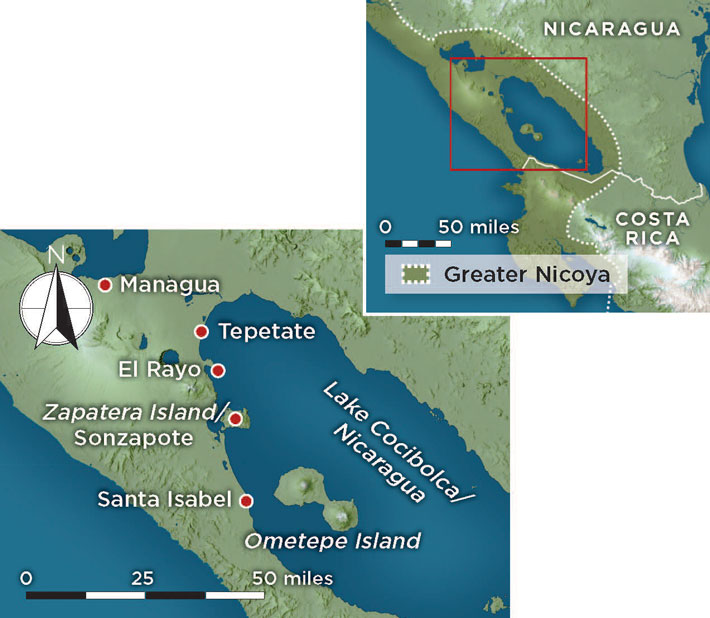

Rising from the middle of Lake Cocibolca—also known as Lake Nicaragua—the largest lake in Central America, dumbbell-shaped Ometepe Island is formed by two volcanoes joined by a narrow isthmus. The twin peaks of Volcán Concepción and Volcán Maderas are often covered in thick clouds. But on a clear day, the view to the east from the top of either volcano takes in thick jungle that extends some 100 miles all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. To the west, a narrow strip of fertile plains separates Lake Cocibolca and the Pacific Ocean. South lies Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula, divided from the rest of the country by the Gulf of Nicoya.

For thousands of years, this region, known as Greater Nicoya to modern scholars, served as a natural crossroads for cultures from as far away as central Mexico and South America. In the early sixteenth century, when Europeans first arrived in the area, the people living in Greater Nicoya spoke languages that belonged to three distinct families, including two that were closely related to Mesoamerican languages spoken to the north. In 1519, Spaniards Juan de Castañeda and Hernán Ponce de León led an expedition that put in at the Gulf of Nicoya and was met by a party of armed Chorotega warriors. The Spaniards noted that the Chorotega language was related to ones spoken in the south-central Mexican highlands, some 1,300 miles away.

Three years later, Spanish officer Gil González Dávila was dispatched as the head of an expedition from the newly founded colony of Panama to subdue the people of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. His force encountered the Indigenous Nicarao people, who drove the Spaniards back. The Nicarao lived between Lake Cocibolca and the Pacific coast and spoke a language related to that spoken by the Aztec, or Mexica, people of central Mexico.

When the Spaniards returned to the region within a decade, they came into contact with speakers of dialects of the Chibchan language family. Languages belonging to this family were once spoken throughout much of Central America, from Honduras to northern Colombia, and are thought to be related to those spoken by people who first arrived there many thousands of years ago.

Greater Nicoya’s Indigenous population fell drastically in the wake of contact with the Spanish. Today, Native peoples make up about 10 percent of Nicaragua’s population, and less than 3 percent of Costa Rica’s. Their ancestors left behind colorful painted pottery, intricate rock art, and life-size stone sculptures, but nothing like the monumental constructions that marked the cities of the Maya and other Mesoamerican peoples. Archaeologists first started to investigate Greater Nicoya in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the region is still one of the least archaeologically explored in the Western Hemisphere, according to archaeologist Geoffrey McCafferty of the University of Calgary. “Our understanding of Nicaraguan prehistory remains rudimentary, with significant gaps,” he says. The fact that the Nicarao and Chorotega peoples in the region spoke languages closely related to those spoken in Mexico led twentieth-century scholars to assume that southward migration of Mesoamerican peoples was largely responsible for Greater Nicoya’s vibrant culture.

