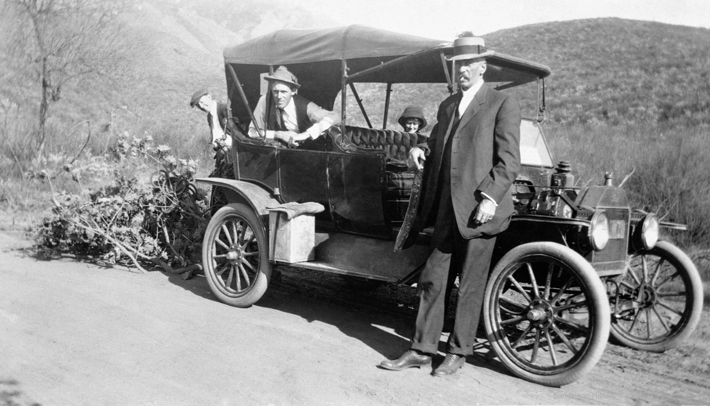

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Palomar Mountain became a popular destination for tourists from San Diego. Though the mountain lies just 60 miles northeast of the city, at the time, the arduous trip to its summit took several days via horse, horse-drawn carriage, or automobile. The final six miles to its 6,140-foot peak, up a winding grade from the mountain’s base, known as Tin Can Flat, took a full day. The single-lane, unpaved track ran alongside sheer drop-offs and was so steep that drivers would often tie trees to their bumpers for the descent in an attempt to spare their brakes. On the dry, dusty way up, it wasn’t long before the horses were panting for water and the Model T radiators were bone dry. So it was with great relief that, two-thirds of the way up the slope, travelers would come upon a spring attended by an aged African American man named Nathan Harrison.

Harrison greeted the travelers with a wide grin and a plentiful supply of water to slake the thirst of man, woman, horse, and car. Then, speaking in a thick accent that nodded to his origins in Southern slavery, he would regale visitors with tales of his life on the mountain. This was a world of grizzly bears that could chew wooden traps to pieces. “When I first came to the mountain, bear were thick,” Harrison once recalled to Robert Asher, one of his neighbors on Palomar. “You could just hear them poppin’ their teeth.” There were mountain lions that leapt upwards of 35 feet—including one Harrison claimed to have taken down that measured “fourteen feet seven inches from tip to tip.” In addition to harrowing run-ins with these wild predators, Harrison told of his confrontations with rustlers who aimed to poach his ample stock of horses, cattle, and sheep.

Many of Harrison’s stories had the air of embellishment—he even told a few children he’d come to California in 1849 by boat, braving the treacherous waters around Cape Horn. Despite the improbability of his tales, or perhaps because of it, Harrison’s audience of white San Diegans exploring the wilderness just outside their city lapped it up. When they returned home, they told others of their encounters with Harrison, and before long, he was one of the highlights of a trip up Palomar Mountain. (See “The Birth of Western Tourism.”) “Visiting Harrison was like stepping into a time machine and going back to the Old South,” says Seth Mallios, an archaeologist at San Diego State University. “People were magically transported back fifty years and three thousand miles away.”

