Walk into any archaeologist’s laboratory and you’re likely to see bags of broken pottery. Walk into Bárbara Arroyo’s laboratory in a warehouse on the edge of the ruins of Kaminaljuyú in Guatemala City and you’ll find bags containing millions of pottery sherds, stacked almost to the ceiling. Millions more sit in the vaults of the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology a few miles away. Outside Arroyo’s laboratory, she and her team have dumped thousands upon thousands more ancient ceramic scraps into a large hole. “They can’t take any more at the museum,” she says with a shrug, gesturing out a window at the overflowing pit.

Long before archaeologists came to this area, visitors who had seen ancient Kaminaljuyú’s pyramids and platforms wondered what it had once been. In 1893, the British explorers Alfred and Anne Maudslay saw the city’s overgrown mounds—they mapped about 110 of them—and wrote that it must have been a “a fair-sized town” in the distant past but was now “a mere ghost town…without history or name.” In 1936, American archaeologists Edwin Shook and Alfred Kidder were amazed by the site’s “massive public buildings.” They counted more than 200 ancient structures and found that Kaminaljuyú, which means “hills of the dead” in the Mayan language K’iche’, stood at the center of an urban agglomeration that included some 35 more Maya settlements in the immediate vicinity.

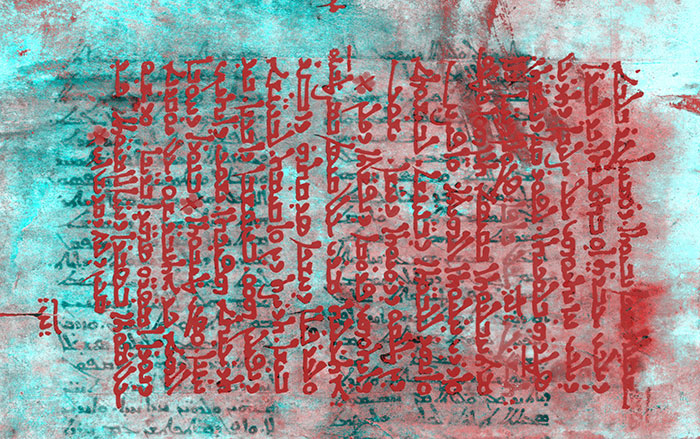

Yet what most struck Shook and Kidder, and what continues to impress archaeologists today, was the sheer quantity of ceramics they saw. The people of Kaminaljuyú made pots on an industrial scale. Excavating one burial mound, Shook and Kidder counted 7,000 sherds per cubic foot of soil and estimated that the whole mound contained the “astounding total” of 15 million fragments—the remains of some 500,000 once-intact ceramic vessels. Millions of pots were intentionally and systematically smashed by the ancient city’s own residents, or by invaders. The uncounted sherds throughout the site, excavated by Arroyo and earlier archaeologists, are physical evidence of both the city’s huge population and its turbulent history of collapse and revival.

Built alongside an ancient lake, Kaminaljuyú was once the most populous Maya city in the southern highlands. The lake dried up centuries ago, and all that’s visible of the ancient metropolis today are the grassy hills and overgrown pyramids of the Kaminaljuyú Archaeological Park, which Arroyo directs, along with a few other ancient mounds scattered around Guatemala City’s western barrios. Some of those ruins are no more than half-eroded humps, hemmed in by cinder block houses and parking lots. Others, such as the multilayered complex known as the Acropolis, where Arroyo is currently excavating, hold the remains of centuries of Maya history. “Underneath the modern city is another city that lived and died in the time of the Maya,” says Arroyo. “Not many people are aware of this, but it’s all there.

Arroyo has seen some—but not all—of the last remains of Kaminaljuyú swallowed up by urban sprawl. Some areas have been paved over for housing projects, others for shopping malls, while still others, she says, have undoubtedly been lost without anybody even knowing about them. One ancient pyramid, today a nondescript mound, sits in the garden of a private mansion. The owners of the house won’t let Arroyo look at the site, much less excavate it, so she hopes to inspect it with a drone. “It’s important to gather information about what’s left, even if you can’t dig,” she says. Nothing seems to faze her, not even the crime and blight in neighborhoods where some of Kaminaljuyú’s mounds still stand. At one, a group of homeless children have taken refuge. At another, nearby walls are covered in gang graffiti.

A few miles west, across a deep gorge, lies what used to be Naranjo, a city nearly as big as Kaminaljuyú. The early photographer Eadweard Muybridge visited Naranjo in about 1875 and photographed its ancient stone monuments, after which the site remained more or less unmolested until 2008, when it was completely paved over to make a gated community. Its houses now have whitewashed walls and red roofs like a fantasy version of a rural Spanish village. Arroyo was able to excavate and even move some of Naranjo’s monuments to a large traffic island in the middle of the new residential complex, but the rest of the site is lost forever. “Here we salvage what we can before it disappears,” she says, walking among the rescued stelas. “That’s a big part of what I do, salvage. And then it’s gone.”

