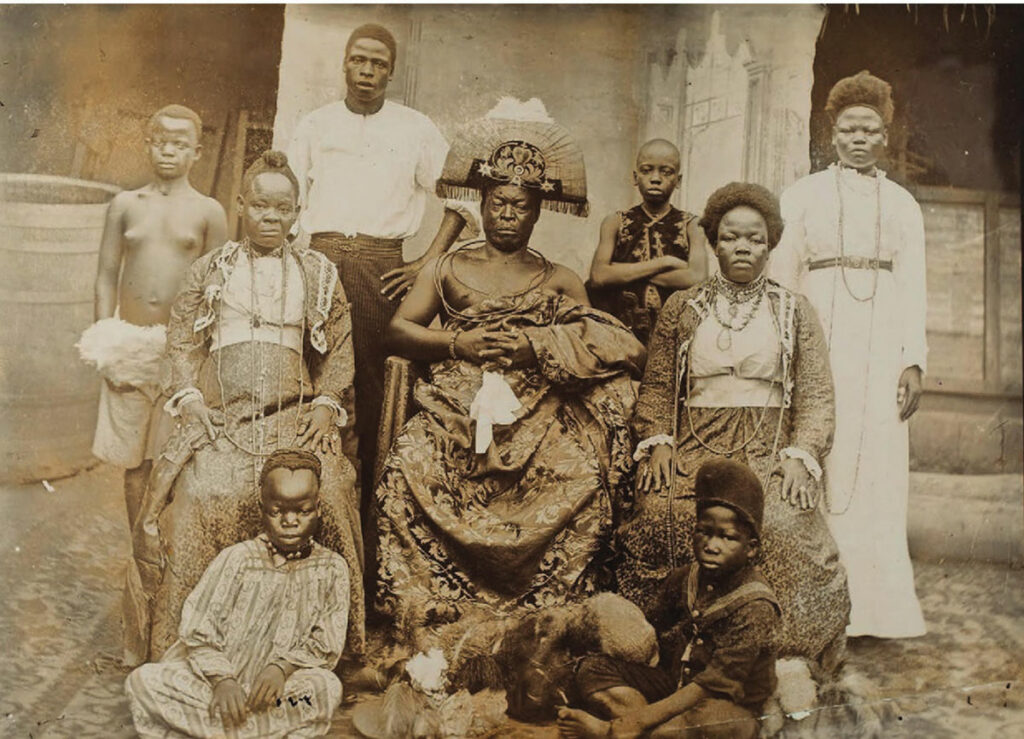

When visitors arrive at Benin Airport in southern Nigeria’s Edo State, one of the first things they see is a large poster welcoming them to the state’s capital city. It features an aerial photograph of a huge traffic circle—one of the world’s largest, authorities boast—known as Ovonramwen Square, named for the powerful oba, or king, who reigned over the Benin Kingdom from 1888 to 1897. Towering over the giant roundabout are striking bronze sculptures featuring larger-than-life-size royal figures and their attendants and, in one case, a soon-to-die warrior battling British soldiers. The statues are masterpieces of modern smithing. In a corner of the poster, in front of which travelers pose for family photos, is an image of a sixteenth-century ivory pendant mask depicting Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie (reigned ca. 1504–1550). Five nearly identical pendants, meant to be worn on a belt, are known to exist.

Ovonramwen Square is distinguished by more than its size and statues. Today it lies at the center of the low-rise city’s street network, circled by six lanes of traffic and, on a bad day, partially clogged by market stalls and pedestrians. Set among trees in a small park amid the revolving cars and trucks is the Benin City National Museum, which houses material from Nigeria’s rich array of cultures, including the Benin Kingdom. From the thirteenth to nineteenth century, Benin City, then known as Edo, was the capital of one of West Africa’s most powerful kingdoms. At the end of the twelfth century, according to oral tradition, the Edo people in what is now the center of southern Nigeria rebelled against their rulers, known as ogisos, or “kings of the sky,” and founded the Benin Kingdom. Their first oba was named Eweka.

Over the following centuries, the dynastic kingdom grew through treaties, war, and trade with regional kingdoms, cultures, and, from the fifteenth century, European powers. It further strengthened during the rule of Oba Ewuare (reigned ca. 1440–1473), when it controlled trade routes along the coast from the western Niger Delta into the modern Nigerian capital of Abuja and nearly as far as Accra in modern Ghana. In the fifteenth century, the royal houses of Benin and Portugal began to trade pepper, ivory, palm oil, gold, and later, enslaved people. Reports reached Europe of a great city with wide, straight streets led by a king who was both respected and feared. He commanded people who had carved a productive agricultural landscape out of malarial rainforest and whose artisans were as skilled as any. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the kingdom is said to have had a peak population of a million, after which its power and prestige declined significantly. Then, in 1897, it came to a sudden and brutal end.