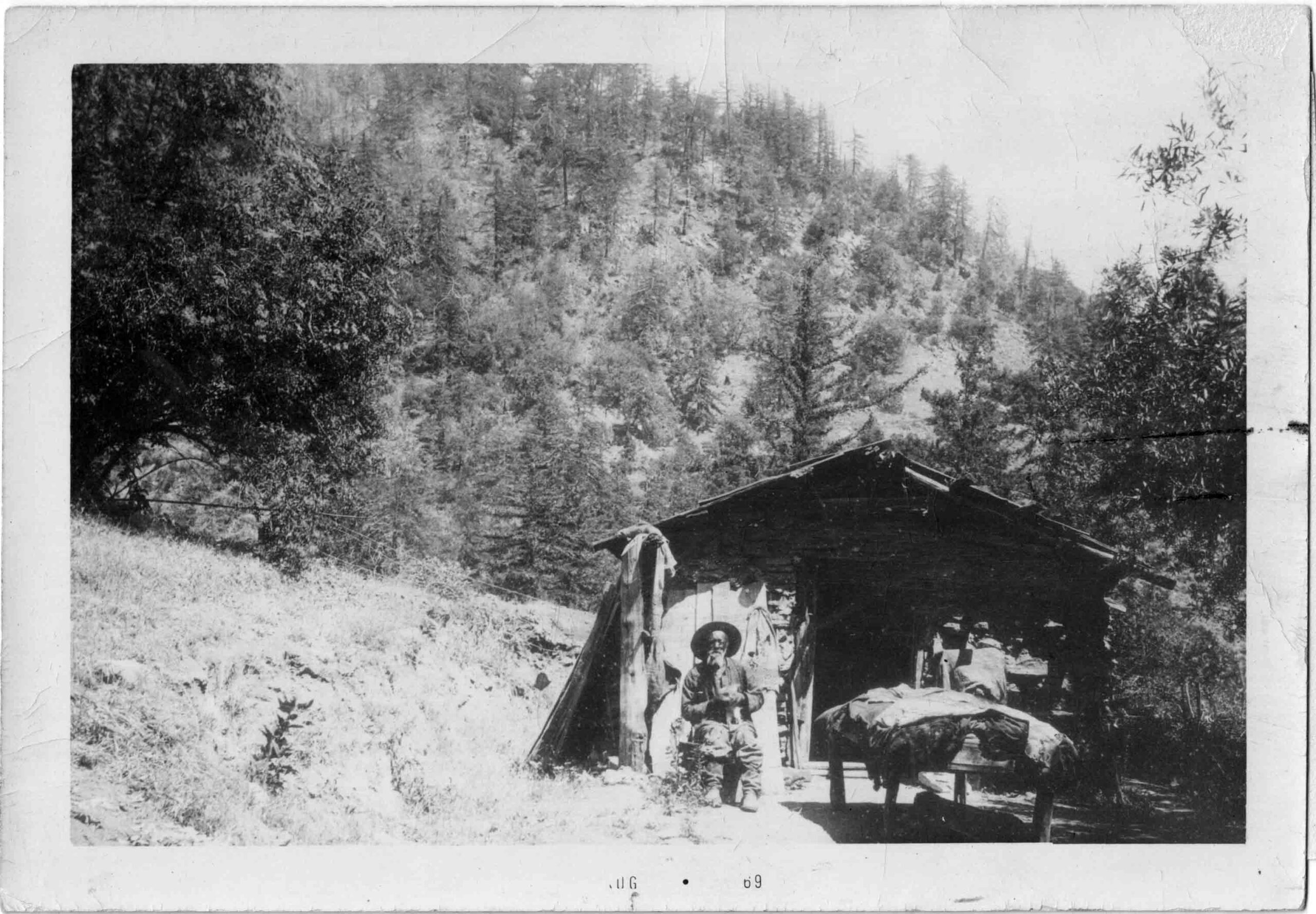

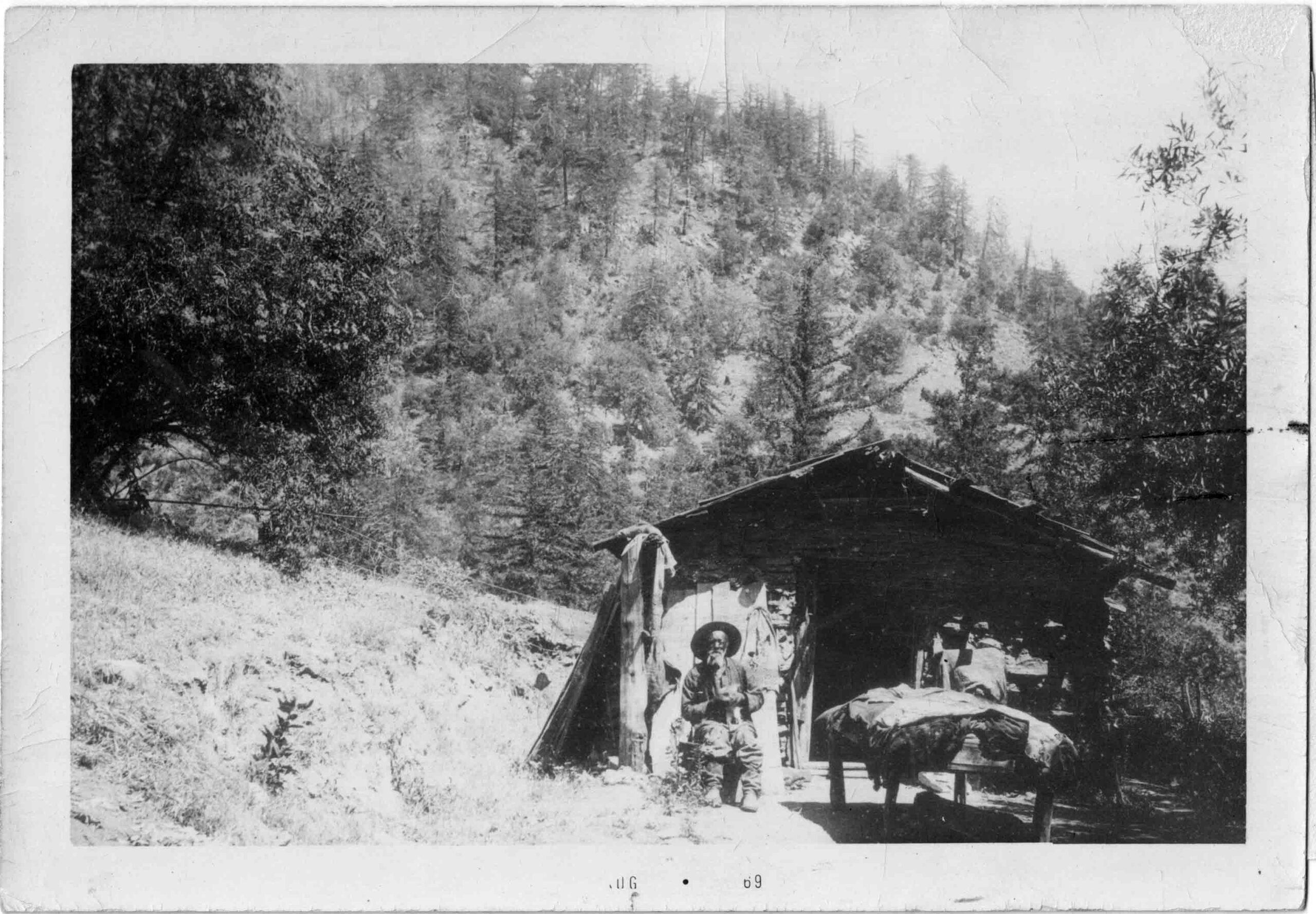

Harrison would often invite travelers to his cabin for further entertainment. Allan Kelly, who trekked up the mountain with his family in 1908 when he was seven years old, later recalled, “He had a lovely spot: a far distant view to the ocean…about an acre of good soil for a garden and a few apple and pear trees.” In exchange for Harrison’s hospitality, the visiting city folk came bearing gifts—typically tins of meat, bottles of alcohol, and clothing. Many also brought along early Kodak Brownie cameras to capture snapshots of their host. Although he lived in a relatively remote location, Harrison was likely the most frequently photographed person of his time in the San Diego area, suggests Mallios, who has extensively researched Harrison’s life and leads excavations of the site where his cabin once stood. “There was nothing convenient about taking his photograph,” says Mallios. “People were aware that he was someone they wanted to take a photo of, whether it was to show that they had made it to the top of this very perilous mountain, or to capture something that you just didn’t see anywhere else.”

