A red sandstone block props open the door to Gyula Kereszturi’s wine cellar in a small village in southern Hungary. Kereszturi, who ekes out a living selling homemade wine and plum brandy in one of this country’s poorest regions, found the block more than two decades ago when he expanded the cellar. Over the years, it has made a good doorstop, or sometimes a makeshift table.

But it used to be much more than that. This block was once part of the revered mausoleum complex of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire’s most prolific builder and accomplished military leader. Although Kereszturi and other locals had long referred to the occasional red bricks they found buried in their yards as “Turkish ruins,” they had no idea that anything significant had ever stood there. And, until recently, neither did archaeologists. That all changed when remote sensing and later excavation revealed that the ground under Kereszturi’s house and vineyard might contain the ruins of Turbek, a once-flourishing Muslim pilgrimage destination on the ground where Suleiman died of natural causes in 1566 during the brutal Battle of Szigetvar, a crucial contest in the fight to expand the Ottoman hold on Europe.

“This is the most exciting find from the Ottoman period in Hungary,” says Norbert Pap, a geographer at the University of Pecs, who leads the ongoing work of the interdisciplinary team that first identified the ruins, whose location had eluded generations of scholars. The discovery of Turbek is significant because it is the only town the Ottomans founded in Hungary during the nearly 150 years they ruled there. “It is a symbol of the Ottoman occupation of Europe, and an expression of dar-al-Islam,” explains Pap, using the Arabic term that refers to a region under Muslim rule and where Islamic law prevails. The newly unearthed site, which covers about 10 acres and contains the foundations of a mausoleum, a mosque, a Sufi monastery, and what is likely a military barracks, offers a window into the long-vanished and oft-overlooked cultural, political, and economic life that the Ottomans carved out for themselves more than 600 miles from their capital of Istanbul.

