At first glance, the historic county of Yorkshire in northern England seems as English as can be. It gives its name to Yorkshire pudding, a staple of English cuisine dating back to the eighteenth century. Earlier still, it was home to the royal House of York, whose line included King Richard III. But a closer look reveals a more complicated history. Take Ormesby: Today a suburb of Middlesbrough, its name derives from the Old Norse for “Ormr’s farm.” Or the many streets in the city of York that end in “gate,” from the Old Norse gata, meaning “road” or “way.” Even the city’s name comes from the Old Norse Jorvik.

The source of these Scandinavian-influenced place names and the many more that can be found to this day in northern England dates back more than a thousand years. Starting in the late ninth century, tens of thousands of Vikings arrived in Anglo-Saxon England, first as part of an invading force known as the Viking Great Army, and later as part of a massive wave of settlers. Examining the landscape, history, and archaeology of the region tells us much about what happens when cultures clash but ultimately come to coexist. And it helps explain Anglo-Saxon and Viking interactions.

The Viking Great Army’s arrival in 865 was recounted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: “A great heathen force came into English land, and they took winter-quarters in East Anglia; there they were horsed, and they made peace.” According to the Chronicle, the Vikings spent years campaigning through the territory of the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms—East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex. They proved to be masters at keeping the Anglo-Saxons off balance, making peace with a kingdom one year, only to strike a mortal blow the next. By 880, all the kingdoms had fallen to the Vikings except Wessex, with which they made peace. “The Vikings were very quick and they got quite far inland on their boats,” says Jane Kershaw of the University of Oxford. “They had an element of surprise that the Anglo-Saxons weren’t quite able to anticipate and respond to.”

Viking raiders had been targeting wealthy enclaves on England’s coasts with summertime hit-and-run raids since at least 793, when they launched the infamous, terrifying attack on a monastery on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off the Northumbrian coast of northeast England. Attacks on other monasteries and settlements on England’s east and west coasts followed. Beginning in 850, Viking forces at times spent the winter at coastal sites, allowing them to start their raids earlier in the year. With the arrival of the Viking Great Army, at last, they were able to penetrate deep into England, making their way along rivers and ancient Roman roads, setting up overwintering camps, and wreaking havoc on the Anglo-Saxons. “It seems that the Vikings are after something a little bit different at this stage,” says Kershaw. “They’re still after portable wealth, but they start to have an eye toward acquiring land as well. They start to see England as somewhere they might be able to settle and reestablish themselves as lords with their own families.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the Viking Great Army’s exploits in outsized terms. In a single day’s battle against Wessex, for example, it reports a death toll in the thousands. “The implication is that it’s larger than any previous army seen in England,” says Dawn Hadley of the University of Sheffield. But until recently, there had been little archaeological evidence of its presence. Only one overwintering camp mentioned in the Chronicle had ever been discovered, at Repton, the capital of Mercia, in present-day Derbyshire, where the army spent the winter of 873–874. Excavations conducted there between 1974 and 1993 by Martin Biddle and his late wife, Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle, had revealed a small, heavily defended enclosure covering just an acre or two. Although it was unclear whether the camp extended beyond this fortified area, some experts took these findings to suggest that the Great Army was not actually so great after all, numbering at most in the hundreds—and that the Chronicle’s authors had exaggerated its size to make it appear more fearsome.

Now, however, an archaeological project at another location, Torksey, in Lincolnshire, where the army camped from 872 to 873, has established that it was indeed very large—it was in fact far more than a mere army. According to Hadley, codirector of the Torksey research project along with Julian Richards of the University of York, “We are getting the sense that the force that was at Torksey and that is referred to as an army in the Chronicle actually comprised not just warriors, but people engaged in trade and manufacture, and women and children as well.”

Evidence of the camp at Torksey has been unearthed, for the most part, by avocational metal detectorists. Long active in the United Kingdom, they are strongly encouraged to notify scholars of their finds. When Hadley and Richards learned that a group of detectorists in the Torksey area had discovered ingots, weights, and a concentration of ninth-century coins, including a number of Arabic silver dirhams, all of which appeared to be associated with the Viking Great Army camp, they set out to carefully document the evidence. “We got the detectorists to record their finds more systematically,” says Richards. “We gave them portable global positioning devices to log the coordinates of each discovery so we could plot maps of where everything was coming from.”

The dimensions of the camp that emerged from mapping these finds covered a vast expanse—some 136 acres stretching over six present-day agricultural fields near the east bank of the River Trent north of the modern village of Torksey. “The scale of activity over all those fields suggests a large force, measuring at least in the thousands, with quite a degree of organization,” says Richards. The site is generally dry today as a result of nineteenth-century drainage projects, but the researchers determined that in the ninth century it was a natural island bordered by the River Trent on the west and marshland on the other three sides, which helps explain why the Vikings camped there.