But archaeologists working on projects over the past two decades, many of which have been directed by McCafferty and his colleagues as well as Nicaraguan and Costa Rican archaeologists, have begun to find evidence that contradicts earlier assumptions about the history of Greater Nicoya. “It’s a much more dynamic area than we thought previously,” says archaeologist Silvia Salgado of the University of Costa Rica.

People living in regions at the edges of major cultural areas such as Mesoamerica are often thought to be backward, almost by definition, says archaeologist Carrie Dennett of Red Deer Polytechnic. “It’s the idea that somehow people can’t exist without some kind of big powerful group telling them who to be,” she says. “So anything they do is because of some kind of external influence rather than internal developments.” In the case of Greater Nicoya, she says, recent discoveries show that perception clearly needs to change.

The most detailed descriptions of Greater Nicoya’s Indigenous cultures come from Catholic priests such as Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, who interviewed community elders and recorded linguistic patterns and cultural practices in the decades after the Spanish conquered the people of what would become Nicaragua. These histories describe at least two waves of migrants who came from central and southern Mexico and settled along the Pacific coast and western shore of Lake Cocibolca.

According to these Spanish records, the Chorotega arrived in about A.D. 800 and spoke a dialect of Oto-Manguean. This language family includes those spoken in the south-central Mexican highlands by the Mixtec people, as well as the Zapotecs, who established some of Mesoamerica’s earliest urban centers beginning in the sixth century B.C. The Nicarao spoke a Nahuan language akin to those spoken by the Toltecs and Mexica of central Mexico. Oto-Manguean speakers eventually controlled most of Pacific Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica. The Nicarao lived in smaller interspersed areas on the shores of Lake Cocibolca and, farther north, the Gulf of Fonseca bordering El Salvador. Chibchan speakers were concentrated near the Nicoya Peninsula.

Despite this complex linguistic landscape, archaeologists accepted a relatively simple picture of Greater Nicoya’s history well into the twentieth century. They assumed the Chorotega arrived at the start of the Sapoá period, which lasted from about A.D. 800 to 1350 and is named after a river valley in northwestern Costa Rica. They were followed by the Nahua-speaking Nicarao, who migrated to the region at the beginning of the Ometepe period, which lasted from around 1300 to 1525 and is named for the island in Lake Cocibolca. Scholars believed these Mexican migrants brought their own languages and cultures with them and almost completely displaced local populations of Chibchan speakers.

Although archaeological evidence supporting this chronology was scant to nonexistent, the “out of Mexico” hypothesis led to a tendency among scholars to treat Greater Nicoya as a homogeneous southern extension of Greater Mesoamerica. But a new generation of archaeologists started to question whether Greater Nicoya really was just a frontier outpost of more advanced cultures. They began to search for archaeological data to support the ethnohistoric accounts of the origins of the people of Greater Nicoya.

In the early 2000s, McCafferty, along with other archaeologists from the University of Calgary, launched more than a dozen projects on the shores and volcanic islands of Lake Cocibolca. It was the most intensive archaeological research ever conducted in Nicaragua and focused on sites that were thought to have been occupied during the later Ometepe period.

Santa Isabel, on the west side of Lake Cocibolca, near the modern city of Rivas, was said to have been the Nicarao capital when the Spaniards arrived, with a teyte, or ruler, known as Nicaragua. The settlement of Tepetate, at the northern edge of the lake, also had a large Indigenous population when Spanish officer Francisco Hernández de Córdoba founded the city of Granada there in 1524. Archaeologists discovered that Tepetate had been badly looted, in contrast to El Rayo, a well-preserved site on a peninsula extending into the lake nearby. The team also investigated a site on Zapatera Island, in Lake Cocibolca, called Sonzapote, as well as five sites on Ometepe Island.

