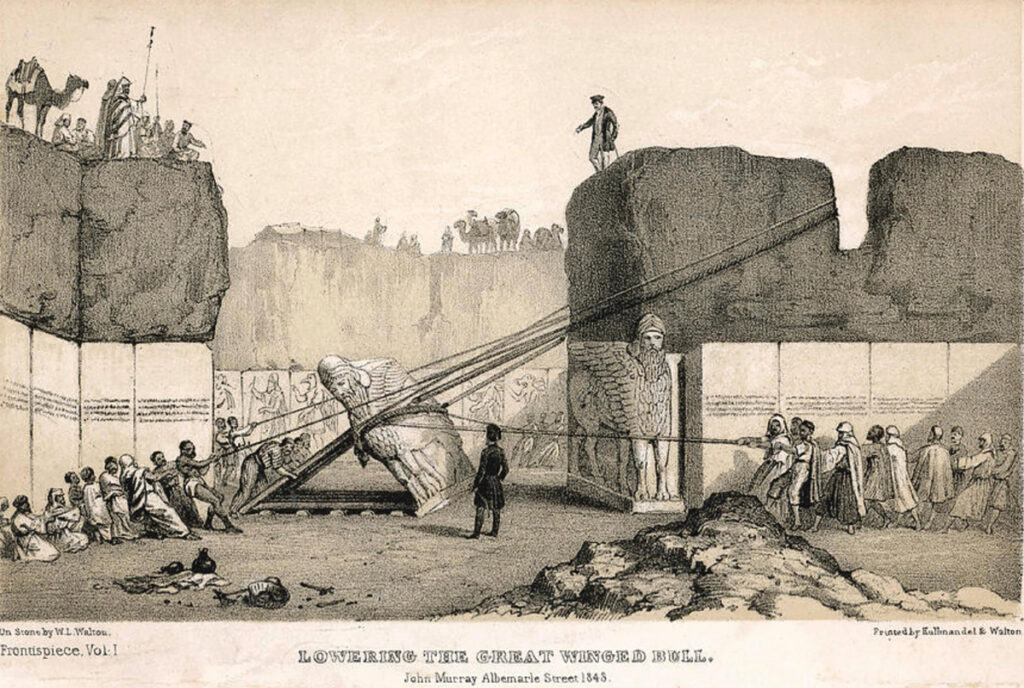

Archaeologists didn’t know what to expect when they began searching for a 2,700-year-old Assyrian sculpture that had last been seen decades before. First documented in the nineteenth century and excavated in the early 1990s, the massive statue was subsequently reburied to protect it from turmoil in northern Iraq that threatened the site. By 2023, the political situation in the region had stabilized, allowing archaeologists to return. As an Iraqi-French team removed 30 feet of debris, the figure’s fine details gradually reemerged. There were rows of delicately overlapping feathers, the hanging curls of a man’s beard, and the cloven hooves of a bull, all skillfully carved from shining white alabaster. The sculpture, which stood 12.5 feet tall and weighed nearly 20 tons, represented a lamassu, an Assyrian deity with a human head and a winged bull’s body. Given the intense events that had occurred around the site, it was a marvel that the sculpture remained in such good condition. “The lamassu had vanished between anti-tank trenches and bunkers,” says Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University archaeologist Pascal Butterlin. “Considering this situation, with traces of heavy bombing and fights all around, it’s a miracle that it wasn’t further damaged.” Only the statue’s head was missing, but Iraqi officials knew it had been surreptitiously looted in 1995 and broken into parts to be smuggled out of the country. The pieces of the lamassu’s head were successfully retrieved and are currently exhibited in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

The lamassu once stood as a protective guardian at a gate into the ancient city of Dur-Sharrukin, near modern Khorsabad. Dur-Sharrukin was intended to be the greatest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which, in the late eighth century B.C., became the largest the world had known. The city was built by Sargon II (reigned 721–705 B.C.)—the name Dur-Sharrukin means “fortress of Sargon”—to be the new capital of his flourishing kingdom. The king constructed lavish palaces, ornate temples, and mighty defensive walls. His splendid city, however, was short-lived. In 705 B.C., just a decade after he founded Dur-Sharrukin, while the city was still being built, Sargon died on the battlefield. His son Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 B.C.) inherited the throne and soon abandoned his father’s project.

