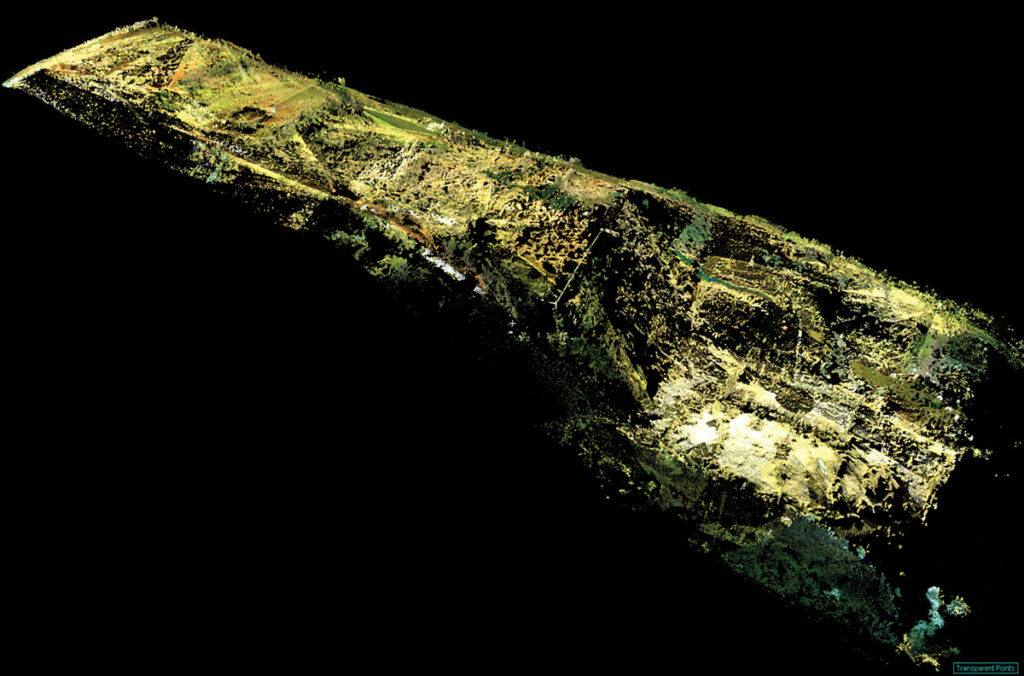

On an extinct volcano in western Java, five artificial terraces are cut into a promontory known as Gunung Padang. The terraces are buttressed with stone retaining walls and can be reached from the valley below via a staircase made up of 370 stone steps. Each terrace is covered with rectangular megalithic structures composed of hundreds of prismatic andesite blocks that geologists call columnar joints. These are igneous stones that owe their shape to repeated heating and cooling when the volcano was active millions of years in the past. Scholars believe that, centuries ago, the ancestors of today’s local Sundanese people conducted sacred rituals on these terraces. The lowest and largest terrace, Terrace 1, features a five-foot-long andesite block that makes a loud, deep sound when struck. The Sundanese call it a batu kecapi, or “stone lute.” From Terrace 5, the highest and smallest of the terraces, one can take in a spectacular vista that includes two nearby volcanic mountains. Gunung Padang draws local Muslims who read the Koran aloud amid the stones and Hindus from the island of Bali who climb the mountain’s steps to conduct rituals related to the rising of the full moon. Followers of the Indonesian martial art pencak silat practice their discipline high on the mountain.

The question of who built the megalithic structures of Gunung Padang and when has been the subject of much debate since they were recorded in 1914 by Dutch archaeologist N.J. Krom. Local stories link the site with medieval Hindu figures such as the semi-mythical King Siliwangi. The king is believed to have been inspired by Sri Baduga Maharaja, a historical figure who ruled one of the last Hindu kingdoms in western Java from about 1482 to 1521. According to one legend, King Siliwangi built Gunung Padang in a single night. Less fanciful accounts ascribe the megaliths’ construction to prehistoric people. Some researchers in the twentieth century suggested the site could have been built as early as 2500 B.C. More recently, a team of geologists who investigated Gunung Padang using remote sensing concluded that the mountain conceals much older structures. They believe these structures could have been built as early as the Paleolithic era, more than 20,000 years ago. Most Indonesian archaeologists are highly skeptical of this claim, since there is considerable evidence that the people who lived on the Indonesian archipelago at that time were hunter-gatherers who did not build significant stone structures. A paper published in Archaeological Prospection in 2023 by the geologists was recently retracted by the journal’s editors. A review of the geologists’ data showed that radiocarbon dates from soil cores used to support their interpretation were taken from samples of natural soil, not from layers with evidence of a human presence.

