Most historians and archaeologists agree: The sixth century A.D. was not an easy time to be alive. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed in the previous century, plunging much of the continent into economic, political, and social upheaval. On top of this, the first outbreak and frequent recurrence of bubonic plague resulted in the estimated deaths of millions. Making matters even worse, a series of volcanic eruptions caused climatic changes from Britain to China, ushering in a cooling period known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age. Recent studies have indicated that this caused drought, crop failure, breakdown in food supply chains, and famine. Harvard University medieval historian Michael McCormick has gone so far as to characterize the period following a particularly intense volcanic eruption in A.D. 536 as one of the single worst eras in recorded human history.

One consequence of this turmoil was that, across most of Europe, many urban centers deteriorated, a process that had begun a few centuries earlier when the Roman state first started to weaken. Cities and towns, once hallmarks of the Roman world and essential instruments of the Roman administrative system, were increasingly abandoned. Masses fled to the countryside seeking survival. Western civilization was irrevocably transformed.

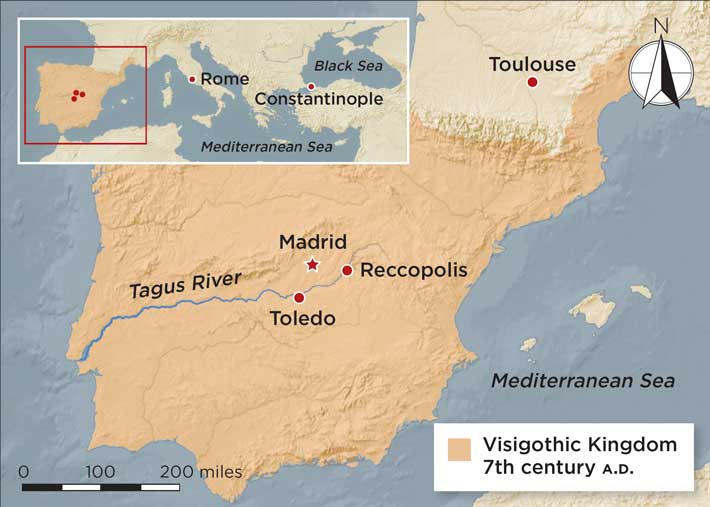

However, recent archaeological work in Iberia, on the periphery of the former Roman Empire, conveys a different story. It is revealing how, against this backdrop of chaos, a people emerged who succeeded in founding perhaps the strongest kingdom in the post-Roman world. These were the Visigoths, who had first arrived in Iberia in the A.D. 410s, when Roman rule was crumbling. Over the next two centuries the Visigoths unified a politically fractured landscape, bringing a semblance of stability to a region racked by centuries of violence and uncertainty. They implemented new taxation and legal systems and reestablished trade with the broader Mediterranean world. The Visigoths also did the seemingly impossible—in a largely deurbanized world, they began to build cities. Written sources suggest that the Visigoths founded at least four new urban centers, but only one of them, Reccopolis, can be identified with certainty. It was one of the crowning achievements of King Leovigild (r. A.D. 568–586), perhaps the Visigoths’ greatest ruler. Today, Reccopolis is an unlikely example of a post-Roman urban settlement that arose amid the disorder and uncertainty of sixth-century Europe. “One does not see many new towns founded during this period elsewhere in the Mediterranean,” says McCormick. “It is quite surprising.”

One Visigothic chronicler, John of Biclaro, records that Leovigild founded Reccopolis in A.D. 578 and furnished it with “splendid buildings.” Today, the remains of these buildings sit atop a plateau that rises above the banks of the Tagus River in the central Spanish province of Guadalajara. Although Reccopolis is less than a two-hour drive from Madrid, parts of this province have in recent years become some of the most desolate in all of Europe due to financial crises and a dearth of economic opportunities for its rural population. However, 1,400 years ago, the opposite process was underway. The establishment of a Visigothic settlement in the region attracted throngs of people who settled within the new town and formed satellite communities in its vicinity.