Throughout their history, which goes back to around 2600 B.C., the Assyrians had built a succession of capital cities, beginning with Ashur, then Kalkhu, the ancient name for Nimrud, and then Dur-Sharrukin. After his father’s death, Sennacherib resolved to create yet another new capital. “Sargon II dies ignominiously in battle and so Khorsabad is considered a bad luck place, and his son is having none of this,” says archaeologist Michael Danti of the University of Pennsylvania. Sennacherib would follow in his father’s footsteps as a builder. In the new capital, which was located 10 miles south of Dur-Sharrukin and was twice as large, the palaces were even bigger, the artwork grander, and the walls taller. In the Old Testament, it was a notorious place of avarice and indulgence. In Greek and Roman sources, it was described as a legendary site of unparalleled size and riches. This was Nineveh.

Archaeologists rediscovered Nineveh in the nineteenth century and embarked on excavations of the site that would continue for 150 years. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, however, archaeological activity had ceased. Located on the east bank of the Tigris River near modern Mosul, Nineveh, like Dur-Sharrukin, has suffered catastrophic damage from modern warfare and vandalism, especially when Mosul was occupied by the Islamic State between 2014 and 2016. Parts of the site and its monuments were even purposely razed by bulldozers. It is also threatened by urban sprawl that is encroaching on the ancient city. In 2010, a report released by the Global Heritage Fund, a cultural watchdog, warned that Nineveh was on the verge of being irretrievably lost. As the political situation has calmed in recent years, however, an archaeological resurgence has occurred, and several international research projects have joined forces with the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH). “Things have just kind of come together, where there is access again and the opportunity for international expeditions to partner with the Iraqis,” says Danti. “We’re all finding incredible stuff. It’s a real renaissance of exploration.”

As director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Iraq Heritage Stabilization Program, Danti is seeking to mitigate the effects of the recent conflicts and to help conserve damaged sites. “It has really just been one tragedy after another for the cultural heritage of Iraq,” he says. His Iraqi-American team has recently assessed Nineveh’s iconic Mashki Gate, one of the largest of the gates that once loomed over the formidable city walls. Originally destroyed in 612 B.C. by Nineveh’s enemies, the Mashki Gate was reconstructed by Iraqi authorities in the 1970s. It was demolished again in 2016, along with the Adad Gate and parts of the walls, this time by modern hands. Currently, Danti’s team is working to reconstruct the gate once more. As part of this process, they have conducted new excavations that have involved removing a huge amount of debris. “We’re digging down deeper than previous excavations and excavating rooms that were never explored,” says Danti. In one such room, the team discovered a series of reused carved panels that represent some of the finest Assyrian artwork found in the city for a century. The panels date to the reign of Sennacherib and were likely commissioned to be displayed in what the king called his “Palace Without Rival.” Sennacherib, like other Assyrian rulers, documented his accomplishments, in both textual and figurative form, and the newly uncovered reliefs seem to depict the ruler’s military campaign in 701 B.C. against the Kingdom of Judah, an event recorded in the Bible. They attest to a time when the Neo-Assyrians were one of the richest, fiercest, and most powerful people in the world, and are reminders of an era when Nineveh was the jewel of their empire. The reliefs are just one example of the extraordinary finds that have surfaced during renewed archaeological work at the site and in its environs.

The Assyrian civilization derives its name from Ashur, the name of both their first city and their principal deity. For centuries, the Assyrians’ fortunes ebbed and flowed. But early in the first millennium B.C., a series of formidable kings ushered in a prolonged period of prosperity and expansion. What had once been a relatively insignificant city-state came to control all of Mesopotamia, as well as parts of Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia, and Arabia.