By the time the Viking Great Army overwintered at Torksey, it had been in England for seven years and had already conquered both East Anglia and Northumbria. Archaeologists knew that it could be expected to have accumulated a great deal of treasure, and, in fact, more than 120 Arabic silver dirhams have been unearthed. As is characteristic of the Vikings, the coins had been cut up into pieces to be traded for the value of their metal. These coins are a strong sign of the presence of Vikings, who are known to have traded slaves for them in Eastern Europe. They are only rarely found in typical Anglo-Saxon contexts. “Torksey has the largest concentration of dirhams from any site in Britain or Ireland,” says Hadley. “So that jumps out.” In addition, at least 60 pieces of hacksilver, which was chopped up for use in trade, along with a dozen pieces of rare hackgold, have been found. “If they lost that much material,” asks Richards, “how much silver and gold must there have been in circulation?”

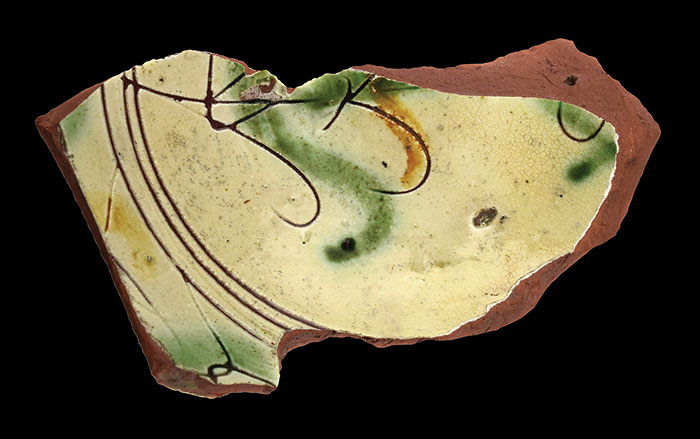

The Vikings at the camp, according to Hadley and Richards, may well have engaged in trade of a sort with local Anglo-Saxons. Scandinavians at the time generally used raw metal for trade rather than coins. Several hundred weights of the kind they are known to have used to facilitate exchange have been found. However, although the Vikings had negotiated a peace with the Mercians before setting up camp, it is unclear, according to Kershaw, how cordial relations would have been with those living nearby. “I don’t see what Viking camps would have had to offer locals,” she says. “I see them as being quite parasitic on the local landscape. They would have had to acquire a lot of provisions to sustain a large army, but I don’t think they would have done that peacefully. There might have been forced, coercive trade, but I don’t think these are places where you would walk up and buy a couple of pots. The trade that was going on was probably more among the army members themselves.”

The camp at Torksey would have been self-sustaining in some respects. “It’s almost like a town on the move,” says Hadley. Life within its confines is becoming clearer for researchers. Members of the army appear to have had leisure time on their hands, as shown by the number of lead gaming pieces that have been found at the site. The presence of metalworkers is indicated by collections of scrap copper and iron, apparently gathered to be melted down. Women seem to have been part of the camp as well, as suggested by the discovery of spindle whorls and other tools used to work textiles. It is unclear, though, whether these were Scandinavian women who had come along with the army as part of families, or captives taken as spoils of war. Added to all this are hints of an aspiring kingdom attempting to establish itself. Three iron plowshares discovered together may have been headed for the scrap heap. But, according to Richards, “The more interesting possibility is that they were already thinking about seizing agricultural estates and acquired the plowshares with that aim in mind.”

The peace the Vikings had made with the Mercians in Torksey was soon broken. The next year, 873, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Vikings charged into the kingdom’s capital, Repton, some 60 miles southwest along the Trent. There, they sacked a monastery, sent the king, Burghred, fleeing to Paris, and replaced him with a figurehead named Ceolwulf. This sort of bait and switch was typical of how the Vikings managed to get the better of the Anglo-Saxons. “The Anglo-Saxons did their standard thing of making an oath, exchanging hostages, and paying the Vikings some money, and then they expected the Vikings to go away,” says Kershaw. “But the Vikings don’t play by the same rules. They take the money, but they come back the next year. They swear an oath, but they don’t keep it. The Anglo-Saxons don’t quite know how to negotiate with someone who doesn’t respect their laws of peacemaking.”

