Sometimes, shipwrecks appear out of what seems to be merely sand. For more than 350 years, a ship lay unseen just off the Dutch island of Texel in the southeastern part of the North Sea, known as the Wadden Sea. This unique tidal and wetland environment, created by the interaction of salt water and fresh water with the mainland and islands, is one of the most dynamic ecosystems in the world, hosting an extraordinarily diverse biomass. It is home to more than 2,000 species of plants and animals, and is a crucial stopover on the major migratory flyways—between 10 and 12 million birds pass through each year. “This is an area which changes continuously,” says Maarten van Bommel, professor of conservation science and chair of the Restoration and Conservation of Cultural Heritage section at the University of Amsterdam. “Islands here grow and collapse, and the bottom of the sea also changes a great deal.” This can produce some surprises.

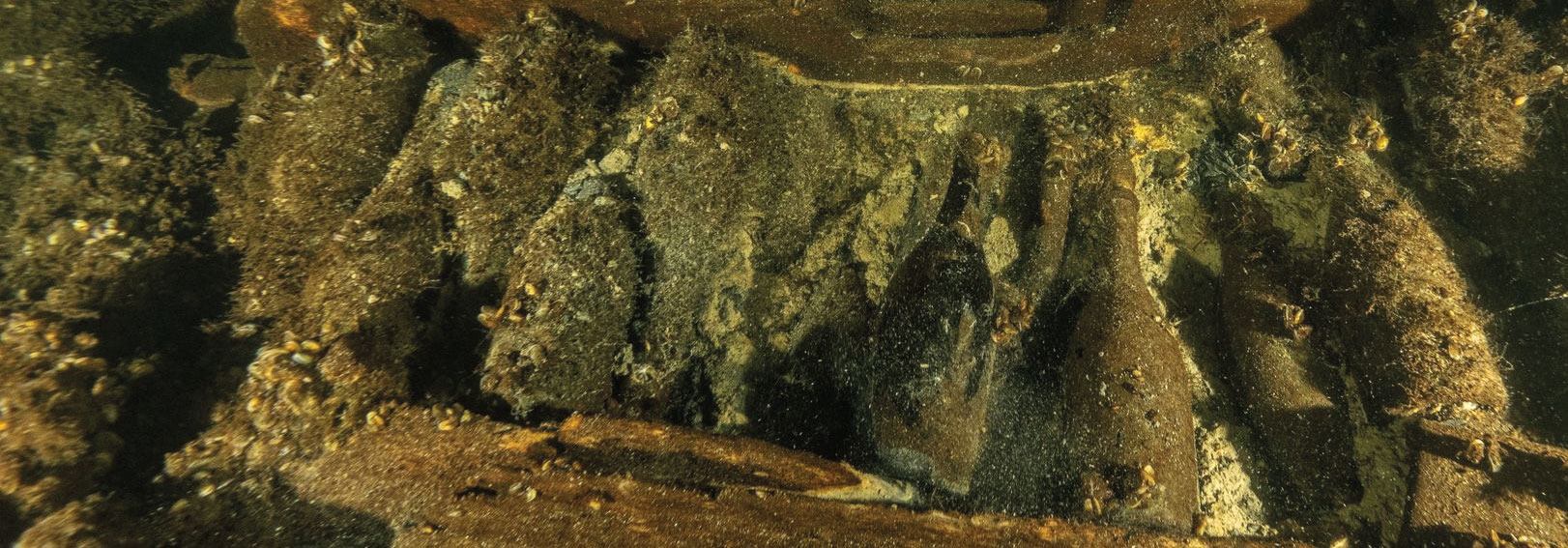

Hidden for centuries at a depth of nearly 30 feet, the so-called Burgzand Noord 17 wreck unexpectedly materialized on the seabed several years ago. A bit of the vessel and some artifacts were first spotted by members of a local amateur diving club in 2009, but it was not until 2014 that more of the ship and its cargo began to emerge. Because of the shifting nature of the seafloor and the need to protect the wreck and its contents from further illegal exploration, the artifacts from the site—which would eventually number more than 1,000—were quickly removed. “Finds appeared that needed to be saved immediately, otherwise they would be gone,” says van Bommel. “There wasn’t the time, as there is on land, to do a proper excavation.”