Archaeologist Lutfi Yondri of the University of Padjadjaran, who has dug at Gunung Padang over the course of three decades, believes its earliest megalithic structures were built some 2,000 years ago. This would make it one of the oldest stepped temples in Indonesia, which are known as punden berundak. Gunung Padang is the largest and best known of these stepped temples, but similar monuments were constructed by people who practiced traditional animist religions across Java over the course of the first millennium and early second millennium A.D. During this period, these people were in contact with Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms that flourished on the coasts of Java, Sumatra, and other major Indonesian islands.

It is possible to reconstruct, at least in part, the motivations and beliefs of those who built the earliest punden berundak because similar megalithic traditions endure throughout the Indonesian archipelago to this day. According to archaeologist Harry Truman Simanjuntak of the Center for Prehistory and Austronesian Studies, people erected megalithic structures to commemorate and appease ancestral spirits. “This practice is based on the belief that the spirits of the ancestors have the power to give blessings of prosperity, fertility, and good luck,” he says. “They could also mete out disasters to the surrounding community.” Any clan that could muster and command the labor to build and maintain a punden berundak the size of Gunung Padang must have had powerful motivations to stay in the ancestors’ good graces.

After Gunung Padang was recorded in the early twentieth century, the site was ignored by archaeologists for more than 50 years. Then, in 1979, three farmers from the nearby village of Karyamukti rediscovered the site and brought it to the attention of local authorities. Excavations carried out by the National Archaeology Research Institute in the 1980s exposed the monument’s basic layout. When Yondri began his work in the late 1990s, he hoped to create a detailed map of the site and identify evidence that could establish when it was built.

Yondri and his team dug at dozens of locations across the terraces and made several discoveries. First, at the foot of Terrace 1, they found a stone well fed by spring water that may have been used in ceremonies conducted at Gunung Padang when it was an active temple. Under a retaining wall on Terrace 1, Yondri recovered a piece of charcoal that has been radiocarbon dated to around 117 B.C. The dates of other charcoal samples the team found under Terrace 2 and Terrace 4 clustered around 50 B.C. “From these dates, we can assume that the terraces at Gunung Padang were not built by one generation,” says Yondri, who believes the temple was likely in use for many hundreds of years.

The team found no animal bones that would have been evidence of feasting at the site, though they did unearth examples of pottery, as well as a grinding stone that suggests food was prepared there. Whatever rituals people practiced, they left little evidence of them behind. Where the people who came to Gunung Padang to worship lived is also largely unknown. Archaeologists have found few traces of settlements near the site. Scholars are certain, however, that by the fifth century A.D., those who honored their ancestors atop Gunung Padang would have been in contact with Taruma, the earliest Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Indonesia.

In the early first millennium A.D., as merchants sailing the Maritime Silk Road between India and China traversed the Strait of Malacca, they brought with them not only great wealth but also the Hindu and Buddhist faiths, which spread along the coasts of modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia. Sanskrit stone inscriptions dating to about A.D. 450 found near the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, show that some people on the northern coast of Java had converted to Hinduism by that time. Researchers believe that the Kingdom of Taruma ruled the northern coast of Java from about A.D. 380 to 669. At that point it was absorbed into the growing Buddhist Srivijaya Empire (ca. A.D. 600–1200), which controlled the lucrative maritime trade for several more centuries.

Many scholars believe that the punden berundak on Java largely date to the period when Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms were flourishing thanks to the influx of resources brought via the Maritime Silk Road. Merchants would have traded iron goods and textiles from India and China for gold and precious wood supplied by the peoples of interior Java. It’s possible that construction and maintenance of megalithic sites such as Gunung Padang were enabled by the new levels of prosperity among inland peoples resulting from this trade. Two other substantial megalithic sites constructed in this period are Cipari, which is made up of two large stone tombs next to two stone circles about 20 feet in diameter, and Pangguyangan, a pyramidal temple consisting of seven terraces, which now has an Islamic burial at its top. “Gunung Padang doesn’t stand alone,” says Simanjuntak, “but together with other sites provides an understanding of the journey of megalithic culture in the archipelago.”