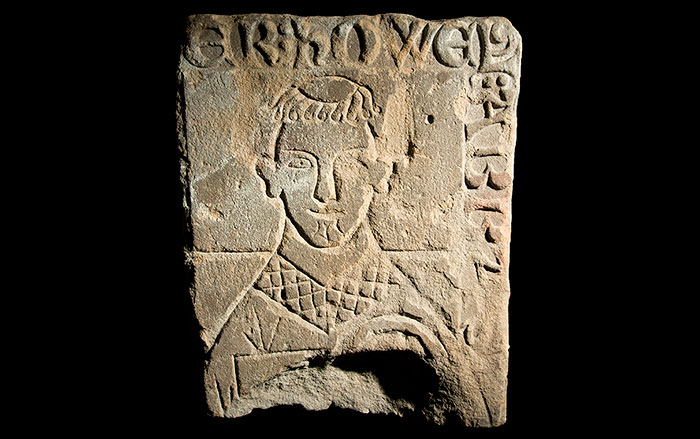

The early Biddle excavations at the Repton overwintering camp of 873–874 were able to illustrate how the Vikings behaved in victory. After defeating the Mercians, the Vikings ran roughshod over some of their most sacred territory. They built a heavily fortified D-shaped enclosure with St. Wystan’s church to the south serving as a gatehouse and possibly an eating hall. A large defensive ditch was constructed, cutting through Mercian cemeteries to the east and west before turning north to meet the River Trent. Archaeologists also discovered what are believed to have been at least 10 carved Anglo-Saxon stone crosses smashed into small pieces. Says Biddle, who is now an emeritus professor at the University of Oxford, “They broke the place up.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers no insights into the nature of the battle for Repton, but evidence shows it was likely a bloody one. Next to a crypt where members of the Mercian royal family were buried, the excavation unearthed a Viking warrior who had suffered grievous injuries and had been laid to rest alongside an iron sword, with a silver Thor’s hammer around his neck. “He died a very violent death indeed,” says Biddle, reflecting back on the discovery. “He looks as though someone stabbed him more or less in the eyes. But the real great wound, which we found immediately upon excavation, was a huge cut into the inner side of his left femur. It could only have been made by someone standing above him, perhaps with a heavy sword or an ax.” A boar’s tusk had been placed between the warrior’s thighs, possibly to replace genitalia damaged or severed in his final battle.

Many more Vikings appear to have been buried in a charnel mound outside the fortified enclosure, in what was once an Anglo-Saxon mausoleum. There, Biddle discovered the disarticulated remains of at least 264 people. The remains belonged overwhelmingly to adult males. Found among them were an iron ax, two fighting knives, and five silver pennies dating to 872–874. As part of a new archaeological examination of the site, radiocarbon dating and analysis of the bones have demonstrated that they date to the time when the army overwintered at Repton and that they had been subjected to extensive violence and trauma. Cat Jarman of the University of Bristol, codirector of the current project at Repton, suggests that many of those whose bones were found in the deposit were Viking warriors killed in battle elsewhere and then buried during the winter. “We don’t actually know what happened to the thousands of people who died in battles that we read about in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” she says. “But there are a lot of examples from across the Viking world of people moving bones, so it wouldn’t be surprising if the Viking Great Army took bones from battle sites and put them in this context.”

It also appears that the overwintering camp at Repton extended beyond the heavily fortified enclosure. Excavations near the charnel mound have turned up Viking weapons—an arrowhead, a fragment of an ax—as well as lead gaming pieces and evidence of metalworking. Several clinker nails typically used in ship construction have also been found. “We know that they moved up and down the rivers, and their ships would have needed frequent repairs,” says Jarman. “They were probably getting ready for the next season’s attack.”

After overwintering at Repton from 873 to 874, the Viking Great Army split in two. One part, under the leadership of Guthrum, headed south and was ultimately defeated in 878 by Wessex and its king, Alfred the Great. To make peace, Guthrum was baptized along with 30 of his warriors, and ended up reigning as an Anglo-Saxon-style king over a swath of territory allocated to him by Alfred. The other part of the army headed north and went on to “share out the land,” as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle puts it, in Northumbria in 876, Mercia in 877, and East Anglia in 880. This seems to suggest that the Vikings took over vast stretches of England, but how did it work exactly? “We don’t really know,” says Kershaw. “The consensus is that they do take over the Anglo-Saxon estates, but I think you probably have Anglo-Saxon communities left in place alongside the new Scandinavian ones.”

The area of northern and eastern England inhabited by the Vikings ultimately came to be known as the Danelaw, after the Anglo-Saxons’ belief that most of the invaders had come from Denmark. New evidence suggests that once the army members settled there, large numbers of Viking women came over to join them. Kershaw has analyzed metal-detected finds from rural parts of the Danelaw and identified 125 women’s brooches of types that have turned up nowhere else in England, but have been found in Scandinavia, particularly in Denmark, and date to the Viking Age. “It’s clear that these items are coming in on the clothing of women arriving from southern Scandinavia to settle in rural England,” she says. “So I think there is a second wave of migration following the settlement of the Danelaw that includes women and children.” The discovery of brooches that mix Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian elements indicates that the two communities intermingled to a great degree. “These styles are seen as somehow fashionable by the locals,” says Kershaw. “There is a desire to emulate these styles, which suggests that Scandinavians are either in political control or they’re seen as exotic.”

The Anglo-Saxons, united under the House of Wessex, regained rule of the Danelaw by the mid-tenth century, but the Scandinavian influence endured. In a 1086 survey of England called the Domesday Book, nearly half the place names in Yorkshire are Scandinavian. “It’s not just towns and villages that have these names,” says Kershaw. “It’s really small features of the rural landscape, such as rivers, hedgerows, and little parks.” More than a thousand years after the Vikings first arrived, and despite their eventual defeat, their influence remains etched into the fabric of England to this day.