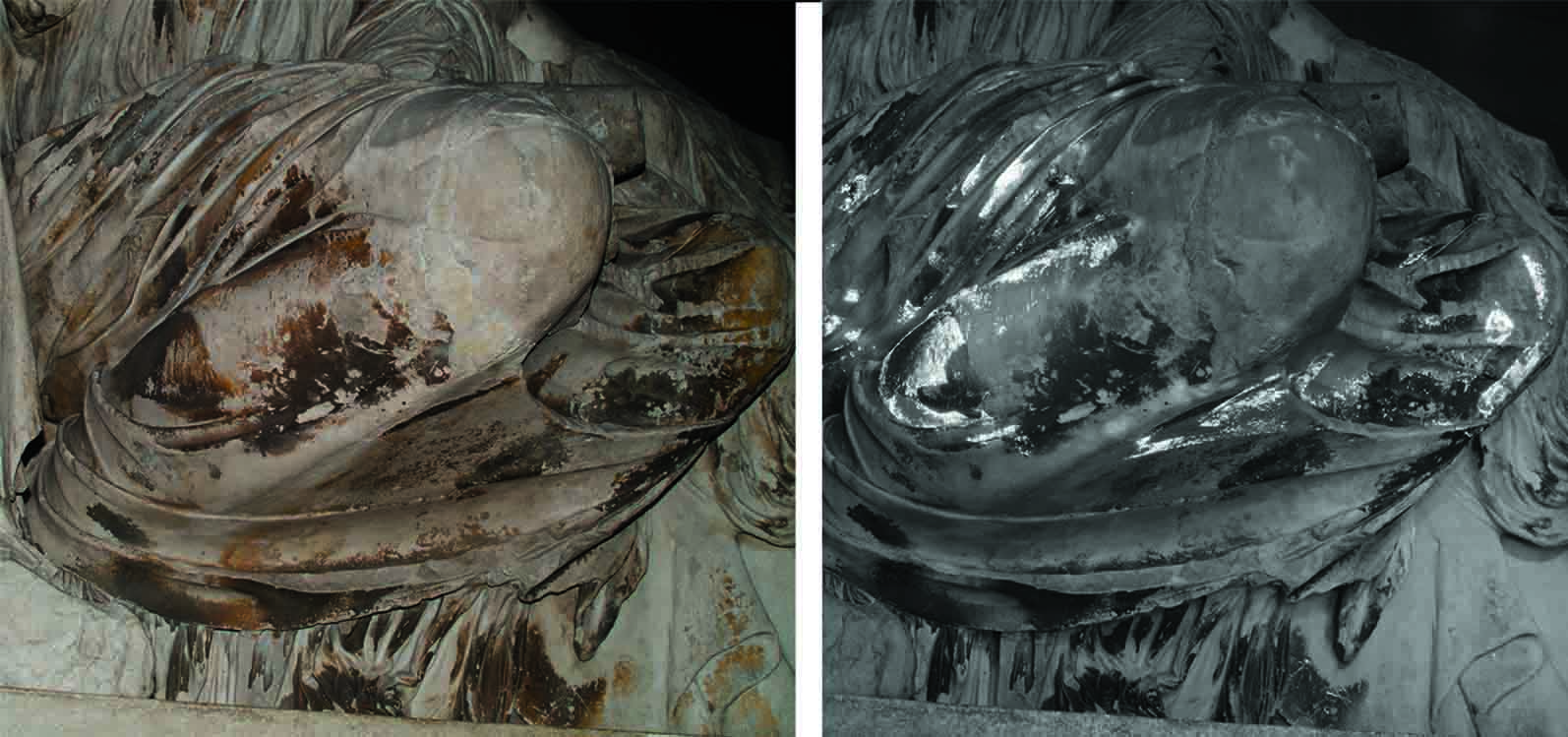

Evidence that many sculptures from antiquity were not the bright white marble that people imagine today but were originally painted in various colors that have worn away over the millennia has been amassing for decades. Researchers have now found the first traces of paint on the marble sculptures held at the British Museum that came from the Parthenon, the temple to Athena that was built on the Athenian Acropolis in the fifth century B.C. A team led by Giovanni Verri, a conservation scientist at the Art Institute of Chicago, used a technique called visible-induced luminescence imaging to document extensive traces of Egyptian blue, a pigment containing lime, copper, and silicon, on the surface of some of the sculptures. This involved exposing them to red or green light, which causes even the smallest particles of the pigment to emit infrared radiation that can be detected using a digital camera.

Egyptian blue appears to have been used on the Parthenon to depict several characteristics. The color represents water, from which Helios, the god of the sun, is shown rising with his chariot. It also seems to denote empty space or air, as in the area between the legs of stools on which the goddesses Demeter and her daughter Persephone sit. Most extensively, Egyptian blue was used to depict designs on woolen garments. A particularly elaborate example is found in the mantle of a figure believed to be the goddess Dione. Along with Egyptian blue, small particles of a purple color were also identified. Verri emphasizes that it is still difficult to say exactly how the artworks would have appeared when first put on display. “The attention and level of complexity that went into carving the sculptures is easily recognizable,” he says. “I would say that the same level of complexity and care went into the painting.”

To see a video about this work, click below.