Immediately to the south of Ovonramwen Square, archaeologists are working where the vast historic palace of the obas stood for six centuries. The palace compound, whose construction was begun by Oba Ewedo (reigned ca. 1255–1280), spread over several acres at the heart of the kingdom’s capital. There were workshops, storerooms, shrines—a nineteenth-century European visitor noted 25 or 30 royal altars—meeting halls where chiefs would gather and debate, and housing for the king’s wives and children. The city beyond the palace included quarters for groups of chiefs and officials who had responsibilities that ranged from the supervision of smiths to supplying food and servants to the oba’s household.

The first written description of the palace, by a Dutch historian in 1668, conjures royal courtyards and galleries festooned with what he referred to as cast-copper artworks featuring “deeds of war and battle scenes.” These were some of the famous Benin Bronzes, which were not made of bronze, but of brass, a copper-zinc alloy, much of it brought to the kingdom by Portuguese traders. The phrase is also used today to refer to items carved from ivory, wood, and coral. (See “The Benin Bronzes’ Secret Ingredient,” November/December 2023.) Most of the bronzes were stolen by British soldiers during the events of 1897, including the ivory pendants depicting Idia, which are now held far from Nigeria in institutions such as the British Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2022, Germany’s Linden Museum committed to Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments to return its Idia pendant.

By the 1880s, European nations had agreed that the part of coastal West Africa including what became Nigeria would be reserved for British interests. The imperial mission aimed to “civilize”—to spread Christianity and suppress the Atlantic slave trade—but also to profit from trading and establish power bases, and the British were not above using military action when they encountered resistance. In 1897, a newly arrived coastal administrator, James Phillips, made an unauthorized trip inland to meet Oba Ovonramwen, who, feeling mistreated, had blocked the lucrative palm oil trade. Having ignored the oba’s warnings not to approach Benin City, Phillips was ambushed and killed, along with all but two of his small British party and an unknown number of local porters. In response, more than 1,000 British soldiers attacked the capital with machine guns in an expedition authorized by the British government. Occupants of the palace and surrounding quarters mostly fled into the bush or were murdered, and the palace was looted of its treasures and burned to the ground. The oba was tried and exiled far from his home to territory belonging to the Igbo people. Before long, the palace site was taken over by colonial police barracks, administrative offices, and a small European cemetery. All physical traces of the palace’s former functions disappeared, and the kingdom came under British control.

In 2022, in advance of the creation of an ambitious new campus for the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), which will include a museum, an archaeological science lab, and a contemporary art gallery, archaeologists began excavating within the site of the former palace. When MOWAA chose the location, it was dominated by barracks and police buildings, as well as others that had been vacated when a hospital and state health offices moved elsewhere in the city. Most of these structures have since been demolished, leaving a wide-open space where early colonial records and oral history suggest that, alongside meeting rooms and shrines, smiths serving generations of obas had lived and worked.

The international MOWAA Archaeology Project is a collaboration between MOWAA and the British Museum. This project is approaching construction as an opportunity to learn about the site’s heritage, a first for Nigeria on this scale. Abidemi Babalola is the project’s lead archaeologist. He was among the British Museum’s scientific staff when it sought someone for the job, and he saw a rare opportunity. “We’re working at the site of the British invasion in 1897,” he says. “I try to have a sense of the history of that landscape, both pre- and post-invasion.” Babalola is joined by Oluwadamilare Omogbai, an archaeologist with Wessex Archaeology. “I’m originally from Edo State,” Omogbai says. “This is my home, my passion.”

Excavations around the palace in the 1960s had exposed deep stratigraphy, with fragments of mud walls, brass-working crucibles, and, in an infilled well, a dozen elephant tusks and the remains of 45 people, most of them women, radiocarbon dated to the thirteenth century. The excavators’ main aim at the time—which they achieved—was to create a reference set of datable pottery that they could use to begin to understand the kingdom’s history.

The new excavation began on the site of a planned conservation and display center to be known as the Institute, which is due to open in late 2024. Researchers knew that the palace’s women’s quarters, which were off-limits to all men except the oba, had been in the vicinity. Using ground-penetrating radar, the team has identified what look like parts of the quarters’ enclosure wall and what may be associated structures. After excavating some of these underground anomalies, they followed up by digging deep trenches where water and sewage tanks were to be installed.