The Neo-Assyrians built their empire by relying on a trait that would make them notorious not only among their contemporaries, but even up to the present day. “All empires depend upon at least a threat of violence, but the Assyrians are particularly bloodthirsty,” Danti says. “If you rebel against them, they might burn your city down, take away your population, and execute your military leaders. If you sign a treaty with the Assyrians and break it, they annihilate you most of the time. Even by ancient standards, it’s pretty brutal.” But along with their military might, the Neo-Assyrians were renowned for their finely crafted sculptures and reliefs, their collection of literature and scientific knowledge, and the opulence of their cities. This was especially true of Nineveh.

Although excavators have found that people have lived in the area of Nineveh for at least 9,000 years, Sennacherib utterly transformed the settlement. Monumental architecture, inscriptions, and tablets all provide evidence of what the city once looked like. It had one of the ancient world’s most imposing defensive walls, which measured more than 100 feet tall and 100 feet wide in places and encircled an area of about three square miles, more than twice the size of New York City’s Central Park. These walls had at least 18 gates, one flanked with giant lamassu statues similar to the one recently rediscovered in Khorsabad. There were two large tells, or acropolises. The larger of these, known as Tell Kuyunjik, still rises 130 feet above the surrounding plain and once featured administrative buildings, luxurious palaces, and imposing temples. The city had grand houses with courtyards, broad processional streets, archives, and carved statues and reliefs. It also contained lush gardens, parks, and even menageries of exotic plants and animals captured in the far-flung reaches of the Assyrians’ territory. “The idea is that these gardens serve as a microcosm of all of the wonders of the empire, so that the people living back in the imperial capital can see just how great the empire is,” says Danti. “It would have been incredibly impressive.”

A century after Sennacherib took the throne, his capital—and indeed the Neo-Assyrian Empire—was gone. Nineveh was sacked in 612 B.C. by a coalition of Babylonians from the south and Medes from the east, two long-standing enemies and former subjects of the Assyrians. It was an event from which the Assyrians would never fully recover, and both they and Nineveh slipped into relative obscurity. The city’s exact location would remain largely unknown until the nineteenth century when the site gained worldwide attention after European archaeologists began to explore its rumored position. They soon unearthed sprawling buildings, massive statues, and more than 30,000 inscribed cuneiform tablets collected by Sennacherib’s grandson Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 B.C.), who established one of the ancient world’s greatest libraries (see “Royal Bibliophile.”). These early excavations showed that the Neo-Assyrians were far more than their reputation for warmongering and greed had led people to believe. Nineveh had been a place of wonder. When archaeological exploration came to a stop in the late twentieth century, reports of damage began to spread, and archaeologists feared that Nineveh was in danger of being lost once again.

Nineveh’s Adad Gate, which is located along one of Mosul’s main roads, has stood as perhaps the most visible symbol of the ancient city’s past glory. And, as it lay partially in ruins after it was bulldozed in 2016 by the Islamic State, it served as a reminder of the site’s calamitous recent history. Today, archaeologists have restored the gate in an effort that has become emblematic of Nineveh’s archaeological revival. “Whoever used to drive by there would have been familiar with the gate and the Assyrian city walls,” says University of Bologna archaeologist Nicolò Marchetti. “And now they can see that things are changing quickly.” Residents and tourists alike can walk in the Assyrians’ footsteps on a path that leads through the gate and winds its way across the ancient city. The path is part of a new archaeological park that includes a visitors’ center and walkways with informational signs about Nineveh’s history. This is one of very few such parks to be opened in Iraq, and it exists thanks to the efforts of Iraqi and Italian authorities and the University of Bologna’s KALAM project, named after an ancient Sumerian word meaning “country,” which seeks to protect archaeological landscapes in Iraq.

In 2019, SBAH reached out to Marchetti, who is director of the Iraqi-Italian expedition at Nineveh and KALAM’s project coordinator. “They told us Nineveh was greatly endangered and asked if we could help,” Marchetti says. “Nineveh was then, and still is now, in peril, so we felt that we had a duty.” Over the past five field seasons, the expedition has explored the history of the ancient city, attempted to preserve what remains, and assessed how much damage the site has suffered over the years. They have primarily been working in areas of the site that were heavily disturbed, such as the Adad Gate. When they began, Marchetti’s team had no idea of the condition of the gate’s original 30-foot-high mudbrick arch, one of the most notable features in ancient Nineveh. As they maneuvered a crane to remove the tons of rubble blanketing the gate, they saw that the arch had somehow survived. “We exposed the whole thing, which was completely unexpected and also very lucky,” says Marchetti, whose team installed a shelter to protect the arch.