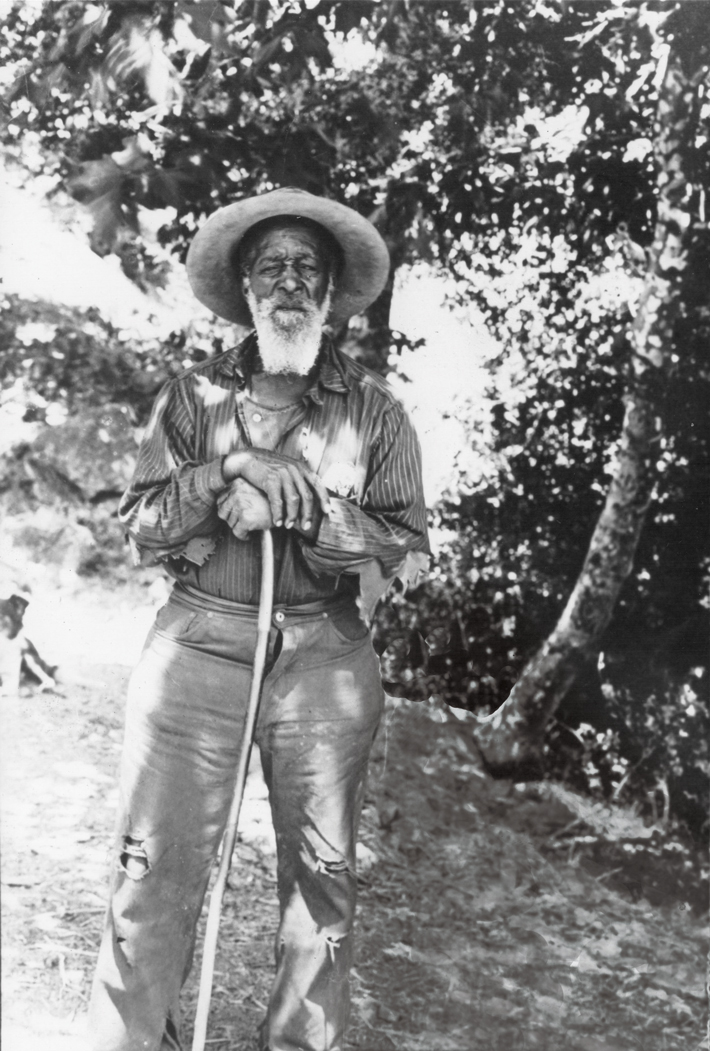

In these photographs, and when entertaining visitors, Harrison came across as exceedingly humble. A scraggly white beard hung from his chin, and he wore tattered clothes—his friend Robert Asher reported that he once deliberately changed into his most ragged pair of overalls before being photographed. Whereas a typical rancher of his time would carry a rifle and warily approach visitors on horseback, Harrison greeted tourists unarmed and on foot, aided by a walking stick. “He was very charismatic, smiling,” says Mallios. “He made fun of himself and couldn’t have been less threatening.” However, as he continued to learn about Harrison, Mallios found that there was far more to the mountain man—and the ways in which he managed to prosper—than first met the eye.

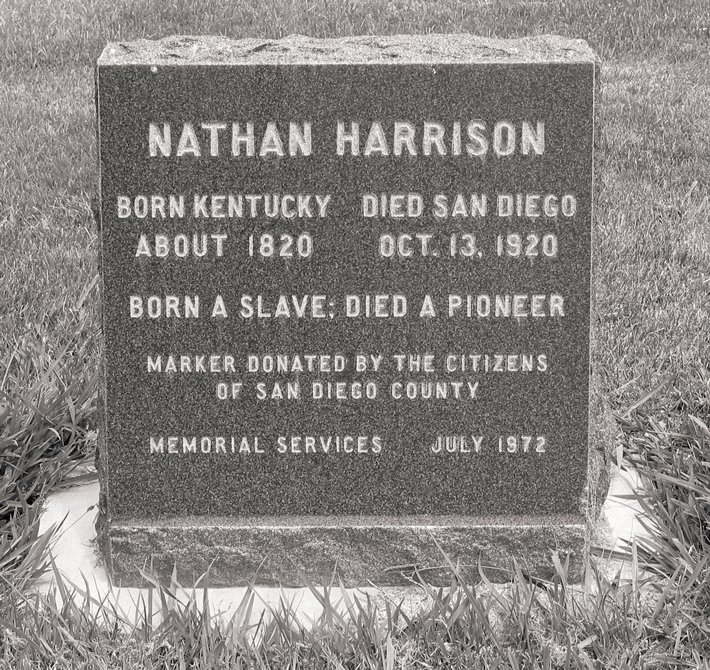

Many accounts of Harrison’s life and adventures have been written, beginning when he was still alive and continuing long after he died in 1920. They tend to agree that he was born into slavery and eventually made his way to the San Diego area, becoming the region’s first African American homesteader. Between these two events, various tellers have claimed, apocryphally, that he daringly escaped slavery by floating down the Mississippi River on a raft in the 1840s, à la Huckleberry Finn and Jim; that he helped win California from Mexico by fighting in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt; and that he drove the first wagon train over Tejon Pass in 1854, opening the route that connected California’s Central Valley with Southern California.