Two decades of investigations revealed a detailed picture of the lives of Nicaragua’s Indigenous inhabitants. They fished using nets with ceramic weights and bone hooks, and cleaned animal hides with stone scrapers. They crushed palm nuts and seeds on grinding stones made of basalt and andesite and produced wine from the jocote fruit. Archaeologists unearthed thousands of fragments of pottery decorated with intricately painted and engraved designs. Among them were pots called cazuelas that ancient people likely used to cook stews of wild plants and animals.

The researchers also found hundreds of beads and pendants made from clay, bone, and shell, along with the perforated teeth of peccaries, jaguars, and sharks. They uncovered painted figurines, typically portraying women, whose style changed over time. Those dated to before the Sapoá period tend to be monochrome, while figurines made after A.D. 800 are depicted wearing multicolored clothing. Both types of figurine were found at Santa Isabel, possible evidence of cultural mixing between groups who had lived in the region for thousands of years and later immigrants.

Rock art is abundant throughout the region, and includes petroglyphs depicting geometric motifs, abstract shapes, and images of human figures and animals such as birds, monkeys, and caimans, as well as jaguar paw prints. A 17-year survey of rock art on Ometepe Island led by Suzanne Baker of Archaeological/Historical Consultants identified at least 2,000 petroglyphs at 116 sites.

Traces of architecture at Greater Nicoya sites were among the first discovered in Nicaragua to show that Indigenous groups lived in long-term settlements. Fragments of wattle-and-daub walls at Santa Isabel are evidence of residential structures, and multiple layers of compacted sand flooring showed that inhabitants rebuilt their homes every 30 to 50 years. Archaeologists interpreted stone constructions at Sonzapote and El Rayo as civic or ceremonial buildings, the first such public structures identified in the region.

While working at Sonzapote, McCafferty led a team that mapped 17 rectangular mounds built of blocks of igneous rock that rose up to 10 feet high. The absence of domestic refuse and the mounds’ location around areas that could have been plazas suggest the inhabitants were experimenting with early forms of urbanism before people in other regions of Central America, he says.

Excavations at El Rayo revealed a double row of vertical stone slabs that formed one wall of a structure that measured about 80 by 30 feet. Since they uncovered very few artifacts in the structure, researchers think it may have been connected with scattered human skeletal remains and shoe-shaped burial urns unearthed nearby. The urn burials are similar to contemporaneous ones found at Santa Isabel, McCafferty says, but are a dramatic departure from earlier, simpler mortuary practices identified at sites near Managua, today’s capital of Nicaragua.

The wealth of new detail that archaeologists found about the lives of the people of Greater Nicoya, however, was almost overshadowed by what they didn’t find. Out of more than 60 radiocarbon samples from more than a dozen projects, all but one dated to before 1300. Researchers had thought that Santa Isabel was occupied until European contact, presumably by the Nicarao, in part because the site contained ceramics that had been ascribed to the later Ometepe period. But 17 samples from the site were all dated to between A.D. 686 and 1280, corresponding to the Sapoá period and the Chorotega cultural group instead. Dates from Tepetate and El Rayo were also all before 1300.

The single Ometepe-period date came from one of the five sites on Ometepe Island, from a precontact-style burial urn that also contained colonial-era glass, indicating the urn must have been buried after the first encounters between the people of Greater Nicoya and the Spanish. “I was frustrated that I didn’t find what I was expecting,” McCafferty says. “We never found any sites relating to the final two hundred or three hundred years before the Spanish arrived,” when it had been assumed the Nicarao migrated from southern Mexico. “We actually found a lot of contradictory information,” he adds.

The cumulative evidence of the University of Calgary projects showed that virtually all the sites in Greater Nicoya that researchers thought were from the Ometepe period were actually centuries older. Artifacts such as pottery that were assumed to be the work of the Nicarao were actually from the Chorotega era. Those results raised questions about the timing of migrations and the influence of Mesoamerican culture on Native Chibchan speakers.