While historically most of the archaeological attention in Nineveh has been directed at the site’s monumental structures, archaeologists from the Iraqi-Italian project have taken the opportunity to look beyond these grand edifices. They are focusing instead on unknown aspects of the city, and even on factors as fundamental as how Nineveh was planned. “Until now, research has basically been limited to some of the fortifications, and of course the acropolis with the royal palaces,” says Marchetti, “but nobody knew how this huge imperial capital was organized.”

EXPAND

ROYAL BIBLIOPHILE

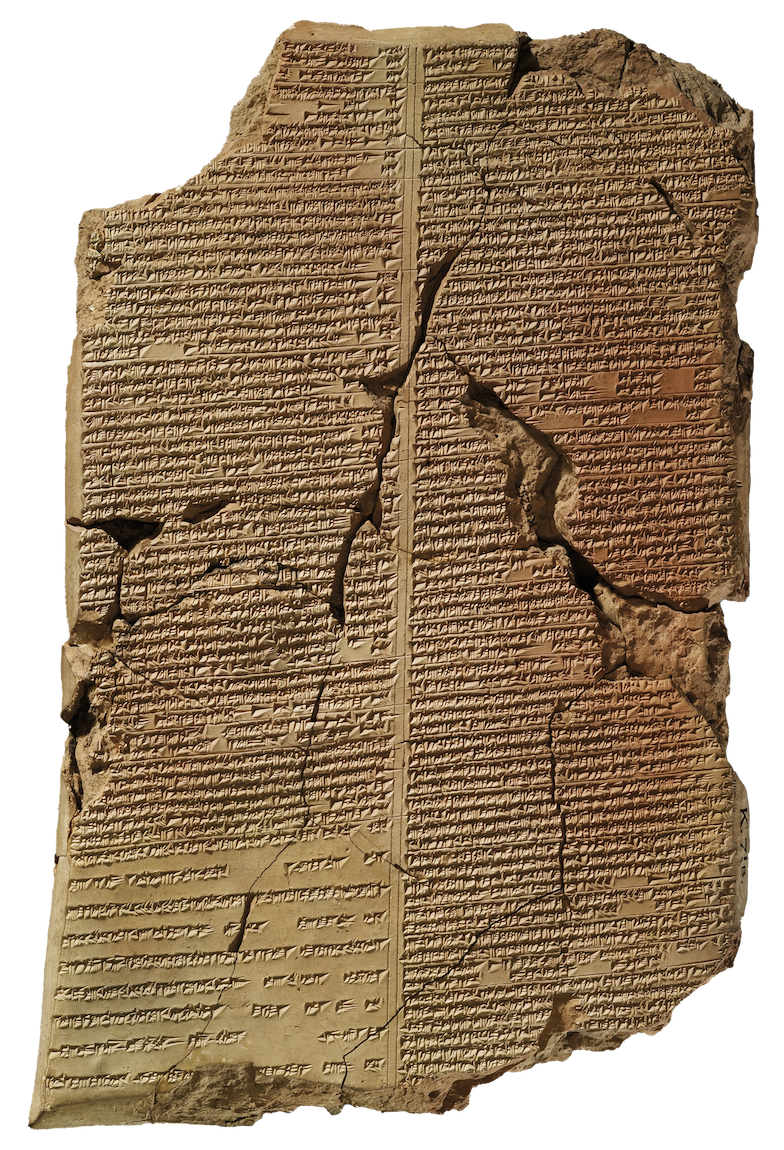

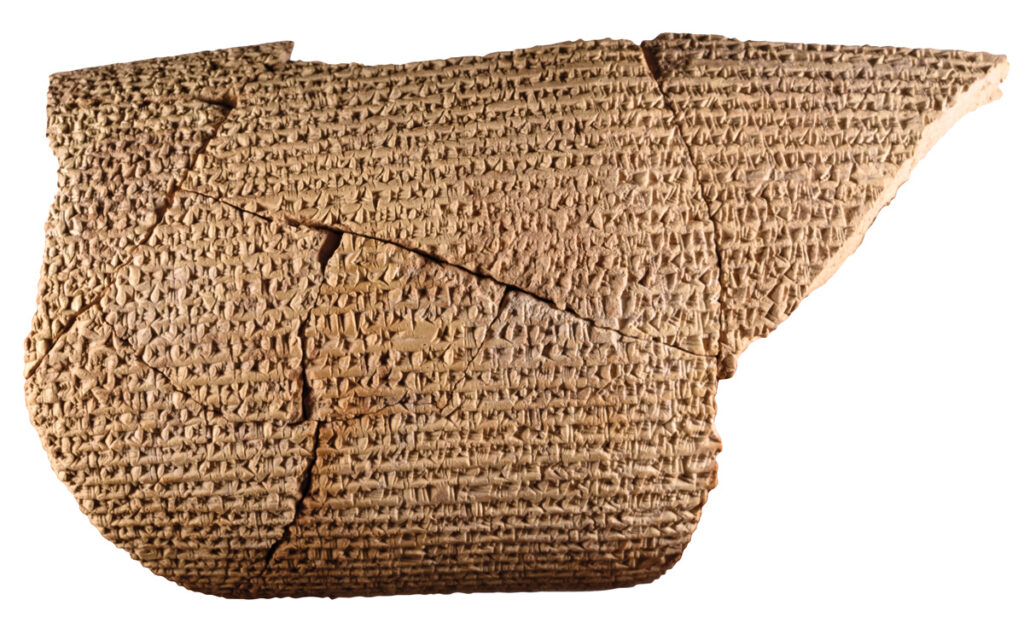

While working at the newly rediscovered site of Nineveh in northern Iraq in 1850, a team directed by Assyriologist Austen Henry Layard was exploring the ruins of a Neo-Assyrian (ca. 883–609 B.C.) palace built sometime after 700 b.c. when they came across rooms filled with thousands of clay tablets piled more than a foot high. The tablets were inscribed with the small wedge-shaped symbols known as cuneiform writing. They belonged to a library once located on the palace’s upper floor, which had come crashing down when the complex was ransacked and burned in 612 B.C. Rather than destroying the tablets, however, the fire baked, hardened, and preserved them.

This collection of written works was assembled from around the empire by Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 B.C.), who was both a formidable military leader and an avid scholar. Texts that document the king’s life boast of his education and the depth of his knowledge. He even commissioned relief sculptures that portray him with writing styluses tucked into his belt. These implements were used to create cuneiform tablets and were symbols of Ashurbanipal’s erudition. “There