About a mile south of Naranjo, Arroyo inspects a muddy vacant lot where a shopping center is soon to be built. She suspects the site might contain archaeological remains. With tractors and earthmovers grinding away nearby, she scans the ground for telltale scraps of ancient pottery. She doesn’t find any. The land may already have been so disturbed that nothing of the ancient city remains on the surface, she says.

Ruins are safe from encroachment in the Kaminaljuyú Archaeological Park, however. Although it covers less than 10 percent of the ancient city’s land area, the park is an island of tranquility among the modern capital’s congested streets, where Guatemala’s past and present mix uneasily. Under a grove of palms, shamans hold ceremonies with fire and aromatic spices, amid rings of chanting worshippers. Such rituals were violently suppressed under Guatemala’s former military regimes. Today they can attract hundreds of people. “The military said we were worshipping Satan, that we were satanic,” says the master of one ceremony, Apolinario González, who is dressed in a multicolored Indian tunic. “We are Maya and we worship as Maya,” he says. Nearby, a group of Christian evangelists walk on their knees in penitence across a lawn toward an open Bible. Under the same lawn, Arroyo once excavated the remains of two children killed in Maya sacrificial rites in about A.D. 100. Their tiny skeletons were found face down, surrounded by ceramic pots that would have contained food for the afterlife.

By digging at Kaminaljuyú’s surviving sites, Arroyo and earlier archaeologists have pieced together a thousand-year-long history of expansion and contraction, the rise and fall—and rise again—of a major city. The earliest known archaeological remains of Kaminaljuyú date from around 800 B.C. Within a few centuries, it became a trading center for salt and shells heading from the Pacific coast to the Petén lowlands, and for feathers, chocolate, and jade coming the opposite way.

Obsidian, used to make knives and axes, also contributed to the city’s early prosperity. The quarry at El Chayal, about 25 miles east, supplied raw material to the whole of the Maya realm, and its distinctive jet-black stone has been found at archaeological sites from El Salvador to the Yucatán. Arroyo has recovered thousands of chips from obsidian mined there all over Kaminaljuyú. “Most likely, the city controlled El Chayal,” she says, as one of her assistants washes a few dozen freshly excavated flakes and places them on a paper towel, each one a glistening black. “That brought great wealth to the city.

Excavations have uncovered both high-status structures and humble dwellings, suggesting that different social classes lived side by side. The city, including its ceremonial centers, was built almost entirely with adobe and timbers, unlike other Maya cities with their lofty limestone temples. “Kaminaljuyú was like New York—not the oldest city or the prettiest, but the richest,” says Liwy Grazioso, director of the Miraflores Museum, which is devoted to the history of Kaminaljuyú and built partly atop one of its mounds. “It was a great nexus of people, technology, and goods.” Kaminaljuyú continued to grow until about 400 B.C., when, for reasons archaeologists debate, cities up and down the southern Guatemalan highlands saw a sharp decline in building and population. This “Middle Preclassic collapse,” as it is known, occurred around the same time as the fall of La Venta and other Maya cities in southern Mexico, with which Kaminaljuyú had lively trade ties. But unlike those places, Kaminaljuyú came back. Within a few centuries it was again seeing explosive growth in population, but also, more ominously, heavy erosion and deforestation as the city’s growing population cut trees for fuel and dwellings.

Using its new prosperity, the city constructed a web of canals, pools, and pipes that created what Arroyo calls an “aquatic landscape,” not unlike that of the Aztecs’ lakeside capital of Tenochtitlán about 1,000 years later. The canals ranged from narrow culverts to navigable channels 30 feet wide. Residents also installed plumbing and laid clay pipes, which Arroyo has found segments of, to carry water under the streets of the ancient city. A three-mile earthen aqueduct brought fresh water into Kaminaljuyú from a spring. These waterworks were built to last. After the Spaniards arrived in the 1500s, they constructed their own aqueduct on top of the original Maya one. The whole structure snakes through Guatemala City to this day, a mound dating to more than 2,000 years ago, topped by a line of Roman-style arches.

