The Roman city of Arelate, today known as Arles, France, was one of the most important ports of the later Roman Empire. After siding with Julius Caesar during his civil war against Pompey, the town was formally established as a Roman colony for Caesar’s veterans in 46 or 45 B.C. Strategically located along the Rhône River in southern Gaul, Arelate developed into such a major economic, political, and cultural center that it was referred to as the “little Rome of the Gauls” by the fourth-century poet Ausonius.

Today, the city’s left bank, which served as the Roman settlement’s civic and administrative heart, is strewn with the remnants of ancient monuments: a theater, an amphitheater, baths, and a circus. It has long been thought that the city’s right bank was far less developed in the early Roman period, only witnessing significant growth decades or centuries later. However, this perception of ancient Arles is beginning to change as an ongoing investigation uncovers parts of a wealthy Roman residential area, providing new evidence of the early development of Arles’ periphery and also revealing some of the finest Roman wall paintings found anywhere in France.

A project led by the Museum of Ancient Arles is in the middle of a multiyear campaign to excavate the site of an eighteenth-century glassworks factory in the Trinquetaille district along Arles’ right bank. The glassworks complex—itself a designated historic site—was acquired by the city in the late 1970s. During the initial excavation of the property in the 1980s, archaeologists discovered a second-century A.D. Roman residential neighborhood buried beneath it, but the investigation was short-lived.

Over the past two years, a plan for rehabilitating and restoring the site has brought archaeologists back for the first time in decades. According to lead archaeologist Marie-Pierre Rothé, the renewed excavation has allowed researchers to dig deeper beneath the property and to unravel the surprisingly early history of the site. Beneath at least one Roman house discovered in the 1980s lies the much earlier foundation of an opulent Roman property dating back to the first decades of the Roman colony. Researchers know that as the new colony was incorporated into the Roman political and economic system, there was a sudden influx of wealth into the city, along with opportunities for advancement for both locals and Romans who migrated there. “One of our objectives,” says Rothé, “is to better understand the development of the Roman city of Arles during this early period in a neighborhood that was assumed to have been deserted.”

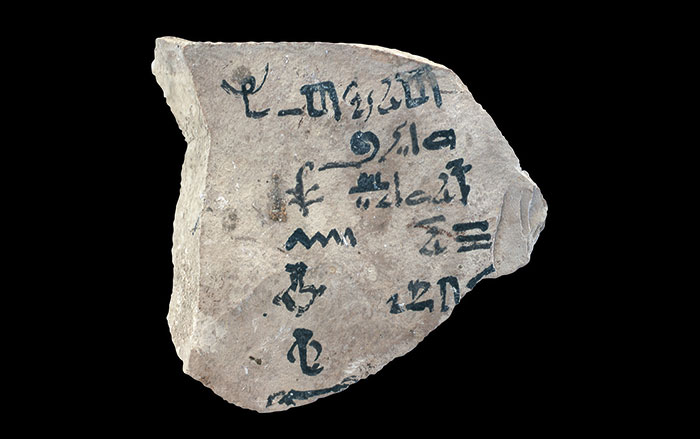

The discovery of this first-century B.C. domus, or home, is remarkable not only because it dates to a time when archaeologists believed the Trinquetaille area was void of such structures, but also for the quality of the house’s wall paintings. Its frescoes were designed in the Second Pompeian Style, according to August Mau’s nineteenth-century classification of the four major styles of Roman painting. The Second Style, which dates to between 70 and 20 B.C. in Roman Gaul, frequently used trompe l’oeil composition and painted architectural elements such as columns, windows, and marble panels to create the illusion of three-dimensional masonry. Although paintings such as these are common in Italy, especially Pompeii, they are rare in France, where only around 20 known examples exist. The excavations in Trinquetaille have uncovered the best in situ Second Style paintings in France, thanks to the preservation of a nearly five-foot-tall Roman wall to which the frescoes are still attached.

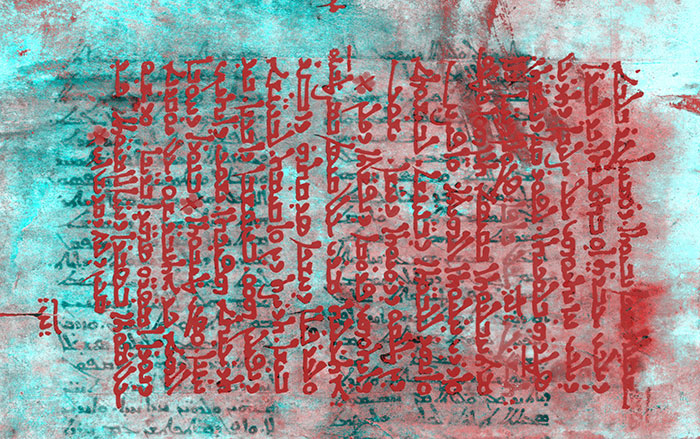

While some sections of the frescoes still remain in situ, most of the painted plaster must be retrieved from the debris and fill layers. Archaeologists now have hundreds of boxes containing thousands of fragments that need to be pieced back together like a giant jigsaw puzzle. Although this process will take years to complete, large portions of the painted ceilings and walls are already being reconstructed.

Thus far, two rooms of the first-century B.C. domus have been excavated. One is most commonly identified as a cubiculum, or bedroom. Its frescoes imitate architectural elements, such as marble paneling, Corinthian columns, podiums, and orthostats, all rendered in colors that are still vibrant. One half of the room, where the bed was likely located, shows a more luxurious design of multicolored stripes and burgundy rosettes.

The adjacent room, which served as a reception area for important guests, is decorated with large-scale figures in the Second Style. According to French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research art historian Julien Boislève, this combination is previously unknown in Gaul. One-half to three-quarter life-size figures are painted upon a bright red background, a color that was particularly expensive. “These decorations with large-scale figures are extremely rare, even in Italy, with only a half-dozen examples known,” says Boislève. “In houses like the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii or in the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Boscoreale, they mark a high level of luxury.”

For Rothé, the discovery of such a lavish late first-century B.C. house has a major impact on knowledge of the topography, urbanization, and early citizens of ancient Arles. The established notion that the right bank only developed much later is, for her, unsubstantiated. “This idea can now be swept aside since the archaeological material shows that this domus belongs to the late Republican period, and is likely to have been introduced during the creation of the colony by Caesar or even earlier,” she says. “These excavations demonstrate that development of the right bank likely happened concurrently with that of the left bank, from the time of the foundation of the Roman colony.”

Although at this stage it is not possible to identify all the painted characters, at least one female figure appears to be playing a harp-like stringed instrument. Other clues imply the presence of the god Pan, suggesting a Bacchic theme common to many Roman wall paintings. Only the most prominent families of the ancient city could have afforded a house displaying artwork of this high quality, likely created by artists brought from Italy. The house may have belonged to a wealthy Roman official who moved to Arelate in the years following its colonial founding, or perhaps it was owned by a local Arlesian aristocrat assimilating Roman culture by imitating the behavior of affluent Romans in Italy, who frequently outfitted their homes in this manner. “These paintings shed new light on the spread of Roman decorative styles after the conquest,” says Boislève. “They are unique in Gaul.”