have always been collections of texts, going back millennia, but what is different about Ashurbanipal is quite how much he’s got,” says curator Jonathan Taylor of the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum. “He seems to have wanted to collect a copy of everything.”

Between the 1850s and 1930s, around 32,000 clay tablets from the library were uncovered. Among them were official documents such as foreign correspondence and administrative records, literary texts including the ancient Mesopotamian poem the Epic of Gilgamesh, and various other works on subjects ranging from astronomy to warfare. Ashurbanipal was particularly interested in collecting texts about divination and how to read omens and communicate with the gods. “The majority of the material there has to do with predicting the future,” says Taylor. “Portent was the ancient equivalent of science, and what the king is collecting has very much to do with power and controlling the empire.”

Archaeologists also found an assemblage of 50 tablets that researchers have only recently realized compose a medical reference manual. Known as the Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia, it is the oldest systematically organized medical handbook in the world. The compendium contains information about common bodily ailments, listed from head to toe, and provides diagnostic descriptions of each affliction and instructions on how to cure it. This sometimes involves mixing different plants together to create a potion or a salve. For example, one method of curing a headache instructs:

Crush and sieve together kukru[an aromatic], burashu [juniper], nikiptu [spurge], kammantu [plant seed], sea algae, and ballukku [an aromatic]. You boil down the mixture in beer, you shave his head, and you put it on as a bandage; then he will recover.