There, the team uncovered great quantities of artifacts, including ironwork and local pottery as well as glass drinking bottles made in Britain. Most of the bottles can be dated to between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, based on their shape or brand. Archaeologist Marcus Brittain of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit says the iron objects, including a kettle, containers, and a British Navy cutlass blade, suggest that the area once included a military field kitchen established after the 1897 attack.

But there is another dimension to the site. West African smoking pipes and handmade ceramics found there, says MOWAA archaeologist Adebayo Folorunso, are evidence of local traditions, and gin bottles—of which there were many—were often traded and then placed in Benin shrines before the British invasion. Part of the palace site’s story may be the meeting of traditional African rituals and the growing British Empire, with one ceding to the other. “You can’t see the footprint of the old palace now because of the way the city’s laid out,” says archaeologist Chris Breeden of Wessex Archaeology. “You can’t even recognize where the walls were. It feels like a deliberate colonial act.” Without looking underground, he adds, you’d have no idea the palace had ever been there.

In 2023, the team cleared an area to the west of the Institute’s future location, where the rainforest gallery, an exhibition space, will be built and a rainforest garden will be planted. They returned in April 2024, and will be back on site again later in the year, bracketing southern Nigeria’s months of monsoon-like rain while hoping to avoid the full impact of dry-season desiccation. The changing climate, however, makes conditions unpredictable, and in November 2023 occasional downpours flooded trenches and sent archaeologists to the shelter of their offices in a former hospital outbuilding, one of the few still standing. “Now you can grow big, fat sweet corn,” says Babalola, “only it’s the wrong season.”

During the kingdom’s heyday, the palace was located in the corner of an irregularly shaped enclosure about two miles long and a mile across, defined by a massive bank and ditch breached by nine gateways. The enclosure was further surrounded by an extensive network of earthworks. Oral tradition and historical accounts date the origins of these ramparts, known as the Benin City walls and moats, to around 1500. They were also described by Portuguese and later Dutch explorers. Said to have been largely built by Oba Esigie, the walls and moats served a variety of functions, from controlling the city and surrounding landscape to military defense and flood management. For the last century, people have quarried the walls for building material. The encroaching city also poses a threat to them. To draw attention to the walls’ historic significance, archaeologist Segun Opadeji, MOWAA Archaeology Project field director, is now mapping them. In one location, a car is parked against a great bank of red earth overgrown with bamboo that towers over mud-walled homes. “I take tourists to visit this area so the communities can see it is valued,” says Opadeji.

In some areas of the excavation, archaeologists found that the ground on which the palace once stood had already been leveled, whether immediately after the 1897 raid or when the twentieth-century parking lot and buildings were created. As a result, they soon began to unearth a significant number of artifacts very close to the surface—notably, groups of sherds of locally made pots decorated with finger impressions and fragments of white chalk in piles, as if debris had been swept into the corner of a room. In fact, these deposits are likely to be remnants of Benin Kingdom shrines. An example of how the shrines may once have looked can be seen elsewhere in the city, in Chief Ogiamien’s Palace, a mud-walled complex of rooms, passages, and courtyards. Said to have originally been built in 1160 by the dynasty of rulers who preceded Oba Eweka, this palace survived the British raid and was inhabited until 1975. Each shrine there, typically composed of an alcove with a low shelf filling an entire wall, is dedicated to its own deity. Collections of objects—among them ornate wooden clubs, machetes, drums, wooden staffs, cowrie shells, ox horns, animal bones, pots, and handbells—honor gods of fertility, happiness, iron, and medicine. A future archaeologist might well recognize such shrines by analyzing the artifacts and room layouts uncovered in a new excavation of the oba’s palace, but identifying their meaning may be beyond reach.

Late in 2023, while digging in the punishing heat, MOWAA archaeologist Gbenga Ekundayo found more than 100 pieces of metal scattered in the red dirt of the palace site. Among them were 40 bullet shells, a dozen Nigerian police buckles, a couple of helmet rims, knife handles, and water bottles. There were also a buckle and a button featuring the British crown. Exactly who discarded these items and why will likely never be known, but in a city proud of its long tradition of craft smithing, it’s impossible to imagine that they were unaware of the objects’ worth as scrap. Opadeji thinks they date from a time of colonial transition: Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960, but many British personnel remained in their posts after that. Ekundayo’s finds are evidence of a faded empire and of a newly independent nation. One day, perhaps, these archetypal Benin City objects will shine in a case in MOWAA’s new space, conveying a message of change and survival.