Mallios has determined that Harrison was most likely born in Kentucky in the 1830s, and that during the Gold Rush his owner brought him to Northern California, where he toiled as a miner in the 1850s and 1860s. He appears to have gained his freedom when his owner died, and then migrated south, where he worked at a variety of occupations and, in 1879, homesteaded land in Rincon, near the base of Palomar Mountain. Harrison was briefly married twice, both times to Luiseño Indian women who were part of a community that lived on the mountain. By the late 1880s, he had settled on the slopes of Palomar as one of its first non-Native residents. According to the 1880 census, Harrison was one of just 55 African Americans in all of San Diego County. In 1892, he successfully filed a water claim for the spring associated with his property. This meant it was within his rights to charge for the spring’s use. But Harrison always provided water gratis to the visitors who arrived in increasing numbers after 1900, when the roadway was widened somewhat and a regular car service was established to shuttle tourists to a mountaintop hotel.

Exactly what drew Harrison to make his home some 4,000 feet up Palomar Mountain is unknown. It may have been his connections to the Luiseño, who gave him the land where he built his cabin. Harrison’s desire to tend sheep, which thrive at higher elevations, may also have been a factor. But Mallios suggests that the security afforded by such an isolated spot was likely a strong enticement as well. Many of Southern California’s white settlers came from the South and brought fiercely racist, segregationist attitudes with them. Los Angeles, which Harrison visited occasionally, was commonly known as “The Hell-Hole of the West.” According to Louis Salmons, another neighbor on the mountain, “He never slept in Los Angeles overnight. He’d saddle his horse and go out on the hills. He said they was killing people every night.” Dangerous for all, the city was particularly hazardous for African Americans. Likewise, Escondido, one of the closest settlements to Palomar Mountain, was a “sundown town,” where white men patrolled the streets at night and attacked any African Americans they came across. “For Harrison, I think living on the mountain was in part a safety issue,” says Mallios. “When you venture up to the site, you just feel removed from everything. You are high above the valley, you can see people coming from miles and miles away, and no one is going to sneak up on you.” Indeed, Harrison was known to spend hours sitting on a boulder at an overlook called Billy Goat Point—likely named after him, for the hair on his chin—from which he could keep watch on anyone making their way up the mountain.

EXPAND

The Birth of Western Tourism

The rise of tourism on Palomar Mountain took place at a time when Americans were discovering the allure of wilderness outings, particularly in the West. “There’s this irony that as soon as the California government was able to annihilate the Indigenous population and steal most of their land—right at that moment—there was this romance of the vanishing Indian and this attempt to try to reclaim an experience of rugged naturalism,” says San Diego State University archaeologist Seth Mallios. With the introduction of the Ford Model T in 1908, Palomar became a magnet for early car enthusiasts. “This is all part of the new frontier for where the automobile can take you,” says Mallios. “Many people had never been on a ride like this before, and many of the automobiles didn’t make it up. Others had to back up the mountain, and others burned out their brakes and went out of control down the mountain. Some of my favorite photos are of these old cars with trees tied to their bumpers to help them slow down on the way back down.”

Even before the wide availability of cars, tourists scaled the mountain in horse-drawn carriages, attracted at least in part by the hospitality of Nathan Harrison, a formerly enslaved man who lived two-thirds of the way up the slope and was legendary for his folksy tall tales of life in the backcountry. To Ryan Anderson, an anthropologist at Santa Clara University, there is something sinister to the dynamic between Harrison and his white audience. Anderson notes that a number of tourist attractions of the time involved “exotic” individuals put on display. These include Ota Benga, a Mbuti man who was kidnapped from the Belgian Congo in 1904 and later exhibited in New York City’s Bronx Zoo, and Ishi, a Yahi man showcased at a museum in San Francisco starting in 1911, where he was advertised as “the last wild Indian in California.” “These displays are rooted in a lot of racism, imperialism, condescension, and sort of gawking exotification,” says Anderson. “Harrison fits right in there, but at the same time his case is kind of unique.” While Ota Benga and Ishi had little to no choice in being exhibited, Harrison opted to engage with tourists and cultivated a persona that would appeal to them.