Other ailments require supernatural remedies conjured by reciting magical incantations and appealing to Assyrian gods for help, such as this cure for an eye injury:

If a man constantly sees a flash of light, he should say three times as follows: “I belong to Enlil and Ninlil, I belong to Ishtar and Nanaya.” He says this, then he should recover.

While the texts of Ashurbanipal’s library have been crucial in providing a deeper understanding of Neo-Assyrian life 2,700 years ago—before the library was discovered, most knowledge about the Neo-Assyrians came from the Old Testament or classical sources—there is still much that researchers hope to learn. The vast majority of the tablets remain untranslated. Most were found broken and mixed together, making it very difficult to reassemble them properly. “It’s not only like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, it’s like assembling 5,000 jigsaw puzzles simultaneously that someone has knocked off the shelf and the pieces have all scattered,” Taylor says. “We don’t have the box anymore, so we don’t even know what the picture is supposed to look like. It’s a real challenge.”

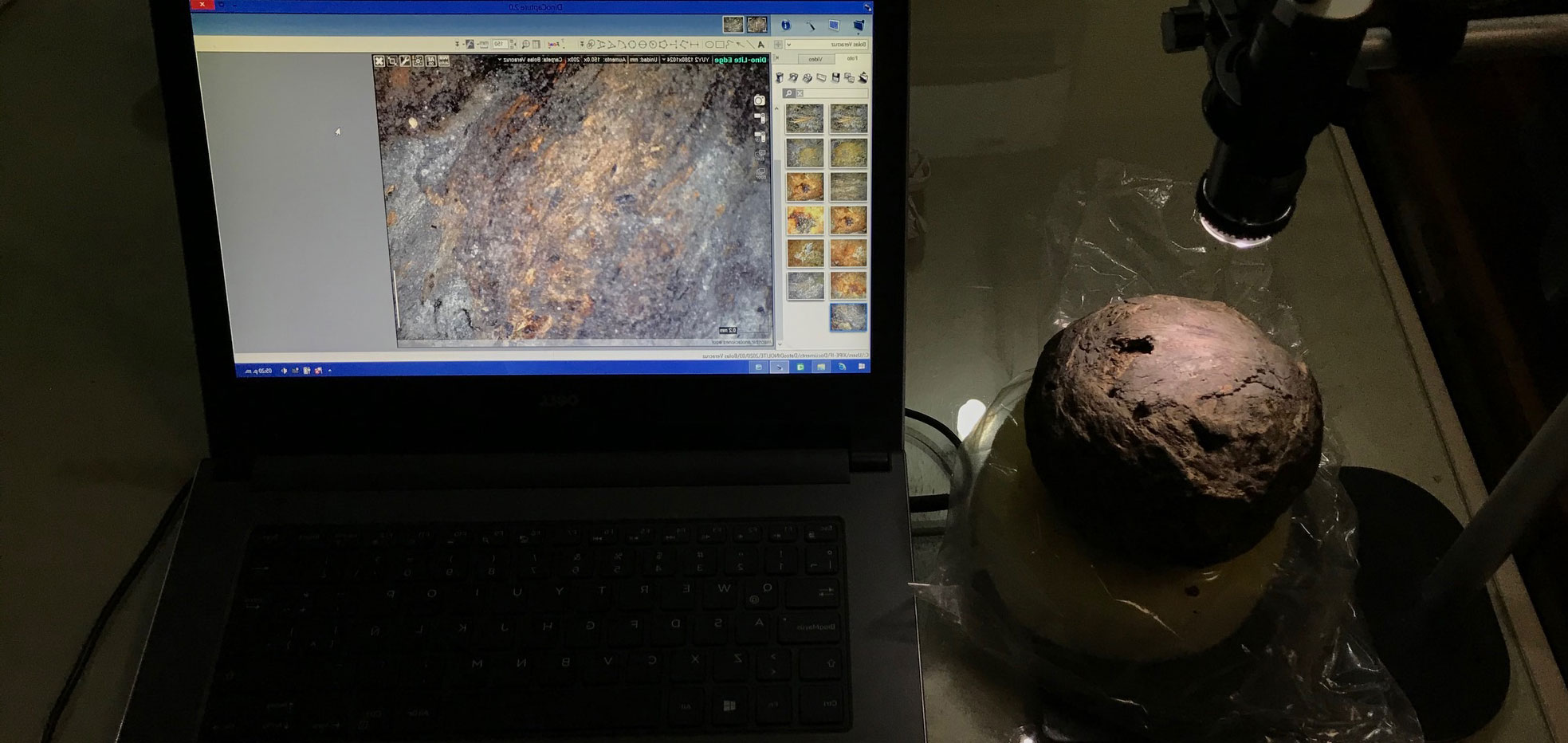

Over the last 170 years, only about 35 texts on average have been successfully pieced back together and translated each year. At that rate, it would take 400 more years to decipher Ashurbanipal’s entire library. However, imaging technology and artificial intelligence are speeding things up and making the process much more efficient. “Now that we have the resources,” Taylor says, “you can imagine easily that within a generation we will have solved a centuries-long problem.”

Perhaps the most surprising revelation has been how densely occupied Nineveh truly was. Scholars had assumed that swaths of the city within the walls were dedicated to open spaces, gardens, and pasturelands, especially in the northeast corner, where few archaeological features were visible on the surface. However, geophysical surveys have indicated quite the opposite. “They revealed a very packed situation with houses and narrow alleys—there is not a single empty square meter,” Marchetti says. “Prior to our work, Nineveh was thought to have had large empty areas, but there is nothing of the kind.”

