Recent results from a long-term study of pottery residues has revealed that farmers in the Middle East and Europe had been using beeswax for almost as long as they had made pots—but perhaps just not extensively. The discovery was made possible because of advances in techniques for distinguishing different types of lipids, naturally occurring molecules such as fats and waxes, from each other. Of thousands of sherds studied, about 80 were found to contain beeswax, indicating that it may have been a relatively scarce material in the Neolithic period, the time when people were starting to farm and make pottery.

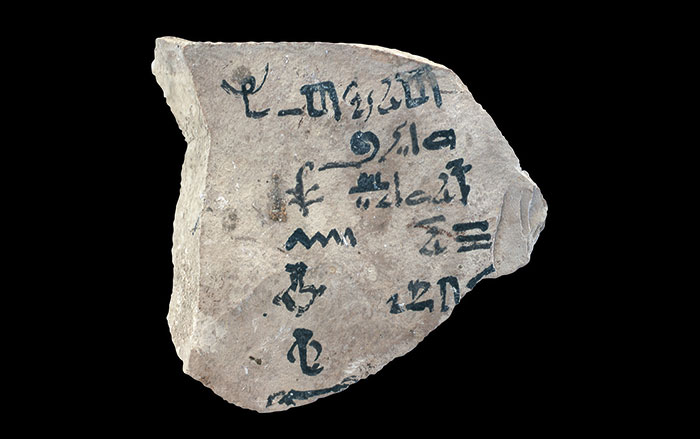

What Neolithic people were doing with the beeswax is a matter of speculation. According to Melanie Roffet-Salque, a biochemist at the University of Bristol and leader of the research group, it may have been used to waterproof the inside of pots, or may have been deposited as wax combs were melted to extract valuable honey—one of the few sweeteners available at the time. The earliest pottery sherds containing beeswax date to the seventh millennium B.C., and were found at several sites in what is now Turkey. One of these, Cayönü Tepesi, is also where the research team previously found a pottery sherd that contains the earliest evidence of milk use.

Roffet-Salque also cautions that the presence of beeswax residue on pots does not necessarily mean that early farmers were beekeepers. They may have been harvesting wild honey and wax. The first solid evidence of beekeeping appears in an Egyptian painting from 2400 B.C., but bee products clearly have a much longer history. A lump of beeswax found among other artifacts in South Africa’s Border Cave is at least 24,000 years old.

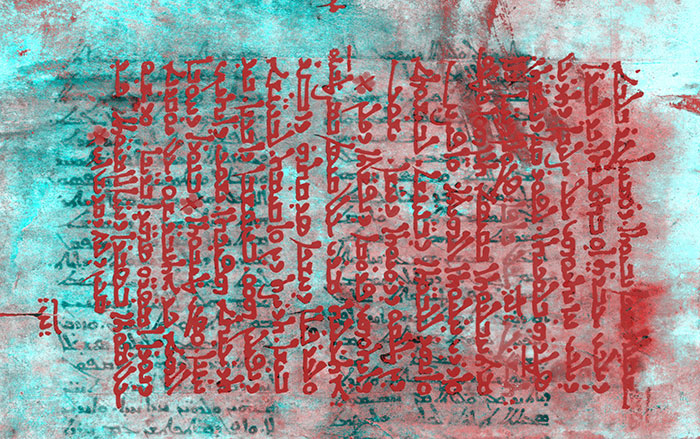

Studying pottery using this process has produced important findings about what products Neolithic people used or valued, but it has at least one drawback. “It’s very time-consuming,” says Roffet-Salque. “It’s taken us 20 years for 6,000 sherds.”