In excavations of the site of Harrison’s cabin launched in 2004, a team led by Mallios has uncovered plentiful evidence of his interactions with tourists. “In multiple records from the 1900s, they talk about the standard kit that you bring to Harrison: a pair of pants, a tin of food, and a bottle of alcohol,” he says. The excavations, in fact, have turned up more than 200 mismatched clothing buttons, a large number of meat tins, and liquor bottles from all over the world. The sheer number of buttons is particularly impressive. “If this were some other site,” Mallios says, “we might have concluded that there were a dozen people living here with how many buttons were there.”

The archaeologists also unearthed a small piece of convex glass with a ridged nickel edge that puzzled them at first, until they realized it was the lens from a Kodak Brownie camera. And, buried under the patio of Harrison’s cabin were a number of extremely deteriorated automobile inner tubes dating to the 1910s. He had apparently stowed supplies that might prove useful for those attempting the challenging drive up the mountain. In a sense, Mallios points out, Harrison was analogous to the proprietor of a modern-day service station, ready to provide water to keep one’s conveyance running—be it horse or car—and supplies such as spare inner tubes in case of equipment failure. The items at the site relating to tourism all date to after 1890, whereas earlier material, such as tools, horseshoes, horseshoe nails, and buckles, reflects Harrison’s work as a rancher. This matches accounts suggesting that, as he grew older and less physically able, Harrison shifted his energies from tending his flock to entertaining his visitors.

A range of other artifacts, however, presents an image of Harrison very different from the one known to the public. Most numerous among these are more than 200 fired rifle cartridges discovered in the vicinity of his cabin. This evidence suggests that Harrison not only owned rifles, but also that he was far from shy about firing them in his own backyard. He was never armed when he went to greet visitors, though, and a rifle appears in only one of the 31 known photographs of him. Even in that image, the firearm is off to Harrison’s side, barely visible against a wooden platform. By contrast, white men who settled on the mountain in the years after Harrison arrived invariably had a rifle in hand when they were photographed. Ryan Anderson, an anthropologist at Santa Clara University who has studied how Harrison appears in photographs, suggests that he made an intentional choice in how he presented himself. “He’s not portraying himself as an armed homesteader, and considering the situation, I don’t think that’s accidental,” Anderson says. “If a rumor starts going around that there’s this African American with a bunch of rifles, he probably doesn’t want to draw that kind of attention.” Mallios points out that, according to an 1854 California law that forbade the sale of firearms and ammunition to Native Americans or anyone associated with them, Harrison’s rifles and bullets were likely acquired illegally.

A number of artifacts unearthed in the excavations illustrate how closely connected Harrison was to the local Luiseño community. These include a small iron cross that helps corroborate historical accounts that Harrison was baptized by a Luiseño chief in Rincon who had converted to Catholicism. There were also two projectile points that had never been fired, suggesting to Mallios that they were likely given as gifts to Harrison by the Luiseño, as was a small pierced cylindrical greenstone pendant. Richard Carrico, an archaeologist and expert on Native Americans of Southern California at San Diego State University, notes that the Luiseño traditionally placed an arrow point in each corner of a house to induce good fortune.

Perhaps even more significant than the projectile points is the discovery just outside Harrison’s cabin of a portable granite metate, or grinding stone, that had been snapped in half. Carrico explains that metates deliberately broken in this manner were used by the Luiseño to mark the passing of tribal members, particularly women. “The Luiseño believe that the spirit of the woman is in that stone,” he says. “She spends days over her lifetime grinding seeds and plants, and some of her sweat and her oil and her spirit gets into that rock, so when she dies, it needs to be released.” Mallios acknowledges that it’s impossible to determine the true meaning of the broken metate, but suggests it may have commemorated the death of one of the Luiseño women to whom Harrison was married.

Yet another potentially hidden facet of Harrison’s story was revealed over a number of years, as the archaeologists recovered a series of implements associated with writing from his cabin: first a sharpened graphite pencil lead, then a pen cap and clip, and finally a number of eraser pieces. This accumulation of evidence hints that Harrison knew how to read and write, despite the fact that throughout his life, he signed many documents with an X, and every census record but one indicates that he was illiterate. The only exception is his final census, in 1920, when he was gravely ill in a hospital in San Diego. Mallios concedes it’s possible Harrison only learned to read and write in the last years of his life, but believes it’s more likely he was only comfortable revealing that he was literate once he had left the mountain. “I was intrigued by the idea that, what if all these years he had kept his literacy a secret and then only on his deathbed in the hospital does he let out that secret,” Mallios says. Like his decision to live on the mountain, Harrison’s motivation to conceal his literacy may have been self-preservation, points out Chuck Ambers, the founder and curator of the African Diaspora Museum and Research Center in San Diego, which was formerly known as the African Museum Casa del Rey Moro. “Reading and writing could be threatening,” says Ambers. “You have certain ex-Confederates in the area and there was always a thing about not teaching African Americans to read and write. I think Harrison hiding that he could read and write was part of his ability to appear nonthreatening.”