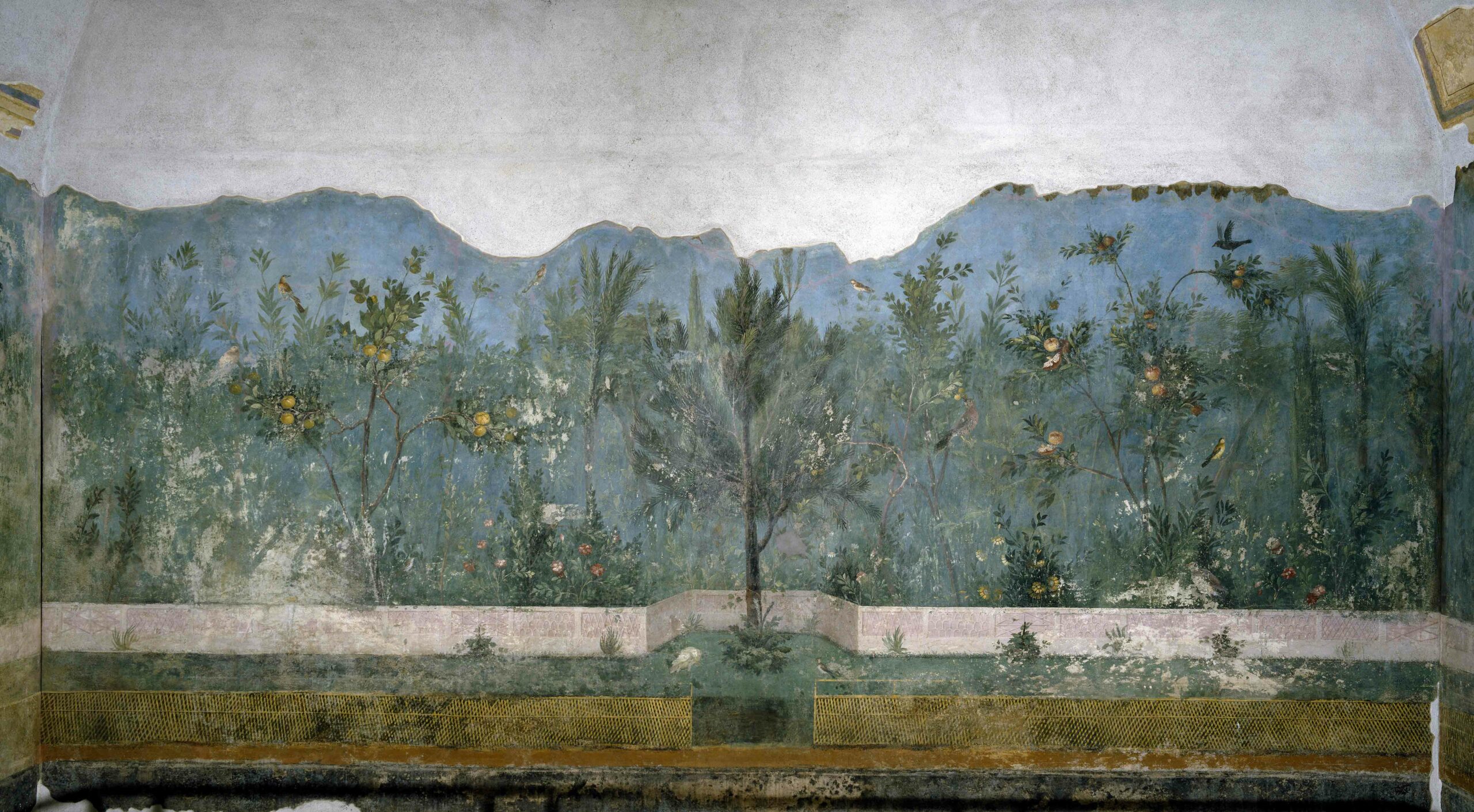

Founded in the Anatolia region of what is now Turkey in 1299, the Ottoman Empire eventually became a global power and remained such until its demise during World War I. The empire reached its height in the sixteenth century under its longest-serving ruler, Sultan Suleiman I, known as Suleiman the Magnificent. During this period, the Ottomans extended their rule to almost all of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Europe. This solidified their control over lucrative trade routes, and the new wealth they amassed was reflected in a grand building spree in the capital of Istanbul. But Suleiman was intent on conquering more of Europe, especially the capital of the Habsburg Empire, Vienna. This put Hungary in the Ottomans’ strategic path. Beginning with their victory at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, the Ottomans began to gradually conquer pieces of Hungary, turning churches into mosques, taking over fortresses, and adding elements such as bathhouses to existing cities. Although the Ottomans gained significant ground, the continuing fight put up by the Hungarians challenged their fragile hold on power.

According to historians, the Ottomans were confined to living a rather isolated existence in the areas they conquered. “They adopted almost nothing from Hungarian culture and instead built a high culture of their own on Hungarian soil,” explains Pal Fodor, director of the Institute of History at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest. The local Hungarian population also never adopted Islamic culture or religion on any large scale. “All social factors in Hungary, from the king at the top to the peasants at the bottom, regarded the conquerors as savages, pagans, and natural enemies, as persecutors of the country and of the Christian faith, and, later, as archenemies,” Fodor says. “The anti-Ottoman struggle was conceived partly as self-defense, and partly as a war that protected the entire Christian world. This explains why, despite long cohabitation and occasional political cooperation, Hungarian and Ottoman Turkish cultures influenced each other only superficially.” To protect itself from further Ottoman encroachment, Hungary relied on a series of fortresses. One of these, Szigetvar, dating to the Middle Ages, became especially important, as it stood just west of the Ottoman-occupied Hungarian city of Pecs, and protected the western half of Hungary, parts of Croatia, and the roads leading to Vienna. Perched on a hilltop surrounded by a stream and marshy land, Szigetvar, which means “island castle,” was able to ward off several Ottoman attacks in the 1550s.

Growing old and more determined to conquer Vienna, Suleiman set out with his troops in the spring of 1566 for a three-month-long march to Szigetvar in another attempt to eventually get to Vienna, where in 1529 his troops had been dramatically defeated. When they arrived in the area, the Turks set up tents on a small hill just north of the fortress. On August 9, they began bombarding it. Just over four weeks later, on September 7, the besieged Hungarian forces, who had run out of gunpowder, food, and water, made a futile attempt to attack the Ottomans. Many Hungarian soldiers were killed and the castle fell into Ottoman hands, but the Turks had suffered such heavy losses as well that it would be another 130 years before their next attempt to take Vienna. This was recorded as a heroic moment in Hungarian history. For years, the fight with the Ottomans was seen not just in nationalistic terms, but also as a spiritual battle between Christianity and Islam. Miklos Zrinyi, the great-grandson of the commander of the Hungarian troops at Szigetvar, writes in his 1646 epic poem, The Peril of Szigetvar:

We, moreover, must fight not for any trivial reason

But for our beloved Christian homeland

For our Lord, for our wives, for our children

For our honor and our lives.

This battle in the hinterlands of central Europe also left a deep and lasting mark on Turkish history. The night before his troops conquered the castle, Suleiman, who had ruled the empire for 46 years, died in his tent from old age, just shy of his 72nd birthday. His body was eventually taken back to Istanbul, where he was interred. But stories later emerged that his heart and other internal organs had been left in Hungary, buried in the ground where his tent had once stood. According to this widespread legend, Suleiman’s inner circle kept his death a secret so his troops’ morale wouldn’t be damaged. His advisers are said to have departed from Islamic tradition by removing and burying his organs and embalming his body to prevent its decay in the late summer heat before it could be transported back to Turkey. Most scholars, however, dismiss the story as folklore.

