Stephen H. Lekson is a curator emeritus of archaeology at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History and has excavated in the American Southwest for almost 50 years. He first contributed to ARCHAEOLOGY in 1990. Among his articles is “Rewriting Southwestern Prehistory” (1997), in which he first articulated the novel “Chaco Meridian” theory, which holds that successive regional capitals in the Southwest were established in relation to one another according to precise geographic coordinates. Here, Lekson tells the story of his latest visit to the Chaco Meridian’s southernmost end.

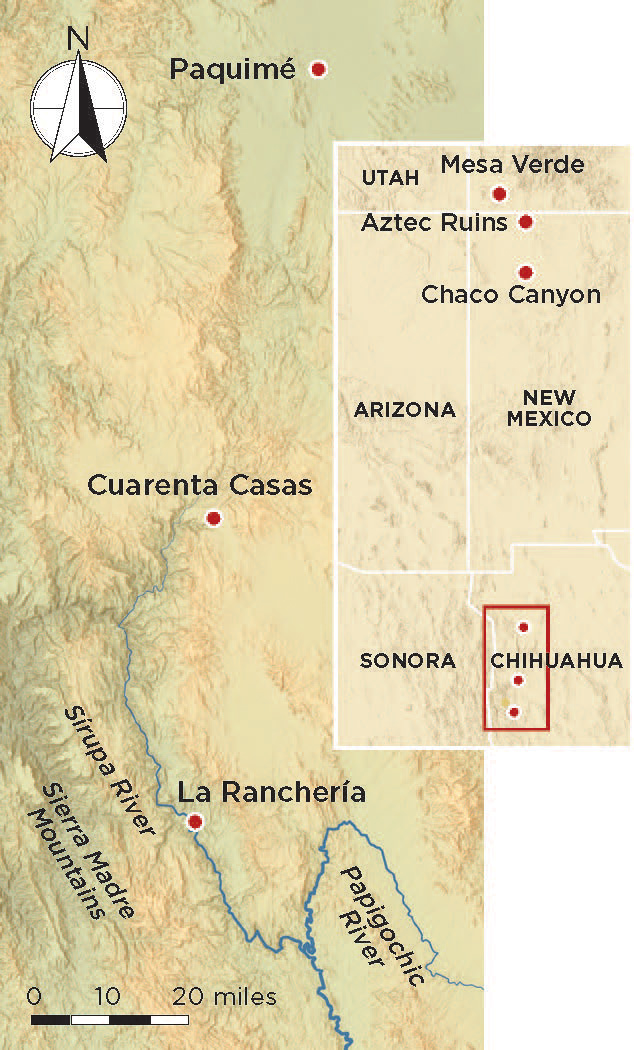

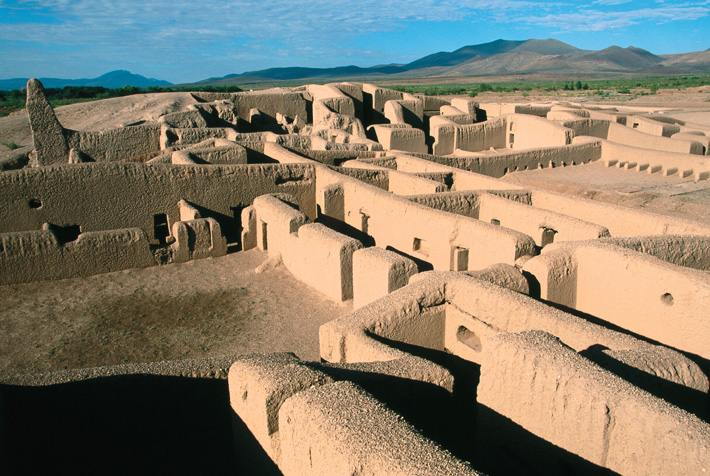

Outside the town of Madera in the Sierra Madre, some 130 miles west of Chihuahua City in northern Mexico, canyons cut deep into the mountains. Here, in caves and alcoves and on ledges high up the canyon cliffs, the white walls of ancient dwellings stand out against green scrub. Like the cliff dwellings of Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park, those in the Sierra Madre made up small villages peripheral to a great political center. For the villages of Mesa Verde, that center was the site of Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico; for those in the Sierra Madre, it was Paquimé, a city that lay some 60 miles to the north in the plains that lie east of the mountains. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Paquimé, also known as Casas Grandes, was ruled by people who held sway over a region about half the size of Ohio. The cliff dwellers of the Sierra Madre lived on the western fringes of that expansive territory.