Ensuring that all the artifacts turned up by the palace excavation are cleaned, sorted, recorded, and stored is the job of MOWAA archaeologist Emmanuel Olaleye. “Objects aren’t just an end to themselves, they are a means to an end,” he says. “They speak to us: ‘Look, your fathers did this, they had a knowledge of science, of geology, of geography. They also knew where to get clay and how to make pots, and how to treat illnesses.’ If we are wise, I think we should learn from them.”

Halfway through the excavations, each of the trenches has acquired its own character, with hints of what may soon be revealed. In one, there are the tops of wall footings, some made of mudbrick in a style unlike the local tradition. These might be parts of early colonial buildings not marked on any maps. There is already deep stratigraphy in the south section of the excavation, where finds of crucibles and evidence of lead processing in the form of casting or smelting slag are a reminder that somewhere in the area were the oba’s smiths’ quarters.

There is a poignancy to being at the future location of the MOWAA campus, where the modern construction site contrasts with crumbling buildings and the odd clump of banana or fig trees. This space was once at the center of a great kingdom, and local chiefs, nineteenth-century British soldiers, oral historians, and academics have all expressed their own versions of its past. So, too, have brass objects in faraway museums from which gaze the faces of royalty, warriors, and servants, emissaries from another era. But now, in this place where the oba’s smiths worked, where his ritual specialists and chiefs once lived, and where his warriors, musicians, wives, and all the people who brought color to his palace once spent their lives, there is only one small corner where a visitor can come face to face with that past world: the European cemetery. “The MOWAA Project is incorporating a Nigeria-wide community of archaeologists and students,” Babalola says. “Excavation is beginning to reveal how the site was used for various activities in different places. There are limits to historical documentation, and archaeology can help understand deep history in Africa.”

A five-minute drive from the palace excavations is Igun Street, a heritage attraction that is remarkable for the tenacity of its tradition reaching back centuries. Much of Benin City consists of single-story shops and dwellings with rusty corrugated roofs, periodically interrupted by taller and newer-looking buildings rising above well-maintained pavement. Walking through a concrete arch painted bright red to enter Igun Street feels like stepping into another world. The street is paved with bricks, not asphalt. Stretching into the hazy distance on either side of the perfectly straight road are buildings with low brown roofs and little else. The buildings face out toward pedestrians, parked cars, and slow-moving traffic, with verandas and open shop fronts displaying their wares—red and cream coral jewelry, wood carvings, and cast brass and bronze objects. These range from ancient-looking masks to a Christ figure to a life-size leopard—the fierce cat was a symbol of power in the Benin Kingdom, and the oba was known as the leopard of the house. Behind the tourist-oriented fronts, however, is something unexpected: men casting the objects for sale.

The workshops on Igun Street are still operated by hereditary smiths, whose permission to cast is the gift of the present oba. The process they employ, known as lost wax, is also ancient. The object to be cast is first modeled precisely in wax, which is then wrapped in clay. When the clay is fired, the wax evaporates, leaving a cavity that becomes the mold into which the molten metal is poured. On a rainy day in 2023, British Museum archaeologist Sam Nixon and a group of team members went to Igun Street, where they watched skilled craftspeople in back gardens pour hot brass while wearing open-toed sandals, their hands bare. Nixon was on the hunt for a water pump, and asked Chief Inneh, hereditary leader of the brass casters’ guild, an organization said by its members to date back to the thirteenth century, where he might find one. The chief soon located a pump and before the day was out, it was heaving red, muddy water through a long pipe back at the palace site as mosquitoes buzzed under the trees and the water level in the trench slowly fell to expose the tops of excavated mud walls.

Notwithstanding the destruction of the oba’s palace and the theft of its treasures more than a century ago, Benin City retains deep roots, with skills, traditions, spoken histories, and political and family links and hierarchies reaching back to long before the attack. A new palace built by Oba Eweka II (reigned 1914–1933) early in the twentieth century still stands, just to the west of the future MOWAA campus. The present oba, Ewuare II, who has reigned since 2016, traces his ancestry to a dynasty that was founded around 1300. Ovonramwen Square’s colossal figures, which gaze across the speeding cars from their high pedestals, were cast by smiths who inherited their trade from those who made the thousands of bronzes plundered in 1897. The ongoing excavations and the museum and arts complex being built promise to both enrich those histories and empower the creativity of future generations.