Until Islam spread to the interior of Java in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, leaders of highland clans used their wealth to mobilize their followers and recruit people from other clans to build megalithic monuments during festivals. At these days-long events, goods were redistributed among many communities. These gifts bound people together in complicated webs of obligation that shored up the social order. Though these festivals faded away once people converted to Islam, archaeologists believe they were similar to celebrations that are still held in remote regions of Indonesia.

In the seventeenth century, English and Portuguese merchants began trading for spices and enslaved people with the inhabitants of parts of islands such as Sumba and Sumatra where Islam had not yet taken hold. As these islanders’ resources began to grow, they, like earlier people on Java, began to build megalithic structures to mark the graves of honored ancestors. Archaeologist Dominik Bonatz of the Free University of Berlin has conducted research on Sumatra and is building a database of the island’s estimated 1,500 megalithic sites. He has relied in large part on traditional stories to reconstruct the history of sites built from the early seventeenth century until the present. He possesses a uniquely helpful resource: the records of nineteenth-century missionaries who collected information from local people about the sites. Today, he says, people can still recall traditions associated with certain megaliths going back more than 15 generations, noting that their recollections match the stories collected by the missionaries. “They have a remarkably accurate memory of these sites,” says Bonatz. “Monuments constructed three hundred years ago still have very real meaning to them.”

On the island of Sumba, archaeologist Ron Adams of Willamette Cultural Resources has studied how people conduct a ceremony known as tarik batu, or “pulling the rock.” This ritual involves acquiring stones from local quarries and dragging them to cemeteries where they are used to construct mortuary megaliths. He says islanders who have the means save for their entire lives to pay for monumental tombs built during what anthropologists call feasts of merit. During these multiday festivals, as many as 1,000 people from related clans gather to haul stones weighing several tons. They also enjoy music, dancing, and feasts, all underwritten by the family or even a single individual who wishes to honor a relative or themselves. “Many of these tombs are built during the occupant’s lifetime,” says Adams. “It’s the fulfillment of a life’s dream for many.” He has observed feasts that involved slaughtering 100 pigs and 10 water buffalo—a considerable expense—during the construction of some the largest tombs on Sumba.

Archaeologist Tara Steimer-Herbet of the University of Geneva, who has excavated megalithic sites in the Near East for many years, has also observed tarik batu on Sumba. She says experiencing the songs and dancing and seeing expensive textiles draped over stones during the ritual led her to think differently about the prehistoric structures she has studied throughout her career. “They aren’t just these mute monuments,” says Steimer-Herbet. “They were erected during what must have been massive parties that were meaningful not just for the people who participated in them, but also for their descendants.” Just as they do on Sumatra and Sumba today, prehistoric megalithic monuments in the Near East and across the ancient world likely reminded people of the ancestors they honored and the rituals surrounding their construction.

The most sacred rites at Gunung Padang were conducted, Yondri believes, atop Terrace 5, the highest and smallest of the terraces. While it’s impossible to directly compare present-day Indonesian megalithic traditions with those practiced by the people who built and worshipped at Gunung Padang, modern rituals offer a glimpse of both the immense labor required to build megalithic structures and the sense of shared joy that those who erected the stones must have experienced. It’s possible to imagine those people descending the steps from the highest terrace to the lowest, where they rang the stone lute before leaving the temple and returning to their daily lives. They would have done so certain in the knowledge that their ancestors were watching over them.

Slideshow: Indonesia’s Rituals of Stone

Large stone structures and sculptures known as megaliths were built by ancient cultures across the world. Scholars will never know the precise reasons why Neolithic people in southern Britain first came together to build Stonehenge around 3000 B.C, or what motivated the inhabitants of Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, to carve their majestic moai. Today, many people living on the islands of the Indonesian archipelago still carry out rituals surrounding the creation of modern megaliths. They have many insights to offer archaeologists seeking to understand why the people of the past invested so much time and energy in building similar monuments. Archaeologist Dominik Bonatz of the Free University of Berlin has a long-running project on the island of Sumatra dedicated to excavating and recording megaliths that people living there still remember and revere. Meanwhile, on the island of Sumba, lavish ritual celebrations linked to the creation of megalithic tombs continue to draw the focus of archaeologists who seek to understand the role megaliths played in the lives of people who lived thousands of years ago.