In a cave near the head of one these long canyons is a cliff dwelling called Las Ventanas, or The Windows, named for the many tiny fenestrations of one of its 30 rooms. The site is at the center of a cluster of cliff dwellings together called Cuarenta Casas, or Forty Houses. Las Ventanas is the largest of that group, and one of the largest ever built in the Sierra Madre. In places it was two stories tall, the second-story walls reaching the cave’s roof. Where the second-story walls have collapsed, their outlines remain on the smoke-blackened ceiling, like ghostly negative wall plans. Like most Sierra Madre cliff dwellings, Las Ventanas is constructed of adobe, which is made by pouring mud into plank frames and ramming it into wide courses. The builders repeated the process to raise each story’s walls five or six feet high. Many of these dwellings feature large, T-shaped doors, unusual portals to which their builders may have ascribed ideological or political importance, and whose possible significance drew me to the Sierra Madre.

In the fall of 2019, I was one of five American archaeologists joining a small group from Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Colorado on a visit to the cliff dwellings in the Sierra Madre. Travel in Chihuahua’s mountains is challenging. The region has a violent history: Apache raiding parties and Pancho Villa’s guerilla army traveled through the mountains’ barrancas, or narrow river gorges. Today, drug cartels have staked their claim here. The people we met, the villages we saw, and the farms and ranches we drove through were busy and prosperous, but, we were told, all were haunted by the threat of cartel violence. Our guides, from Alianza Mesoamericana de Ecoturismo, were informed and careful, and we encountered no problems.

We were joined by archaeologist Eduardo Gamboa of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, who directed a decade-long study of 180 cliff dwellings in Chihuahua. He is currently writing what will surely be the definitive study of these fascinating sites. Only a few archaeologists preceded Gamboa in studying these cliff dwellings. One of the first was Carl Lumholtz, a Norwegian explorer in the employ of the American Museum of Natural History. Lumholtz explored the Sierra Madre in the 1890s and photographed a large T-shaped door at Las Ventanas. I’d studied the images in Lumholtz’s book, Unknown Mexico, and this big, bold T-portal intrigued me.

More than 60 percent of the doors at the power center of Paquimé are T-shaped. Most are fairly small, measuring less than four feet tall and just two feet wide. But 20 are much larger, measuring over five feet tall and four feet wide. Like those at Las Ventanas, Paquimé’s large T-doors are almost all located in exterior walls. According to Gamboa, that was also the case in many other cliff dwellings of the Sierra Madre. I wanted to see these T-doors in the mountains for myself.

We first glimpsed Las Ventanas from a little under half a mile away, from the opposite rim of the canyon. Hiking 600 feet down to the canyon’s bottom was easy, but scrambling 200 feet back up the canyon wall on the other side to the site was a challenge in the thin mountain air. Once we had reached Las Ventanas, we discovered that sometime since Lumholtz took his photographs, the right side of the large T-door had toppled. But its left side still stands, preserving its shape, with which I was very familiar from years of archaeological work at sites 500 miles to the north, in the American Southwest.

T-shaped doors are prominent not just at Paquimé and the Sierra Madre cliff dwellings, but also at Ancestral Puebloan sites in the Four Corners region, where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet. I thought this curious distribution, with such a great distance between the two concentrations of T-shaped doors, had to be meaningful.

The doors were first constructed at Chaco Canyon, the eleventh-century capital of a region in today’s New Mexico. Chaco itself was small—perhaps only about 3,000 people lived there. The site was nevertheless monumental, and had a dozen palatial so-called Great Houses, three- to four-story masonry buildings where its ruling elite lived. Chaco’s leaders controlled a large area—about the size of Indiana—that was home to between 60,000 and 100,000 people. The site was abandoned in the twelfth century, and the capital shifted 50 miles north to what is today Aztec Ruins National Monument. Aztec Ruins became the center of a newly resettled region that included the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, about 40 miles away. The T-doors at Aztec Ruins are echoed by scores of T-doors at Mesa Verde and other smaller cliff dwellings in the area.

Between 1250 and 1290, tens of thousands of people left the Mesa Verde region, perhaps fleeing political unrest and widespread violence to resettle in villages where Pueblo peoples still live today, in an arc from the Hopi settlements in Arizona through the villages of Zuni and Acoma to a dozen pueblos along the Rio Grande in New Mexico. The T-doors of Chaco and Mesa Verde ceased to be made in the Pueblo area after 1300. But they appeared, in great numbers, between 1250 and 1300 at Paquimé and the cliff dwellings of the Sierra Madre.