Regardless of how Suleiman’s body was handled, the place where he died emerged as meaningful. His successor, his son Selim II, soon ordered that a tomb be built to honor Suleiman. “The construction of this tomb had great symbolism,” says Ali Uzay Peker, professor of architecture at Middle East Technical University in Istanbul, who has also worked at Turbek. “It was at the border between the Ottoman and Habsburg realms in eastern Europe. Hence it aroused spiritual attachment to the land.”

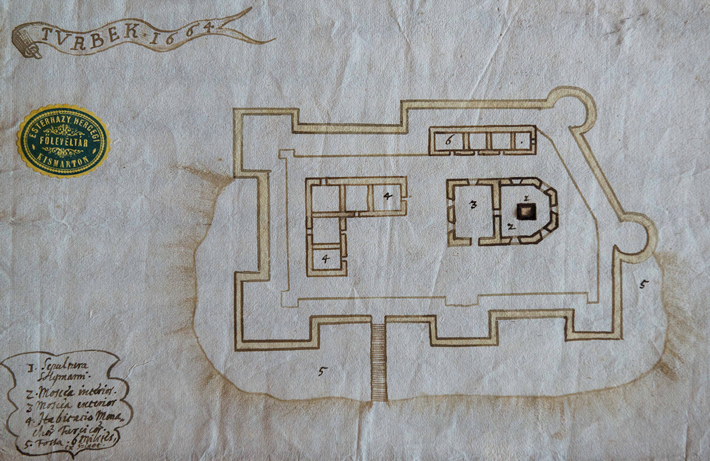

A mosque, an Islamic dervish monastery, and a military barracks were built around the tomb, according to a 1664 sketch by Pal Esterhazy, a Hungarian military commander. A caravansary where traders and travelers could leave their horses, shops, a bathhouse, and other buildings were then established around the inner core of the complex to accommodate a growing number of Muslim pilgrims. These pilgrims came mainly from Turkey and elsewhere in the Balkans, according to the descriptions of Evliya Celebi, the famous Turkish traveler who journeyed for 40 years around the lands of the Ottoman Empire, recording his observations in the epic Seyahatname, or “Book of Travels.”

Historical accounts also indicate that ascetic practices of Sufism developed at Turbek, and that it became an important center of Islamic mysticism in the region. Several influential mystical books were written there, and among the pilgrims were members of other Sufi orders. Contemporary documents attest that about 60 Ottoman soldiers, who lived in a barracks adjacent to the mosque, tomb, and monastery, faithfully guarded the area. Although other mosques and dervish monasteries were built in Hungary, Turbek was unique because it was set up as its own settlement, outside Szigetvar. This breaks with the overall pattern of Ottoman residents simply moving into fortified areas they had conquered, as happened in the cities of Pecs and Buda, on the Danube River. Fodor says, “The shrine and the town around it completely differed from the usual Ottoman centers that emerged in Hungary at that time.”

By the late seventeenth century, the Ottomans were slowly losing their grip on power in Hungary as the Habsburgs began to win more battles, eventually pushing the Turks out of the country. Ottoman life at Turbek came to an end in 1693, when it was taken over by Habsburg forces and almost completely destroyed. Turbek was reduced to a memory, and ultimately a legend—although through the centuries there have been stories of locals digging in search of Suleiman’s organs, which they had heard were buried in a golden bowl.

Archaeologists had long wondered where Turbek actually stood, and if there was anything left of it. There have been abundant, yet conflicting, theories about its location. Since 1913, a plaque outside St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church near Szigetvar has declared, in both Hungarian and Turkish, that the building was established on the land where Suleiman’s heart was buried. Another local legend claims that his organs were interred on the banks of the Almas Stream. There, in 1994, a symbolic tomb of Suleiman was created as part of the Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Park, which was established to mark the sultan’s 500th birthday. But archaeological excavations had never revealed any conclusive evidence of Ottoman settlement—much less a mausoleum complex—in these places. “There were lots of arguments but no one could find evidence,” Pap says.

In 2012, he and his team decided to take a different approach to the question. Rather than rely on local tales about where Turbek used to stand, they gathered data from old maps, crop records, and other sources, and used geographic information systems technology to reconstruct the landscape and topography of the area around Szigetvar in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “How much had changed since then was shocking,” Pap says. “And it quickly became clear that Turbek could not have been at the church or the Friendship Park because those areas were way too marshy back then.” Rather, the landscape model indicated that the long-lost settlement likely sat in the middle of what today is a vineyard, about 2.7 miles northeast of the castle.