The particular setting where Burgzand Noord 17 is located has provided both advantages and disadvantages when it comes to the preservation of the ship’s cargo. The wreck sits in an environment that inhibits the oxygen, bacteria, and fungi that typically break down organic material. There, protected from light and currents, protein-based items of animal and insect origin, such as leather and silk, survived for centuries, while those of plant origin, such as book pages, and shirts, collars, and cuffs made of cotton or linen, are missing from the bundles brought up from the wreck, explains van Bommel.

Interestingly, in the Wadden Sea’s diverse environment, shipwrecks just a few miles from Burgzand Noord 17 have contained plant fibers that were preserved. Around 1635, a vessel called the Aanloop Molengat sank on the opposite side of Texel from Burgzand Noord 17. There, both the plant fibers used to bale cattle hides and the poorly tanned hides themselves were recovered. Notwithstanding the vagaries of preservation, Burgzand Noord 17’s stunning collection of silk garments and velvet textiles, leather book covers, and pottery represents the richest cargo of seventeenth-century luxury goods ever found underwater.

On busy days in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, hundreds of ships would anchor on the eastern side of Texel. For large vessels, the island was as close as they could come to the trading capital of Amsterdam because of a sandbank in the city’s harbor called Pampus—a small island there bears the same name today. (This changed in the nineteenth century when massive waterways such as the North Holland Canal and North Sea Canal opened new routes to the city.) Large ships would load and unload their cargo without ever traveling the 55 miles south to Amsterdam’s port, relying on smaller boats and carts to move the goods. Warships such as man-of-war frigates would even drop off their cannons at Texel for servicing in Amsterdam as there was simply no way for large ships to pull into the tricky harbor—unless a spring tide, just after a new or full moon, miraculously eased their way by raising the sea level.

So many ships anchored at Texel that when nasty storms blew in, losses could be catastrophic. On Christmas night in 1593, 24 ships of a fleet of 150 went down. And in early November 1638, 35 ships sank in a single storm. In addition to experiencing frequent storms that doomed ships, Texel and Amsterdam also compared unfavorably to nearby Rotterdam, which offered sailors an easy way to pull in and out of its harbor. It had none of the sailing around Texel and the possibility of having to wait 10 or 12 days for the right burst of wind to propel the ship from what was then known as the South Sea. Even into the nineteenth century, books on navigation warned that although the sea to the east of Texel was mostly calm, it could be choppy when wind came from the west and southwest, with sailing further complicated by the fact that the seafloor near the island was soft mud. They suggested that it was better to anchor in deeper water with firmer ground below, out where the water was 60 to 75 feet deep, to avoid putting down as many as four anchors to no avail.

With such dangers and inconveniences, why did so many ships continue to anchor at Texel each day in order to do business with Amsterdam? Because as the Netherlands raced to the forefront of culture, trade, and science in the seventeenth century, resulting in the period now called the Dutch Golden Age, Amsterdam served as the headquarters for the newly founded Dutch East India Company. Aided by funding from the Bank of Amsterdam and the first stock exchange, investors enabled ships to set out from Texel to explore the world. From Amsterdam—or, rather, from Texel—Dutch East India Company vessels sailed off to trade with areas as varied and far away as Indonesia and Japan, while other Dutch ships went to the Caribbean, Brazil, and North America. They moved everything from spices and silk to sugar and slaves. In this era, ships were mobile, but fragile, packets of wealth.

Shipping had always been dangerous, and the desire to mitigate risk led to the invention of shipping insurance in medieval Italy. Shipping also helped foster early modern café culture and newspapers. Businessmen gathered over coffee and tobacco to wait for news, word of ships’ arrival, and gossip, while newspapers published reports of vessels lost at sea, even in distant locations. As European trade operations spread around the world, information networks metaphorically, and sometimes literally, ran alongside shipping lanes, supporting the new global empires.