The walls and roofs of Reccopolis’ enormous palatine complex once towered high above the countryside, a ubiquitously visible symbol of the rising Visigothic state. Built on the city’s highest ground, this urban district served as the seat of the new Visigothic monarchy and administration. A church, one of the largest in Iberia at the time, was located across a large open plaza. A monumental gateway would have ushered people out of this district and onto a street full of shops and houses. Reccopolis was, by all accounts, a wealthy and vibrant city that was bustling in a way that very few others in Europe were. Yet, less than 250 years later, Reccopolis was nearly empty. Its building materials were hauled away to construct a new settlement, and over the subsequent centuries the once-great Visigothic city disappeared from view, receding into the surrounding agricultural fields.

The ruins of Reccopolis were located in the 1890s, but archaeological excavations did not begin until the mid-twentieth century. Work continued sporadically for decades, until interest began to intensify in the 1990s under the leadership of University of Alcalá archaeologist Lauro Olmo-Enciso. For more than two decades, Olmo-Enciso’s projects have continued to uncover parts of the ancient settlement that are not only leading to a new understanding of Visigothic cities, but also to a clearer picture of the physical and political landscape of post-Roman Iberia. “Reccopolis now stands as an exceptional example of early medieval urbanism that challenges our perceptions of urban development in sixth-century Europe,” Olmo-Enciso says. He and his team have learned just how integral urban centers such as Reccopolis were to the rulers of the Visigothic Kingdom, and especially to Leovigild. As it happens, the construction of Reccopolis was a strategic play that the king borrowed from the political handbook used by Roman emperors—the Visigoths’ old rivals—for centuries.

Who the Visigoths were and how they became kings of Iberia is a complicated story, the culmination of a journey that took place over hundreds of years and across thousands of miles. The group of people known today as the Visigoths, along with the culturally similar, but geographically separate Ostrogoths, were descended from the nomadic eastern Germanic Gothic tribes who, by the fourth century, had settled on the outskirts of the Roman Empire in modern-day Romania. In A.D. 376, migrations of Huns from the Eurasian steppes drove the Gothic communities across the Danube River and into Roman territory. Initially, the Romans granted them permission to seek refuge within the empire’s borders, but there was little trust on either side as the two groups had clashed regularly for decades along the Danube.

The Visigoths and Romans were at times allies, and at other times enemies. Inevitably, their tenuous relationship boiled over, leading to the Visigothic sack of Rome itself in A.D. 410, the first time the city had fallen to a foreign army in 800 years. Although by this time Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire, was the empire’s most important city, the Visigothic conquest of the Eternal City was a devastating blow, symbolizing the fragility of Roman rule in Western Europe.

In need of a homeland, the Visigoths soon settled in southern Gaul, in what is now France, and established a capital in modern-day Toulouse. By the early fifth century, they followed other marauding bands of Germanic barbarian tribes, including the Vandals and Suevi, over the Pyrenees into Iberia, where the Romans had almost completely lost control. After Rome’s final fall in A.D. 476, the Iberian Peninsula descended into a political free-for-all. “Historians and archaeologists imagine it as a welter of more or less autonomous, competing, and sometimes conflicting power centers and city-states,” says McCormick.

Out of this power vacuum, the Visigoths emerged to seize control. In the early sixth century, they lost most of their territory in Gaul to the Franks, but they began to expand and strengthen their hold on the former Roman province of Hispania, fighting a constant string of battles against other Germanic tribes, Hispano-Romano independent city-states, and Byzantine Roman armies who had managed to regain territory in southern Spain. By the final decades of the century, Visigothic forces, led by Leovigild, had proved themselves the dominant regional power. The king now needed a grand gesture to legitimize himself as the sole ruler of a unified Iberia. He also needed a reorganized administrative system to maintain authority over his now-vast territory. Like the Romans before him, he needed cities. So, like the Romans, he dared to build one.

In the more than six centuries during which the Romans ruled in Iberia, they transformed the peninsula into one of the most urbanized territories in the empire. But by the late sixth century only a handful of functioning cities remained. As Visigothic monarchs became more powerful, they began to revitalize cities and towns. Some effort was put into renovating and expanding already established centers such as Toledo, which became the capital of the new Visigothic Kingdom, but Leovigild and his successors also set out to build brand-new cities, an ambitious enterprise given the crisis conditions in most of Europe. “In the later sixth century, there were a startling number of developments which occurred that might seem unfavorable to creating new cities,” McCormick says.