Clear signs of links between Mesoamerica and Greater Nicoya include images on polychrome pottery dated to the Sapoá period that are similar to the stylized animals and gods on the 260-day sacred calendar of the Mixtec. Other pottery from Greater Nicoya features images of the Mesoamerican wind god Ehécatl and the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl. A large ceramic sphere found at Santa Isabel bears a carved face with goggle-shaped eyes and fangs, attributes associated with the Mexican storm god Tlaloc.

But other elements from Mesoamerican culture are missing from the archaeological record in Greater Nicoya. Archaeologists have thus far found no comals, the large griddles used to heat tortillas that are abundant in Postclassic period (ca. A.D. 900–1519) sites in central Mexico. They also have not identified any maize, a staple of the Mesoamerican diet, among the hundreds of carbonized seeds unearthed at sites in Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Nor were there turkey or dog bones among the hundreds of thousands of animal remains from these sites, although evidence of the two species is abundant in Mesoamerican settlements.

Scholars even began to rethink the origins of what appears to be Mixtec-style imagery on Greater Nicoya pottery. The Mixtec themselves didn’t adopt codex-style painted pottery—with designs that resemble Postclassic Maya codices painted on bark paper—until the Late Postclassic (1200–1519). This suggests that craftspeople in Central America may have played a role in developing this style rather than passively adopting an imported tradition. “We need to seriously consider the possibility that the Nicaraguan potting tradition is actually of Indigenous Central American origin,” says archaeologist Larry Steinbrenner of Red Deer Polytechnic. Rather than being a colony of Mesoamerica, or just accepting Mesoamerican innovations, he says, Greater Nicoya might have contributed to a ceramic tradition shared along Mesoamerica’s periphery in El Salvador and Honduras, and perhaps even extending farther north into Maya territory. “We’ve always assumed that the affinities we see are the result of diffusion from north to south,” Steinbrenner says. “But who’s to say the influence didn’t run in the other direction, with potters on the periphery taking their cue from ceramic innovations that first developed in the south? Maybe it was the potters of Greater Nicoya who inspired the Mesoamericans, rather than the other way around.”

It appears that Mesoamerican influence on Greater Nicoya has been overemphasized at the expense of the region’s Indigenous cultures, says archaeologist Alexander Geurds of the University of Oxford. He adds that the “out of Mexico” hypothesis may have once been a straightforward explanation to understand the region’s material culture. “But our interpretation has become more nuanced,” Geurds says. “There’s obviously lots of local things going on as well. Perhaps those might have been the dominant thread in terms of how material culture developed.”

While McCafferty still believes Mexican cultures had some influence during the Sapoá period, he does not think that they replaced local Chibchan-speaking populations, as the linguistic evidence had led scholars to assume. “I don’t have anything that I can point to and say, ‘Here’s clear evidence of actual Mexican populations in the area,’” he says. Whether many, or even just a few, Nahua-speaking people migrated from Mexico to Greater Nicoya during the Ometepe period is an open question. “Assuming the linguistic data is correct, then there’s something going on that isn’t well reflected in the archaeological record,” McCafferty says. “The Nahua migration from Mexico is still a mystery supported by linguistics, but not the archaeology.”

As archaeologists continue to search for the origins of the people of Greater Nicoya, what they discover will resonate in present-day Nicaragua, where historical links to Mesoamerica have been a point of pride. “One of the big questions that a lot of us aspiring Nicaraguan archaeologists consider when we start is ‘Who were they and how did they make it here?’” says archaeologist Manuel Roman-Lacayo of the University of Pittsburgh. But he, too, says that recent findings are causing a broad shift in perceptions of the role of Mesoamerican migrations in the region’s history.

While the exact contours of the connections that bound the people of Greater Nicoya to Mesoamerica are sure to inspire debate for years to come, the evidence unearthed so far suggests they lived in a dynamic landscape of peoples who may have influenced each other much more than any outside cultural force. “In a lot of places that don’t have solid evidence of pre-Hispanic states, you fall into this sort of inferiority complex,” says Roman-Lacayo. “But I’m quite comfortable thinking about a great past of the people in Nicaragua without thousands of people coming down from anywhere else.”