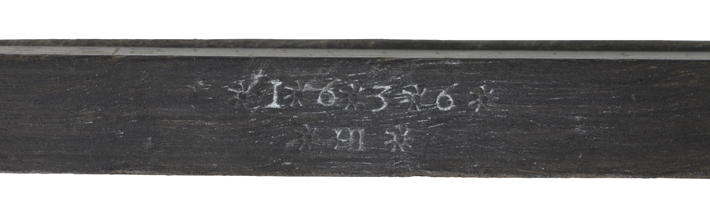

Sometime in the seventeenth century, a ship carrying a great deal of luxury goods was expected somewhere—but it never arrived. The vessel that became the Burgzand Noord 17 wreck sank off the eastern coast of Texel before it could either unload its cargo or sail off with goods obtained from Amsterdam. Exactly what sort of ship Burgzand Noord 17 was, or to whom it belonged, is very much in question. It is known that the vessel sank after 1636, based on the date stamped on a cross-staff found in the wreck. This navigational tool was used to measure angles on land before the practice of using it at sea spread to northern Europe from Spain and Portugal in the mid-sixteenth century. According to van Bommel, it is conceivable that the ship was a straatvaarder, a Dutch merchant ship made to sail beyond the Strait of Gibraltar. Alternatively, he suggests that it could have been an outgoing ship loaded with items collected by many traders. “Amsterdam was a staple market in those days,” he says, “so it is possible that all the goods were brought to the Netherlands by different ships and routes, traded, and collected on this ship. It would then have sailed elsewhere. We are keeping all the options open.”

The items brought to the surface from Burgzand Noord 17 thus far bring the reach of seventeenth-century trade networks to life. Evidence that the ship was associated with the Mediterranean—and beyond—comes from a number of objects possibly linked to the Mughal and Ottoman Empires. For example, more than a dozen fragments of an extremely rare knotted silk and wool carpet are likely from present-day Pakistan, and possibly from the city of Lahore, based on the knotting style and patterns used. According to researchers from the School of Historical Dress in London, the tailoring techniques of two silk caftans from the wreck resemble those made in the Ottoman Empire, some of which are now in the collection of the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. These appear to differ from those made in England for the upper classes in the seventeenth century, but van Bommel says it’s still unclear exactly where they were fashioned. The caftans would have been appropriate as clothing for visitors to the Ottoman court, or they could have been gifts sent to Europe by a member of the court. The garments might also be Eastern European in origin, a theory van Bommel’s team hopes to explore. Containers of mastic, a gum or resin used for incense, paint, and varnish at the time of the wreck, came from the Greek island of Chios, then part of the Ottoman Empire, where it is produced to this day.

The local diving club that discovered the site called it the “boxwood wreck” to distinguish it from others on the eastern side of Texel. The boxwood recovered from the ship is remarkable because it is uncarved. This is the first example of the transport of unworked boxwood yet found, says van Bommel. Boxwood was used in the seventeenth century to create chess pieces, Gothic miniatures, musical instruments, and even tool handles. Lisa Ellis, conservator of sculpture and decorative arts at the Art Gallery of Ontario, a boxwood art expert, notes that it was an expensive raw material because boxwood shrubs grow very slowly, lending the wood unique qualities. According to Ellis, the wood is highly prized for its fine grain. This allows carvings to be executed with a level of detail so refined that they can be hard to see with the naked eye, and are impossible to duplicate in other woods. This, she says, can even allow sculptures made of boxwood to look very much like polished bronze.

The Texel shipwreck’s boxwood cargo may have come from beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, or perhaps from much closer to North Holland. “European boxwood, or Buxus sempervirens, was known to the ancient Romans and was, and is, found around the Mediterranean basin as well as southwest Asia,” says Ellis, but “it was being cultivated as far north as Norway by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.” Boxwood presents a particular problem for archaeologists because dendrochronology is impossible since the wood’s growth rings are not generated in predictable patterns as they are in most other trees. Even if boxwood tree ring dating were methodologically sound, the wood from the wreck is unfailingly attacked by worms almost the moment it comes out of the sand, creating many small holes that could thwart analysis.

Burgzand Noord 17 is notable both for the objects recovered from the wreck and for those that are absent from what might be expected to be part of the luggage of any particular passenger. One missing class of artifacts stands out because the type of woman who would have owned the damask and brocade silk gown that was rescued from the seafloor—a garment suitable as everyday dress for a lady of noble standing—would have traveled with many undershirts. Undershirts are decidedly lacking among the artifacts.

Wealthy Europeans of the time changed their undershirts regularly as a way to stay clean. Ippolito d’Este, a sixteenth-century Roman Catholic cardinal and son of Lucrezia Borgia, is known to have changed his shirt every day, even while traveling. People of lower status would have changed less frequently because of the cost of shirts and laundering, but regularly swapping underclothes was essential at the time because bathing, or even spot-bathing, was not widely practiced. Perhaps the cotton or linen undergarments on the ship simply did not survive being submerged. It is also possible that the silk and damask clothes recovered from the wreck were being transported for sale or delivery.