Marchetti’s team, which has mainly limited its investigations to compromised areas of the site, such as those adjacent to a six-lane road that was intentionally dug through the ancient city by the Islamic State, has now excavated in more than 20 new locations. “We’re mainly working to save whatever we can from the current situation,” Marchetti says. This has led to the discovery of a wide array of residential properties, ranging from humble abodes to sumptuous villas with expansive courtyards. The researchers have found evidence of administrative and economic activities in the form of cylinder seals, amulets, and tokens, as well as financial transactions recorded in cuneiform on clay tablets. One spectacular discovery was a house belonging to a baru, or “diviner,” who specialized in reading omens and interpreting the will of the gods. Archaeologists found piles of inscribed texts buried within the property related to the baru’s practice. There are incantations and literary texts, including a copy of an epic poem known as the Lugal-e, which recounts the exploits of the Mesopotamian warrior god Ninurta. The excavations have also uncovered the most complete description ever found of a mysterious ceremony known as the Mis-Pi. During this ritual, incantations were performed around a newly created statue of an Assyrian deity, allowing the spirit of the god to inhabit the statue and bring it to life. “It’s an incredibly important ritual, and although it is well-known, there were huge lacunae,” Marchetti says. “These texts now allow our philological team to fill in these gaps. It was an unexpected and beautiful discovery.”

The baru’s cuneiform tablets were not the only cache the team uncovered. In a small palace near the Adad Gate, they excavated an area believed to be a scriptorium. One room contained a large block of clay and a writing stylus, while an adjacent room had benches where researchers believe that texts were created and copied. Further investigation nearby revealed more than 200 inscribed clay tablets that included magical incantations and descriptions of omens, as well as literary and medical texts. “What’s especially interesting is that most of them aren’t duplicates, but are texts that were unknown until now,” Marchetti says. “It’s a unique find that is the most important epigraphic discovery at Nineveh after Ashurbanipal’s library.”

During excavations near the city’s eastern wall, Marchetti’s team even discovered a previously unknown gate, along with evidence of the Neo-Assyrians’ skill as hydraulic engineers. There, they unearthed a 135-foot-long water tunnel that passed directly through a section of the 100-foot-thick defensive wall. The conduit brought water from the nearby Khosr River into the city and is just one small part of the sophisticated water system the Neo-Assyrians developed to support a city the size of Nineveh. This hydraulic network began more than 40 miles away, in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, where archaeologists are continuing to make intriguing discoveries.