The realization that Harrison may have hidden his literacy until the very end of his life was just one of many instances in which Mallios was struck that Harrison had developed a carefully sculpted public persona that obscured or omitted key aspects of his identity. When entertaining travelers, Harrison came across as poorly educated, self-mocking, and folksy. “When I first came here dere was nobody but Injuns,” he would announce, according to tourist Allan Kelly. Harrison would then add, to his audience’s great amusement, “I was de fust white man on dis mountain.” But Mallios found a reference in Robert Asher’s account to a conversation in which Harrison, speaking confidently with no sign of his customary stylized vernacular, explained how to start a fire in damp conditions. “It was as if he had dropped the act,” says Mallios. Reflecting on another lengthy conversation with Harrison, Asher writes, “His language was such as I had been accustomed to all my life, that of a cultivated man.”

Although Harrison met his visitors unarmed and unmounted, the excavations have turned up hundreds of fired rifle cartridges and extensive horse tack. Among his neighbors, Harrison was known to ride a white horse, though there are no known photographs of him on horseback. Many personal items unearthed from his cabin—a meerschaum pipe, pocket watches and fobs, President-brand suspender clips—are visible in the photographs, but the greenstone pendant that was likely a gift from the Luiseño and the iron cross associated with his conversion to Catholicism are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps Harrison wore them under the clothing he received from his visitors.

Again and again, the explanation for these omissions seems to be self-protection. An unarmed, smiling African American man approaching on foot with an afternoon’s worth of tall tales about the backcountry was what people trekked up the mountain to see. A rifle-toting, clear-speaking African American homesteader glowering down from horseback, by contrast, was not. If Harrison were known to have been associated with Native Americans and Catholics at a time when the latter were being persecuted and the former removed from their land in the area, his position would have been even less tenable. “He presented the image he thought people wanted to see,” says Carrico. “You get the impression that he made them laugh and disarmed them, so when they left, they went, ‘That was fun. That was a good trip. He’s quite the guy.’”

Mallios points out that an African American man named John Ballard—a contemporary of Harrison who lived around 150 miles up the coast in Malibu—was received very differently by the white community. Like Harrison, Ballard was formerly enslaved. He too was brought west from Kentucky during the Gold Rush and made his way to Southern California, where he became a homesteader. “Ballard doesn’t put on the act the way Harrison does,” says Mallios. “He’s not deferential, he doesn’t make people comfortable—and they burn him off his property. This is the exact same time period when Harrison is at the height of his popularity. I don’t know if he was aware of Ballard, but he would have been so aware of the racial climate that he just developed this survival strategy.”

As far as anyone knows, Harrison never spoke of his time in slavery to the tourists who visited him or to his neighbors on the mountain, yet Mallios uncovered telling evidence that he carried memories of his origins with him to his California homestead. As the archaeologists excavated the remains of his cabin’s stone foundation, they found that the walls formed a square measuring just 11 feet on each side, an architectural style unknown in the area. Square structures of this size were, however, extremely common among slave quarters in the antebellum South. As at such slave quarters, the overwhelming majority of artifacts uncovered by archaeologists at the site of Harrison’s cabin came from the patio area, whereas the few items found in the cabin itself—including the writing implements, the unused arrow points, and the iron cross—tended to have greater personal importance. While Harrison could have built a much larger rectangular structure similar to those raised by other homesteaders on the mountain, he chose instead to replicate the sort of structure he likely knew as a child. “Maybe he carried with him the idea of what a house should look like, and that’s what he built there,” says Mallios. “But then again, maybe this was just part of his act.”

To read more about Nathan Harrison, see Born a Slave, Died a Pioneer by Seth Mallios.