Twenty-five years ago, I suggested that Chaco Canyon, Aztec Ruins, and Paquimé were three sequential, historically linked capitals governing sizable regions in the greater American Southwest. The evidence for their historical connection was primarily distinctive architectural details associated with social hierarchy that were found only in these three areas. Public colonnades, a Mesoamerican feature, faced plazas where ceremonies could have taken place for all the community to see. Many important structures had a very particular form of built-in bed, which only those who occupied the buildings would have seen. And all had secret features, including stacks of huge sandstone disks, foundations set below key pillars, and posts that were far in excess of structural requirements. Only the builders would have known about these types of dedicatory offerings.

And the people who laid out the three capitals also shared an obsession with cardinal directions decidedly unlike those who planned other villages and towns in the greater American Southwest. In fact, the three sites were located more or less north–south of each other on a broad longitude I call the Chaco Meridian. This wasn’t an accident. A linear earthen monument archaeologists call the Great North Road runs due north from Chaco to Aztec Ruins, linking the two—history written on the ground.

While the three capitals were almost precisely sequential in time and space, each had its own particular traits. The people at each site produced their own pottery: the thin-slipped black-on-white of Chaco, the richly polished black-on-white at Mesa Verde, and the colorful red, black, and tan polychromes of Paquimé. The people living at all three capitals had their own stories, but they were surely linked by history and ideology.

I noted that T-shaped doors existed at all three sites, but I wasn’t sure what to make of them, or how they related to social hierarchies. After all, T-doors have been found at many sites beyond the respective capitals—most obviously at cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde and the Sierra Madre. At Chaco Canyon, the doors were found exclusively in the Great Houses. But at Aztec Ruins and Mesa Verde, and in the Casas Grandes region, the T-doors were “democratized” and used in residences where both high-status and common people lived.

Generations of park rangers at Mesa Verde told tourists that the T-shape was somehow practical—handy if you had a pack on your back—but the shape clearly had an important ideological meaning. At Mesa Verde, cliff dwellers cut tiny T-shaped openings into the handles of their pottery vessels. Paquimé’s leaders ordered the construction of two carefully carved stone altars centered on sculpted T-shaped openings. The big T-shaped doors facing conspicuously outward from the front walls of Mesa Verde and Sierra Madre cliff dwellings sent a message: Behind this door live people who hold the T-shape in high esteem. What that shape meant to them is unknown. Scholars have suggested the T-doors resemble a rattlesnake’s tail, or the Hopi deity Masauwu, or even a Mayan glyph. We may not know their precise meaning, but it’s clear they meant something. And if I am right about the Chaco Meridian, these T-doors might mirror the history of movements of political power in the ancient Southwest.

After our scramble to reach Las Ventanas, we visited more cliff dwellings in the headwaters of the Papigochic River, known locally as Río Aros, at the southern edge of the Casas Grandes region. The gravel roads leaving Madera were good. But after a few miles, those roads turned into narrow dirt logging tracks, twisting and turning in and out of barrancas. Lumber trucks surprised us around too many curves, but our local drivers knew their business and we arrived intact, with a slight surplus of adrenaline.

The winding road brought us to the rim of the Huápoca Gorge of the Papigochic River, which is two-thirds of a mile deep. We roped down a steep chute to Cueva de la Serpiente, the Cave of the Serpent. The site’s 14 rooms fill a cave that tunnels through a rocky buttress that projects out from the canyon wall, which gives the cliff dwelling both front and back entrances. The more approachable entrance has a big T-door framed by a painting of a serpent, now faded to a few traces of pigment. The sheer side of the dwelling has several T-doors, in exterior walls opening into rooms behind.

An easy hike along the barranca’s bottom led to Cueva Grande, an exceptionally large cave behind a seasonal waterfall. There, lush vegetation at the bottom of Huápoca Gorge contrasted sharply with the arid pine forests on the heights far above. The thick-billed parrots who live here had flown south for the season, but it was easy to imagine brightly colored tropical birds fluttering around the waterfall. With a floor area of more than 6,300 square feet, the cave features three separate two-story structures. The two deeper in the cave are in ruins, but the front structure stands more or less intact. Its exterior wall, facing our approach from the valley bottom, has a T-door on the second floor. Here, too, the T-shape clearly meant something to the people who called it home.