While other projects have concentrated on the core of the city and its immediate surroundings, archaeologists from the University of Udine, in collaboration with Kurdish and Iraqi authorities, have made the hinterland of the great Neo-Assyrian capital their focus. Scholars working with a wide-ranging multidisciplinary venture called the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project (LoNAP) are investigating 1,200 square miles of terrain in the Duhok region of Iraqi Kurdistan, the first extensive fieldwork that has taken place in the area in nearly a century. They are learning that just as the Assyrian capitals grew exponentially in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., so did the population of the surrounding countryside. And, for the first time, researchers are arriving at a better understanding of the extensive water supply system engineered by Sennacherib to support both urban and rural settlements. Over the course of just 15 years, between 703 and 688 B.C., Sennacherib constructed more than 200 miles of canals, weirs, dams, tunnels, and reservoirs. Channels were dug through bedrock, rivers diverted, natural springs enlarged, and aqueducts erected. “These are the first known stone aqueducts in history and predate the Roman ones by roughly four centuries,” says University of Udine archaeologist Daniele Morandi Bonacossi, who is codirector of LoNAP.

While digging near the village of Faida, Morandi Bonacossi’s team brought to light a rare set of reliefs—the first of their kind to be fully excavated in nearly two centuries—carved into the side of a rock-cut canal. These reliefs were first identified in the 1970s and later investigated by Morandi Bonacossi beginning in 2012. Yet, as happened in so much of the land in and around Nineveh, recent events brought the work to a halt. The team has now completed the excavation of the canal. “The security situation in the area led to the postponement of the beginning of our archaeological project at the site,” says Morandi Bonacossi. “But in 2019, together with the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage, we launched a rescue project aimed at salvaging the canal and its rock reliefs. The true extent of the Assyrians’ sculptural program only became clear forty years after its first partial discovery.”

The channel’s 13 carved panels each measures more than six feet high and 15 feet wide, and are spread out over at least a mile. Each panel depicts a cultic scene involving a procession of statues of the seven principal Assyrian deities—Ashur, Mullissu, Sin, Nabu, Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar—standing atop striding animals. At either end of the parade of deities, there are images of a king, probably Sennacherib, who had the artwork commissioned to commemorate his achievement in constructing the canal. Morandi Bonacossi believes that there are almost certainly other rock-cut reliefs along the six-mile canal but is content to leave them buried, where they are safe from harm. “It’s always a good idea not to exhaust an archaeological site,” he says, “so that other generations who will operate with new methods and technological instruments can check and improve our understanding.”

Nineveh’s ultimate demise at the hands of the Babylonians and the Medes was exceptionally violent, perhaps payback for the treatment they had suffered as subjects of the Neo-Assyrians. “It’s not about just defeating the Assyrians,” says Danti. “They want to stamp them out so that they can never rise from the ashes again.” Evidence of this catastrophic engagement is ubiquitous around the city, especially within Nineveh’s Halzi Gate, where parts of the population came to either defend the city or to flee it. “There, as at other areas, we found bodies of women, children, and older people killed on the spot in 612 B.C.,” says Marchetti. “The ferocity of that attack is clear. There’s a carpet of bodies that is an impressive reminder of what warfare was like at the time.”

Since 2019, archaeologists have begun to unearth evidence showing that, in fact, Nineveh was partially rebuilt in the years after its vicious destruction. But neither the city nor the Assyrians would regain their former glory. Now, as international teams once more rebuild some of Nineveh’s iconic monuments, renewed archaeological investigation is lifting the site into prominence again. The Mashki and Adad Gates will soon stand anew as tangible symbols of the region’s long history and of its archaeological renaissance. For the people of northern Iraq, it is a welcome sight. “These huge monuments and stretches of city walls became part of the urban landscape, and Mosulites are very attached to them,” says Marchetti. “People in Mosul can now see that we are there to help take care of their heritage.”