If it was difficult and costly to rebuild existing cities, it was nearly unimaginable to attempt to build one ex novo, from the ground up. However, stone by stone, Reccopolis gradually began to rise above the plains of the Tagus River. “Reccopolis is the only example of state-sponsored urban development during the sixth and seventh centuries, not only in the Visigothic Kingdom but in all of Western Europe,” says Olmo-Enciso. “It is unparalleled.”

Although Visigothic craftsmanship, technological knowledge, and engineering skills were not as advanced as those of the Roman builders before them, the monumentality of Reccopolis is nonetheless impressive. “The founding of Reccopolis is surprising because of the scale of the project,” says University of Cambridge archaeologist Javier Martínez Jiménez, who has also taken part in the archaeological research there. The city was protected by a six-foot-thick defensive wall, which is preserved in some places to a height of 16 feet. This encloses an area of about 53 acres that safeguarded a population of as many as 2,000. Excavation within the walls has afforded archaeologists a glimpse of how Visigothic cities were conceived and designed. “Reccopolis is important because, as a new foundation, it reflects the urban ideals of the late sixth century,” says Martínez Jiménez. “It displays what cities might have been without a preexisting Roman skeleton.”

Reccopolis’ planners dispensed with many of the archetypal features of the classical Roman city. Reccopolis had no forum, no bath complex, no theaters, no circuses, nor any arenas for public spectacles. At the heart of the new Visigothic city lay the imposing palatine complex. This enormous compound was the center of civic, administrative, fiscal, and religious activities, and likely housed Reccopolis’ ruling aristocrats. It included a vast paved courtyard, a number of huge multistory buildings—the largest of which is more than 450 feet long—and a finely decorated Christian basilica. This quarter was separated from the rest of the city by the monumental arched gateway, one of the only examples of its kind in Western Europe, which led to the neighboring commercial district. Olmo-Enciso sees this aspect of Reccopolis’ topography as having been influenced by Byzantine urban models of the time. He believes that the combination of public square, civic and administrative buildings, elite housing, church, gateway, and adjacent shopping streets is a modest imitation of parts of some Byzantine cities, particularly of the area around the basilica of Hagia Sophia in the empire’s capital. “The planning and hierarchy of the urban design of Reccopolis refers to a conceptual model based on Constantinople,” Olmo-Enciso says.

Excavations outside the palatine complex have uncovered parts of the city featuring houses and industrial properties belonging to Reccopolis’ residents, artisans, and workers that underscore the city’s important role as a major fiscal and production center. Reccopolis was one of the few places in the Visigothic Kingdom that had its own mint, which issued gold coins on the crown’s behalf. Its main street was lined with shops, warehouses, and commercial establishments. There were two glass-blowing studios as well as a goldsmith’s workshop where archaeologists found scales and molds for crafting rings and earrings. Vendors sold imported luxury items, indicating that Reccopolis’ merchants were once again connected to broader Mediterranean trade markets, which had been largely closed off after Rome’s withdrawal from Iberia. “It is the richest collection of imports in the center of the Iberian Peninsula,” Olmo-Enciso says. “This shows that aristocrats and elites in Reccopolis had access to Mediterranean consumer goods.”

Reccopolis even had an aqueduct that brought water into the city from a source a few miles outside town. It is the only aqueduct built in Iberia during the Visigothic period. These constructed watercourses were essential to some Roman towns in Hispania, but most of them had fallen into disrepair in the post-Roman era and the technology appeared to have been lost. The Visigoths’ ability to construct a new aqueduct at Reccopolis is a testament to their wealth, determination, and engineering capabilities. “Very few cities in that period could claim to have an aqueduct,” says Martínez Jiménez. “There were no more than five other functioning aqueducts at that moment in Iberia, so it was a display of royal power and an element of civic pride for the inhabitants.”

First and foremost, Leovigild needed Reccopolis to help him maintain control over rural parts of the kingdom. “New urban foundations were established in areas where the monarchy had direct political interest and where there were no functional cities,” says Martínez Jiménez. “For the monarchy, cities were essential to the administration of the territory.” City building was also a huge financial, technological, and logistical undertaking and, as such, was extremely useful for benefactors’ self-promotion. A ruler had to secure the finances, the building materials, the labor force, the engineers, and a checklist of other items in order to pull off constructing and successfully maintaining a new city. “In the context of Central and Western Europe, the Visigothic Kingdom was the only one capable of undertaking operations of great importance such as the founding of a city,” Olmo-Enciso says. Leovigild also wanted something extraordinary to celebrate his tenth anniversary as ruler and his nascent and increasingly powerful Visigothic Kingdom. “If the monarchy needed to make a statement, it needed to have a city,” says Martínez Jiménez. “In addition to imposing control in a key territory in the core of the kingdom, there is a very important propagandistic component to Reccopolis.”