A jarring four-wheel-drive truck ride followed by a healthy hike along pre-Columbian irrigation ditches then led us up to the site of La Ranchería, some 20 miles upstream in the Sírupa Gorge of the Papigochic River. The cliff dwelling there is large, with more than 20 rooms along the back of an alcove that has a leveled terrace or plaza in front of it. Large T-doors open onto the terrace and are conspicuous from below. The walls of one room are covered with remarkable murals, black-brown pigments in complex geometric patterns, and on one wall, an image of a fish. We found sherds of Casas Grandes polychrome pottery that Gamboa, who had supervised excavations at La Ranchería for three years, had not previously seen. This small but important discovery linked the backwoods cliff dwelling to the distant, sophisticated capital city.

On the plaza of La Ranchería, we gathered around the surviving adobe support column of a granary, a feature particular to cliff dwellings of the Sierra Madre. This example resembled an overgrown adobe birdbath, stout as a barrel and waist-high. It once supported a mud-covered wicker granary, now gone. But many large, freestanding granaries are more than five feet tall, and were an important feature of the cliff dweller’s daily life. We saw more spectacular examples of granaries 50 miles north of the Papigochic River sites in an area known as Cave Valley, a scant 25 miles west of Paquimé as the crow flies, though that bird would have to fly over the 2,500-foot-tall jagged front range of the Sierra Madre.

Cave Valley is a broad fertile bottomland flanked by 150-foot-tall bluffs stretching two miles along the Río Piedras Verdes. Its agricultural potential attracted not only the ancient cliff dwellers but, much later, a small farming settlement of nineteenth-century Mormon immigrants. In 1952, 37-year-old archaeologist Robert Lister led a dozen University of Colorado students into Cave Valley, where they located 10 caves that had seemingly been picked clean by looters. Lumholtz had complained of “relic-hunters” when he visited Cave Valley a half century earlier. Only a few potsherds and corncobs remained on the surface. But Lister’s team unearthed many more artifacts, which are now housed at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History.

At a cliff dwelling known as Rincón Cave, Lister’s students pieced together half of a Casas Grandes pot—one of the few bits of direct evidence that the cliff dwellings were contemporary with Paquimé. Lister also investigated a sizable cliff dwelling with prominent T-doors known as Cave of the Olla. This site’s most striking feature is a graceful onion-dome-shaped central granary, probably the best-preserved example in the Sierra Madre.

Lister and his crew’s most significant excavations were in Swallow Cave, high on the bluff across the river from Cave of the Olla. There, Lister dug a small trench right next to a single remnant of wall and found a floor, beneath which was the burial of an adult woman interred with an early, pre-Paquimé red-on-brown pot. The discovery of a burial containing an artifact predating the rise of the great city suggests that some of the cliff dwellings may have been built before Paquimé was established. That possibility is also literally written on the roof of other caves, such as Cave of the Olla, where outlines are visible of earlier “ghost walls” that do not align with the cliff dwellings that can be seen there today.

After visiting a dozen cliff dwellings in the Sierra Madre, I was still left wondering about their origins—who built them, and why? Those at Mesa Verde, dating to the century before Paquimé’s rise around 1250, were clearly built for defense. Bad times, involving high levels of violence among villagers, drove Mesa Verde’s people into inaccessible alcoves, and eventually away from their homelands. We found it challenging to reach some of the Sierra Madre cliff dwellings, which suggests they might have been built for defensive purposes. But in Cave Valley we walked easily into the big dwellings in Olla and Rincón Caves. The granaries that stored critical food reserves are located everywhere in the valley, conspicuously placed along the fronts of the caves, and not behind dwellings in the secure rear of the alcoves. And some cliff dwellings are located near contemporary villages that lie on the valley floor, suggesting the people living in the Sierra Madre were not worried about defending themselves.

Perhaps, over the many decades the dwellings were occupied, their purpose shifted. Gamboa suggests the pre-Paquimé cliff dwellings might have been built in the early thirteenth century, after an influx of new people arrived from the north fleeing violence. Perhaps they brought the concept of T-doors with them. They may have built these dwellings as defensible homes—like those of Mesa Verde a few decades earlier—until the rise of Paquimé put an end to unrest.

With the establishment of Paquimé, the cliff dwellings may have functioned as base camps for people exploiting the game, timber, and mineral resources of the uplands. Or they may have been way stations along trade routes, given the remains of tropical macaws and large quantities of exotic Mesoamerican goods such as elaborate copper artifacts found at Paquimé. Perhaps the highly visible granaries were a welcome sign for hungry travelers. And, after the fall of Paquimé around 1450, which may have been violent, some of the considerable Casas Grandes population surely sought refuge in the barrancas of the Sierra Madre. There they might have found shelter in cliff dwellings with their familiar T-shaped doors, which were perhaps the last and most spectacular expression of a long history that began in Chaco Canyon and ended at Paquimé.