According to Pap’s reconstruction, this area would have been on a small hilltop, a detail recorded by Suleiman’s aides in their descriptions of where tents were placed during the battle. That area also offered a view of the castle, another detail reported by Suleiman’s aides—and something not available at the proposed church and Friendship Park locations. When Pap visited and talked to the owners of the vineyard there, they offered him a glass of “Szemlohegy” wine. “I was shocked,” Pap recalls. This is the same name that Suleiman’s aides had recorded for the hill where they set up the tents for the Battle of Szigetvar. “The name of this place had survived in the name of the wine.” In 2015, geophysical examinations revealed the foundations of five structures spread out over 10 acres just over a foot below the surface of the vineyard. Furthermore, the layout of the buildings was consistent with the 1664 sketch of Turbek that Esterhazy had made.

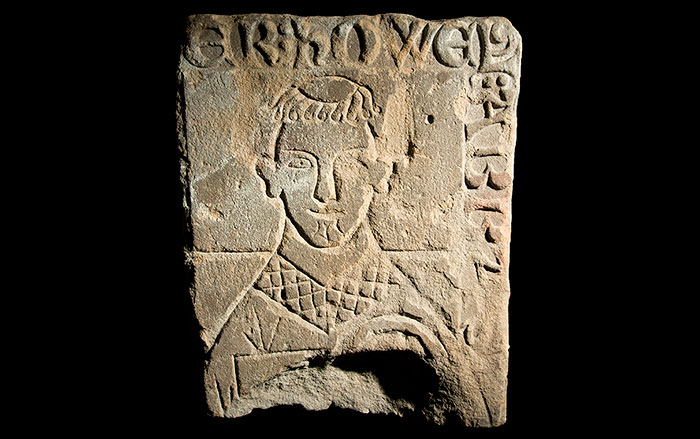

The team began excavating in 2016, first uncovering the foundations of a large square building. “We had more and more evidence that this building must be a tomb, because it had no mihrab and no minaret,” says Erika Hancz, an archaeologist at the University of Pecs who oversaw the dig. The team found several small artifacts within the foundation of this square building, including carved stone palmettes, popular as a decoration and seen on many Ottoman structures, including Suleiman the Magnificent’s burial chamber and mosque in Istanbul. “The building materials and techniques and the objects of daily use confirmed that the site belongs to the Ottoman period in Szigetvar,” Peker says. The fact that the layout matches Esterhazy’s drawing, along with the absence of other known Ottoman settlements in the area proves, at long last, that this is, indeed, the mausoleum of Suleiman.