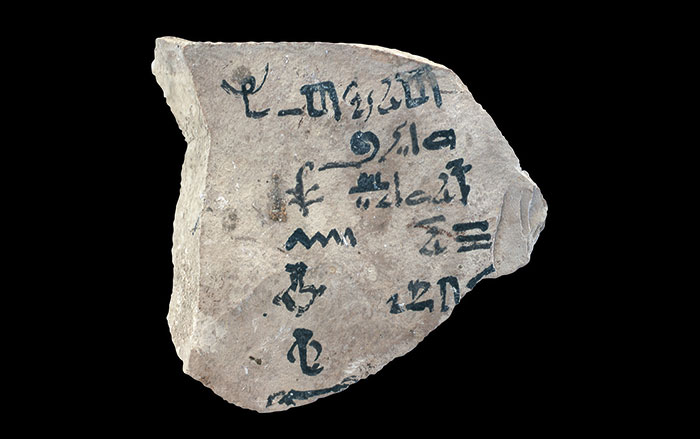

This complex system of hydraulic engineering was ultimately Kaminaljuyú’s undoing. The canals silted over and the water supply failed as the lake retreated due to drought, overuse, or both. Facing an acute water shortage, the city was again in upheaval by A.D. 150. Around that year, people deliberately chiseled away images that the city’s rulers had carved into stone monuments over centuries to mark the passage of time and to record history. They broke them and threw the pieces away like trash. Stone carvings of animals associated with water—mostly frogs and turtles—were smashed. Millions of ceramic pots were also intentionally broken and discarded. The city’s population plummeted, presumably due to mass migration.

Archaeologists speak of two possible causes for the iconoclastic spasm that hit Kaminaljuyú at this time. Federico Fahsen, a Maya epigrapher at the University of the Valley of Guatemala in Guatemala City, believes illiterate K’iche’ invaders swept in from the north, overwhelming the city’s cultured elite. “The early K’iche’ look down at this rich city in the valley, and say, ‘We want that for ourselves,’” Fahsen says, sitting in his office a short drive from the Kaminaljuyú ruins. “They enter the city, destroy the monuments, and erase the stone carvings in a frenzy of invasion and destruction.

Arroyo, however, leans toward internal upheaval as the cause of the unrest, perhaps triggered by anger over failing water supplies. There may have been other sources of resentment, too. For hundreds of years, the city’s literate elite had been using Maya script and artistic styles similar to those seen at San Bartolo, El Mirador, and other major Maya sites in the hot lowlands of northern Guatemala. After about A.D. 150, in Kaminaljuyú, those scripts and styles disappeared. They were erased from stone monuments and never employed again. It's possible," explains Arroyo, "that the destruction of monuments and broken ceramics that we're seeing were the result of a rebellion or rejection of some kind toward a governing elite that was linked by trade to the Maya lowlands. There was a return to local ways of doing things.

Judging from the quantity of new construction and ceramics being made two centuries after Kaminaljuyú’s second collapse, the city regained its population and trade ties for a time. In this period, a new cultural power also arrived in the region from the central Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacán. Exactly how Teotihuacán’s influence spread throughout the Maya realm to the south around A.D. 350—by invasion, mass migration, a shift in elite tastes, or, perhaps some combination—is poorly understood, but there was likely some movement of people. “When people from Teotihuacán arrive, they find a society still traumatized by the invasions of two centuries earlier, so the people of Kaminaljuyú easily took to the new culture,” says Sonia Medrano, a Maya specialist at Guatemala City’s University of San Carlos. A new style of architecture appeared, the talud-tablero style, typical of Mexican pyramids, with sloping walls and protruding ledges. Stone depictions of the city’s rulers also changed. No longer did they appear as supernatural beings, with jaguar fangs or bird wings, but as flesh-and-blood people. Similarly, the city’s governors no longer appeared as gods and instead became more earthly, mundane figures. All these shifts suggest less a conquest than a co-option by the Mexican cultural order, explains Arroyo. “I think what existed between Teotihuacán and Kaminaljuyú was an alliance between governing elites, a confluence of interests that allowed Kaminaljuyú to regain its trade ties and prosper again,” she says.

The new order did not last long, however. Around A.D. 700, Kaminaljuyú’s population declined once again as the Maya city of Copán, in present-day Honduras, rose in power and prestige. Kaminaljuyú was abandoned and never reoccupied, perhaps once again due to faltering water supplies. In some ways, the city’s fate foreshadowed the collapse of the wider Maya world around A.D. 900, which, say many archaeologists, may also have been triggered by widespread water shortages. Like the Maya world at large, Kaminaljuyú had its glory years before hitting hard times. Spanish conquerors made no mention of the site in their writings, and by the time Muybridge arrived, it was nothing but a vast cornfield. Only in the twentieth century did the area recover the population density it had had in antiquity, a new city once again built on top of the old.

Slideshow: A City Beneath a City

Under the streets of Guatemala’s bustling capital lies another, much older city: the Maya metropolis of Kaminaljuyú. A small sample of the ancient city’s mounds and plazas can be seen today in an “archaeological park” on Guatemala City’s north side. Since the 1930s, archaeologists have excavated pyramids, staircases, hundreds of ceremonial stone markers known as steles, and millions of ceramic sherds—all testament to a big town that waxed and waned over 1,500 years of history. Here are some scenes from the rediscovery of Kaminaljuyú.