As with many archaeological sites, the Côa Valley in northeastern Portugal came to the attention of authorities because of a dam. An energy company commissioned an archaeological survey prior to beginning construction, which led to the discovery of one of Europe’s largest open-air “museums” of Paleolithic rock art. “Petroglyphs can’t swim,” stated a campaign to protect the works. These efforts helped stop the building of the dam and ensured the survival of the Côa Valley’s heritage. UNESCO describes it as “an outstanding example of the sudden flowering of creative genius at the dawn of human cultural development.” The Côa Valley petroglyphs are comparable to the famous cave art found in other parts of Europe, says archaeologist João Zilhão of the University of Barcelona. The quantity of art in the valley suggests to him that though the cave art is more famous, it was probably less common than open-air works, many of which may have been lost to weathering.

THE SITE

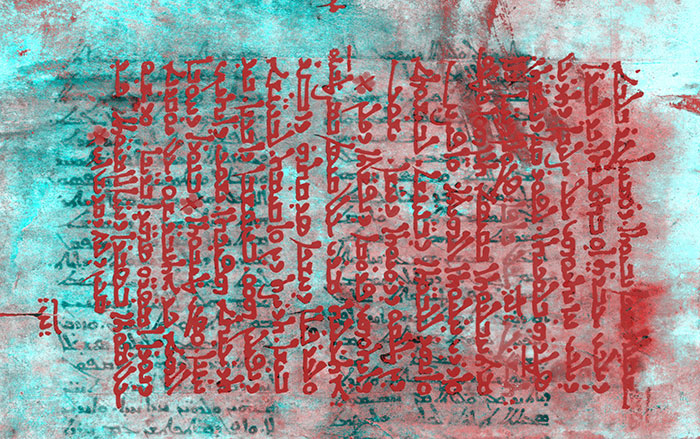

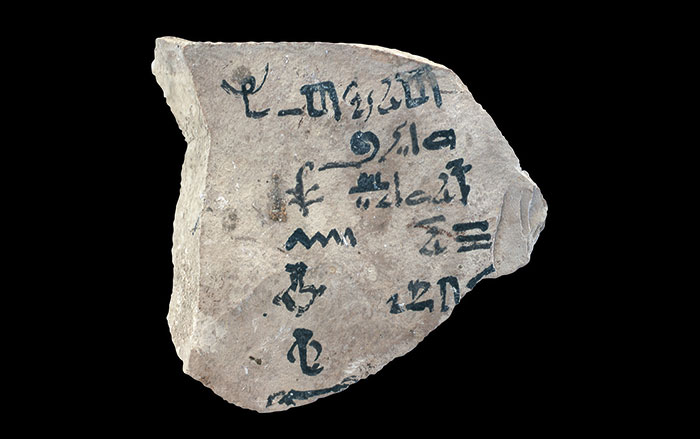

The Côa Valley contains more than 70 discrete sites containing thousands of engravings, protected within what is now a vast archaeological park. The works at Canada do Inferno, a 400-foot canyon, were the first to be discovered. The 36 panels there, which are partially submerged due to another dam, depict ibexes, horses, fish, and aurochs, a type of massive wild ox that is now extinct. At the site of Penascosa, an artist appears to have tried to convey the idea of movement: A stallion in the process of mounting a mare is depicted with three heads that suggest he is bending down. Other sites, including Faia and Vale Carbões, have carvings that were painted or highlighted with ochre.

WHILE YOU'RE THERE

The Côa Valley is in Douro wine country, which produces both table wine and port dessert wine. The Quinta da Ervamoira vineyard is within the boundaries of the archaeological park and houses a museum of the region’s history. Zilhão also recommends a visit to the nearby historical village of Marialva, once a military stronghold that received the charter of the first king of Portugal, Afonso I. Of the picturesque walled village, Portuguese novelist José Saramago writes, “It is this complex of ruined buildings, and the mystery that unites them, the present memory of all those who lived here, that suddenly moves the traveler, brings a lump to his throat and tears to his eyes.”