Conversely, what did survive nearly 400 years in the sand was one pair of silk stockings knitted with incredibly fine-gauge needles and displaying a palmette motif. The popularity of stockings grew in the sixteenth century, but they were very rare and difficult to obtain even among nobility such as the grand ducal Medici family. In 1546, Prince Francesco I de’ Medici’s tutor noted that the boy had only two pairs of badly worn stockings and asked that another pair be sent from Florence. In the mid-sixteenth century, Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga received five pairs of silk stockings, a princely haul for the time, from a man who operated as his buying agent. In the early modern period stockings were not an afterthought, but an essential, precious, and decorative element of elite dress, noted even in descriptions of kings’ clothing. By the seventeenth century, stockings were easier to obtain and even gifts of 14 pairs seemed shabby, while 25 pairs were shipped to Florence in one bundle, according to letters in the Medici Grand Ducal Archive. By the time the Texel ship sank, the palmette motif stockings would have been luxury goods, but not as rare as they would have been in previous generations.

Shortly after it was found, the Burgzand Noord 17 wreck was identified as an English royal ship lost in 1642, a tale the world media ran with. Two historians familiar with the movements of Queen Henrietta Maria of France (1609–1669), the wife of King Charles I of England, suggested that the ship’s rich cargo indicated that it may have been a baggage ship that sank during an unsuccessful mission to secretly sell the crown jewels during the English Civil War. The first garment from the wreck that was revealed to the public, a silk gown, was linked to Jean Kerr, the Countess of Roxburghe and a lady-in-waiting to the queen. A letter written by Queen Henrietta Maria’s sister-in-law about the loss of 12 baggage ships appeared to link the Texel wreck with the English crown. The reality is that many more than 12 ships sank off the coast of the Netherlands in the seventeenth century—there were likely hundreds—and there is no evidence to support the idea that the Burgzand Noord 17 wreck is tied to this historical event, especially given that Texel is more than 100 miles from Hellevoetsluis, where the royal ship is said to have sunk.

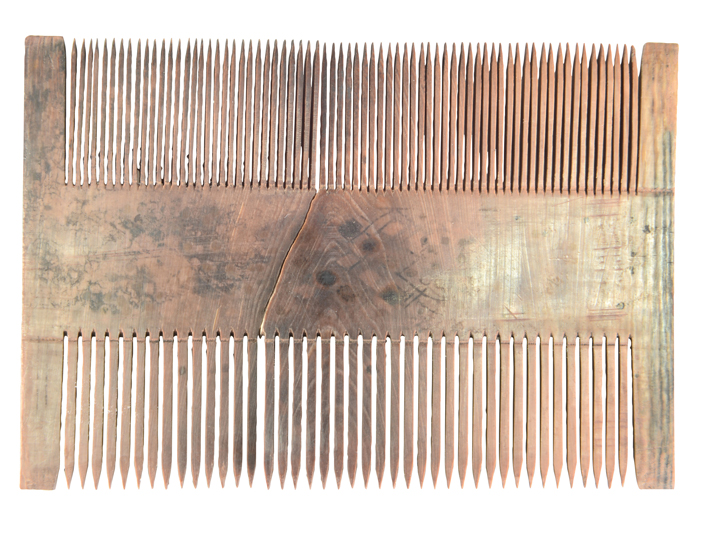

Nevertheless, new information emerges regularly from the teams working on the artifacts. And still other preliminary interpretations are now beginning to be overturned. For example, it wouldn’t be terribly surprising to find a lice comb among the objects from the Texel wreck. Lice, fleas, and bedbugs were common afflictions of the time, most associated with those of lower status, though of course the pests didn’t inquire about rank before crawling on. Considering that lice can spread typhus, the infestations weren’t merely inconvenient, but also dangerous. Yet, upon further investigation, Martin Veen, collection manager of the wreck’s artifacts and administrator of the North Holland archaeology depot, thinks that the item originally identified as a lice comb is in fact a regular seventeenth-century comb. And an object identified initially as a pomander—a metal ball used for holding sweet-smelling herbs and flowers to cover bad odors—is now thought to be a button from one of the garments. Work on the 1,000-plus artifacts already recovered is under way, and a potential trove of untouched objects from the wreck still lie buried and covered by the sea. “The complete project will likely take some years to finish,” says van Bommel. At least for now, the ship sits on the seafloor protected by a net and sand while scholars debate the next step.