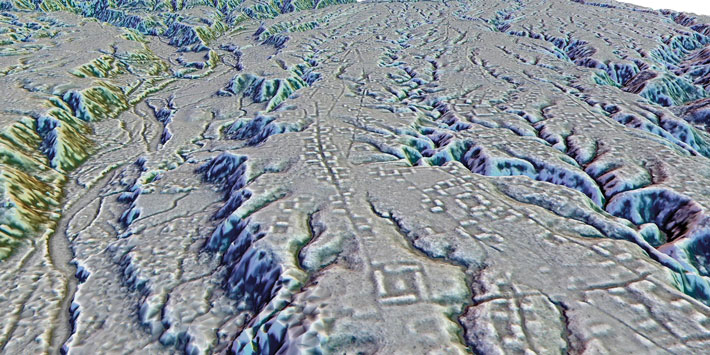

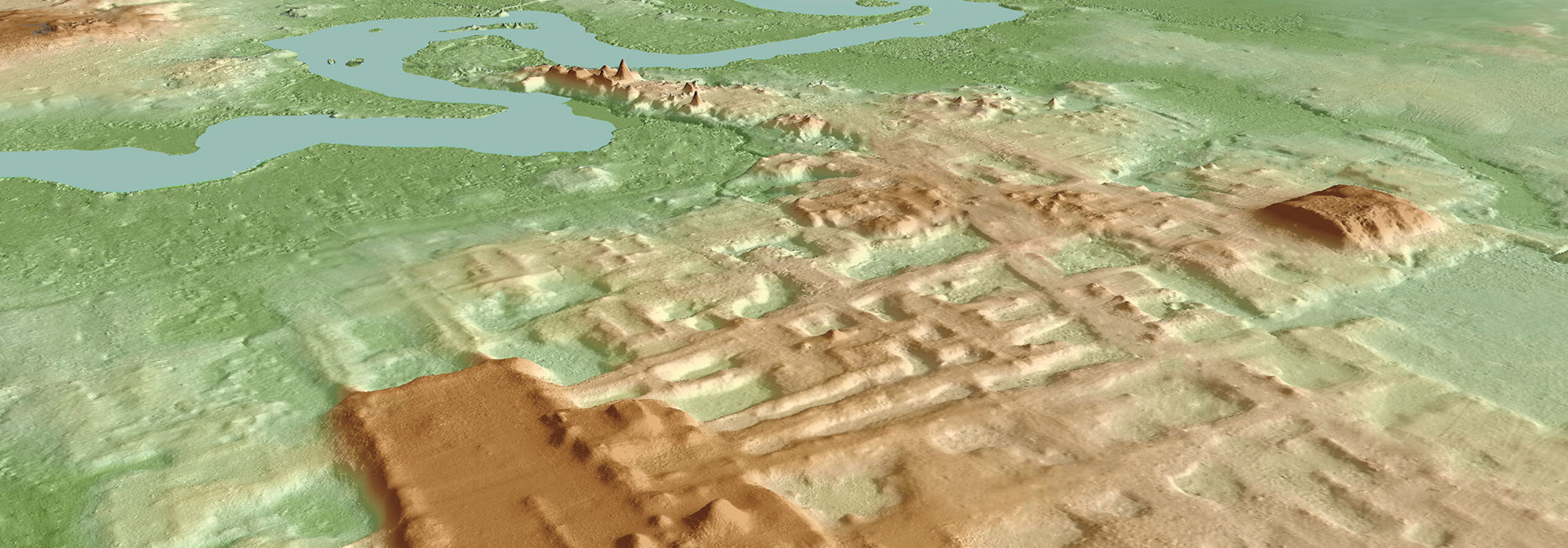

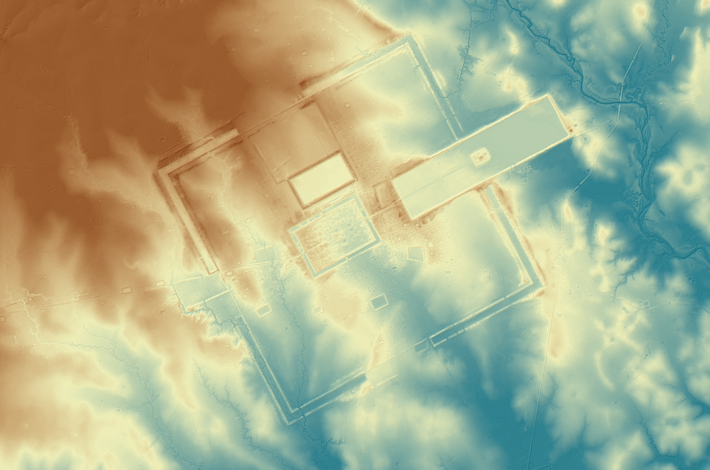

No one disputes that European colonization of the New World devastated native populations. But the timing and scale of that demographic crash are sources of debate among archaeologists and historians. Some believe that Old World diseases, for which Native Americans had no resistance, spread even faster than explorers and colonists, in some regions wiping out peoples before they had any direct contact with Europeans. A team led by Harvard University archaeologist Matthew Liebmann has now tested that hypothesis in northern New Mexico, which the Spanish first reached in 1539. Using lidar images of 18 ruined villages once occupied by the Jemez people, the team estimated the population of these Puebloans through time. They found that it was stable throughout the sixteenth century—well after the first Spaniards arrived in New Mexico. “In this part of the Southwest, massive pandemics did not arrive ahead of or with the initial Spanish occupation,” says Liebmann.

But the study also showed that the founding of a mission church near the Jemez almost a hundred years later had deadly consequences. Liebmann found that the population dropped by almost 90 percent between 1620 and 1640, probably as a result of sustained contact with disease-ridden livestock from the mission. His team also discovered that the number of fires in the area began to increase after this time, probably a consequence of forest regrowth following the drastic depopulation.