For Leovigild, there was an additional reason he needed to build a new city—it was what Roman emperors did. Although the Romans were their rivals, the Visigoths were nevertheless heavily influenced by the empire’s culture and symbols. After his rise to power, Leovigild began to portray himself in the manner of Byzantine emperors, adopting the clothing and royal vestments of his eastern counterparts. On coins that he had minted, he depicted himself wearing a diadem and a mantle, in the fashion of Byzantine rulers. For centuries, Roman emperors had built new cities or renamed existing ones after themselves or members of the imperial family as a way of advertising their authority and stamping their name on their territory.

Thus, as part of a deliberate program to emulate the behavior of Roman emperors, which scholars refer to as aemulatio imperii, Leovigild named his new city Reccopolis after his son and heir, Reccared. The message was clear. Leovigild was announcing himself as the founder of a new dynasty set to rule Hispania as an equal to the great Byzantines. “The founding of Reccopolis was a part of the monarchy’s display of power,” says Martínez Jiménez. “Founding a city is an imperial prerogative, so by building Reccopolis, Leovigild is ending the fiction that the emperor still had claims over Spain.”

Even though Reccopolis’ excavated ruins are impressive, some archaeologists remain skeptical about just how extensive the Visigothic settlement truly was. Excavations have been carried out for decades, but only around 8 percent of the total area within the city walls has been uncovered. The remainder, which is privately owned, has been inaccessible to archaeologists. Because large, well-developed urban settlements were such a rarity at this time, there have been questions about whether the rest of the site could actually have been as densely built up as the excavated areas have proved to be, and whether the grand descriptions of early medieval written sources were exaggerated. “We don’t really know whether the contemporary chronicler was describing Reccopolis in flattering terms as a city,” says McCormick, “when perhaps in reality, it was something more akin to a Potemkin village.”

McCormick and Olmo-Enciso recently used noninvasive geophysical methods to investigate what might be buried beneath the rest of the site. To their surprise, the images revealed additional streets, clusters of buildings, houses, terrace walls, and water channels, all of which are evidence of Reccopolis’ urban sprawl. They even identified a new sector of buildings belonging to the palatine complex. “We were all stunned to discover this completely unknown new quarter,” McCormick says. “Most of the area inside the walls had buildings, showing that this was a built-up town of significant dimensions for this period.”

The survey not only revealed that the settlement extended throughout the walled area, but also showed that small communities had been established outside the walls. “We had hoped there might be a suburban zone, but who knew?” remarks McCormick. “And there it was.”

Despite its prosperity under Leovigild and his successors, Reccopolis began to decline just a century after it was founded. By the late seventh century, internal conflicts plagued the Visigothic Kingdom’s leadership, and Iberia was overrun by the North African forces of the Umayyad Caliphate in A.D. 711, effectively ending Visigothic rule. In the immediate aftermath, Reccopolis continued to be an important town, but that was short-lived. The recent geophysical survey detected the outlines of a mysterious building that seems to resemble contemporaneous Umayyad mosques. Further exploration is needed, but it’s possible that these remains represent one of the first mosques ever built in Iberia.

In the early ninth century, a new Muslim administrative center was founded less than a mile upstream from Reccopolis at Zorita de los Canes, condemning the former Visigothic city to obsolescence. Reccopolis’ buildings were gradually dismantled and the stones reused to build the new Umayyad citadel. Although excavations have barely begun to reveal the ancient city’s whole story, Reccopolis is a unique archaeological site that has the potential to produce invaluable information about a flourishing city during a still little-understood period of the European Dark Ages. “It is to date the only Roman-style town founded by a Germanic successor society on Roman soil that has been identified and excavated,” says McCormick. “In many respects, Visigothic urban archaeology is in its early stages, but Reccopolis offers a whole new chapter in the understanding of Romano-barbarian kingdoms after the fall of Rome.”