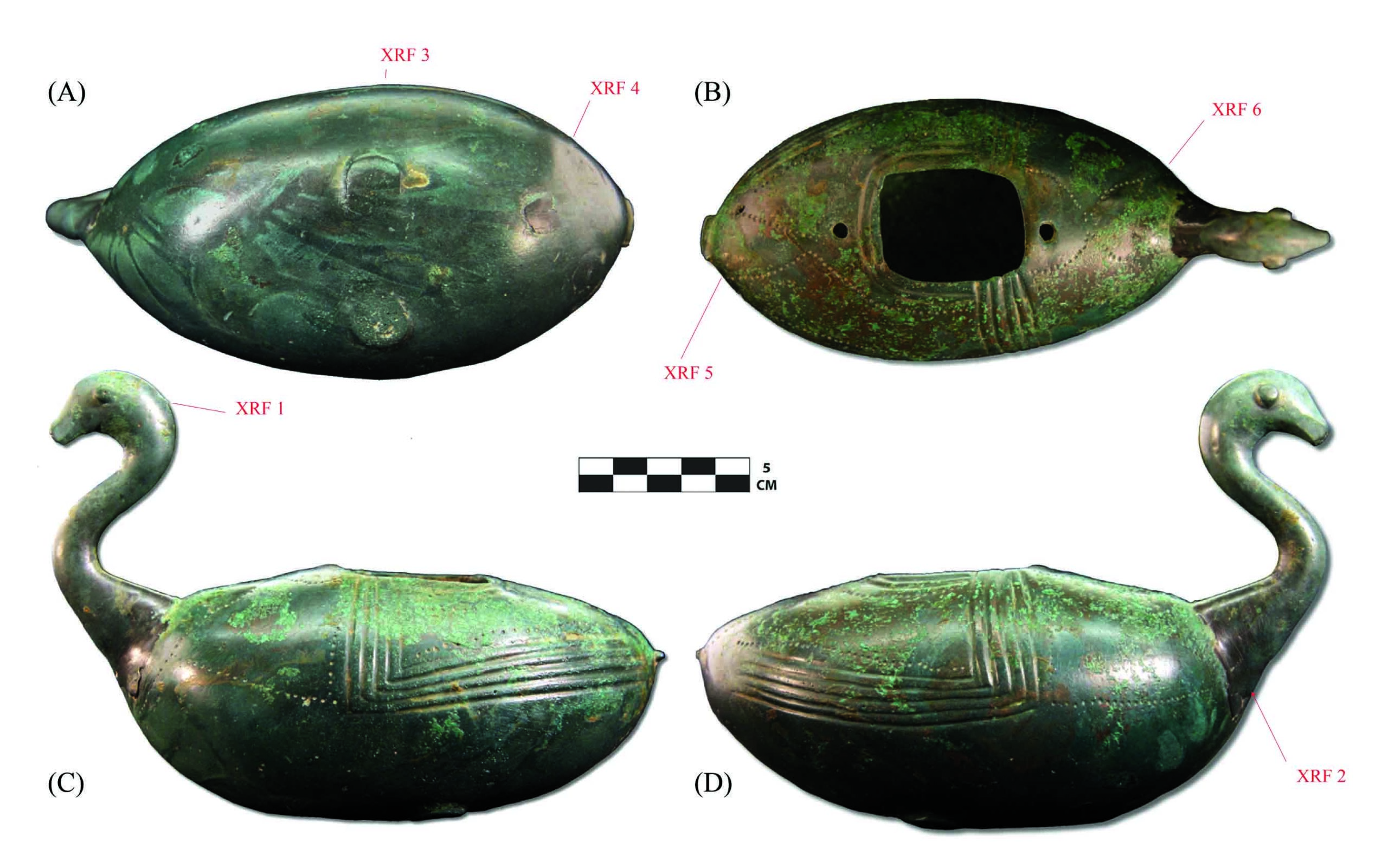

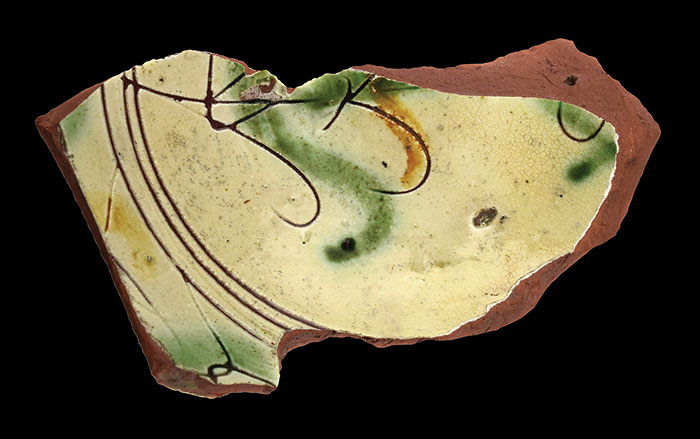

Another building—identified as the dervish monastery—contains many small chambers, and excavation there uncovered Ottoman coins along with many everyday objects, including parts of a cooking stove, pieces of ceramic and glass vessels, and metal artifacts such as belt buckles. The style of these household items is similar to those found in the Balkan countries south of Hungary, Peker says. These objects, along with historical evidence, indicate that the inhabitants of Turbek were mainly Muslims who moved here from the Balkans. But, explains Hancz, the pieces of brightly colored ceramics typical of the southern Anatolian region of Turkey and a fragment of porcelain from China speak to the site’s global connections. Horsemen’s shoes and spurs, along with a millstone and remains of grains offer evidence that the residents of Turbek grew crops.

The fact that all that is left of Turbek are building foundations no more than 15 inches tall is consistent with eyewitness accounts of Habsburg soldiers when they drove the Ottomans from Turkey. “The Habsburgs did their best to destroy the site to the bones,” Peker says. This degree of destruction reveals how important the place had become in Ottoman culture and politics—and how much the Habsburgs wanted to erase that. “It’s clear that they aimed to wipe out all traces of the Ottomans,” Peker says. “This can give us a sense of the significance attached to the tomb when it stood here: It was a visible sign of the Ottoman presence on the border and it was a reminder of land claims.”

The team’s next step is to excavate the foundations of the building they believe is the military barracks, and to then look further afield for the baths, caravansary, and other surrounding structures mentioned by the traveler Celebi. “We don’t know everything, clearly, but we have enough evidence to imagine the site, and hope to find the other buildings,” Hancz says. “We still have a lot to do.”