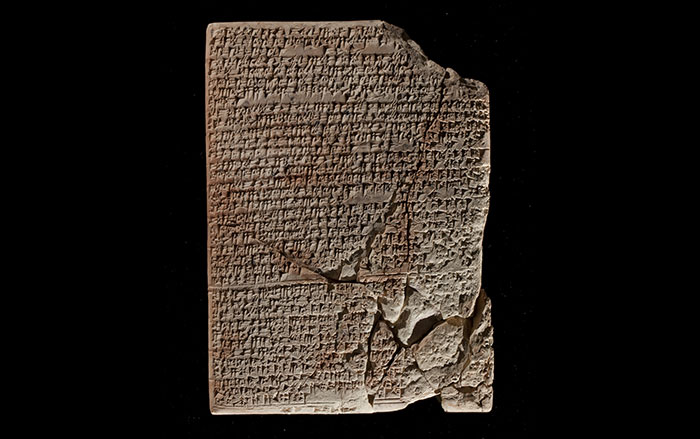

The best known and most influential of the Mesopotamian law codes was that of King Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.). Featuring nearly 300 provisions covering topics ranging from marriage and inheritance to theft and murder, it is the most comprehensive of these codes. While it famously includes retributive, eye-for-an-eye clauses, it also takes on more complex scenarios, imposing harsh punishments for accusation without proof and for errors made by judges.

The code appears written in intentionally archaic cuneiform on a towering seven-and-a-half-foot-tall diorite stela that was recovered from Susa, in present-day Iran, where it was taken after being stolen in the twelfth century B.C. Featuring a relief of Hammurabi receiving divine sanction from the sun-god Shamash in its upper portion, this stela and others like it would have been publicly displayed during Hammurabi’s reign and long after. “The code was certainly set up in in city squares, in temple courtyards, in public places—where it was seen by populations,” says Martha Roth, an Assyriologist at the University of Chicago. It was also used in the training of scribes for at least 1,000 years after its composition, and several manuscripts of it were found in King Ashurbanipal’s (r. 668–627 B.C.) seventh-century B.C. library at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq.

The precise legal function of Hammurabi’s code is unclear, as there are few references to it in legal records from his era. However, says Roth, these records do suggest that “the provisions as outlined in Hammurabi map onto the daily reality in a fairly close way.” The code was also clearly intended to establish Hammurabi as the guarantor of justice for his people. “In order that the mighty not wrong the weak, to provide just ways for the waif and the widow,” reads its epilogue, “I have inscribed my precious pronouncements upon my stela.”

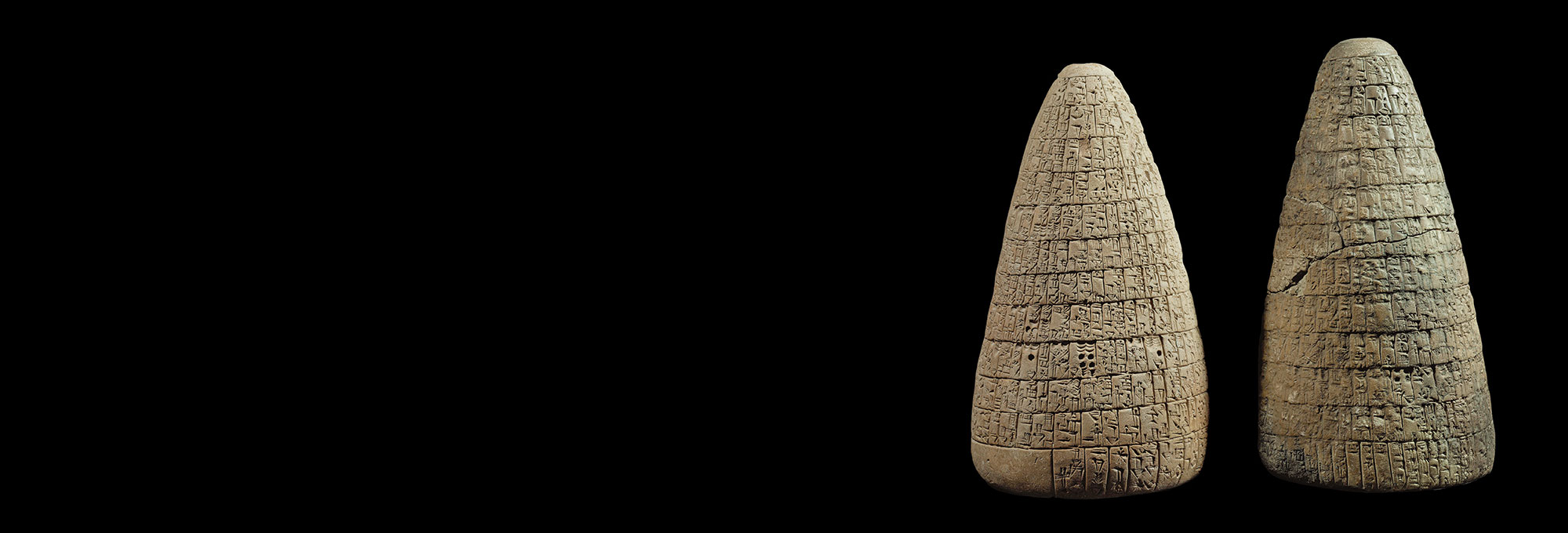

This trope of the king as protector of the downtrodden appears regularly in Mesopotamian inscriptions, but the earliest known example is found on several cone tablets known as the reforms of Urukagina (r. ca. 2350 B.C.), a king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present-day Iraq. According to the inscriptions, the king addressed a number of social inequities, including reducing the power of greedy temple overseers and abusive foremen. “There’s a consciousness about reform in it that is unique until now,” says Roth, “and in history it comes about here for the first time.”