As described by the chroniclers of the sixteenth-century Spanish de Soto expedition, the woman known to history as the Lady of Cofitachequi made a dramatic entrance to an audience with Hernando de Soto and his officers somewhere in what is now South Carolina. On May 1, 1540, she was borne to the meeting on a litter decorated with brilliant white cloth. The chroniclers marveled that such a beautiful woman ruled one of the alliances of towns in the American Southeast now known as Mississippian chiefdoms. She evidently exercised canny diplomacy and headed off direct conflict by allowing the Spaniards to spend at least 10 days at Cofitachequi, a large town that lay along a river at the heart of her realm. The Spanish soldiers, some 600 strong, took over half of the settlement, building several temporary structures and robbing the chiefdom’s main temple of a cache of pearls before heading northwest. Another expedition led by the Spaniard Juan Pardo traveled to Cofitachequi between 1566 and 1568, and English colonist Henry Woodward recorded visiting in 1670. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, there are no more references to Cofitachequi in the historical record.

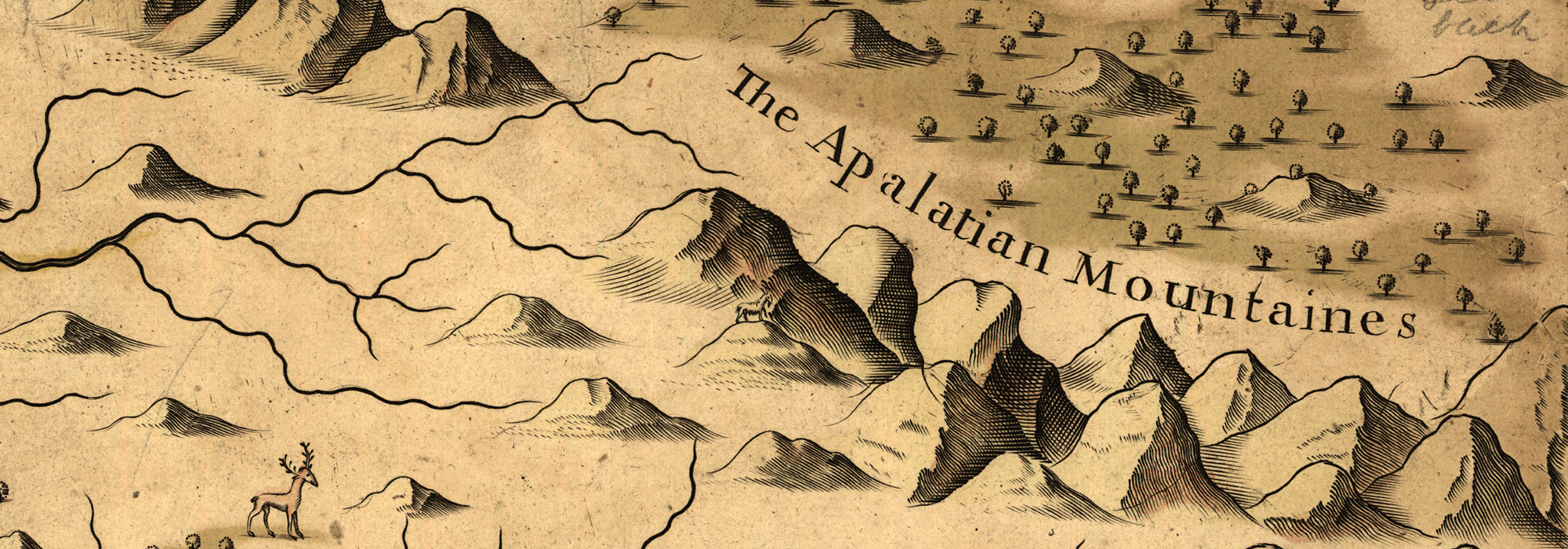

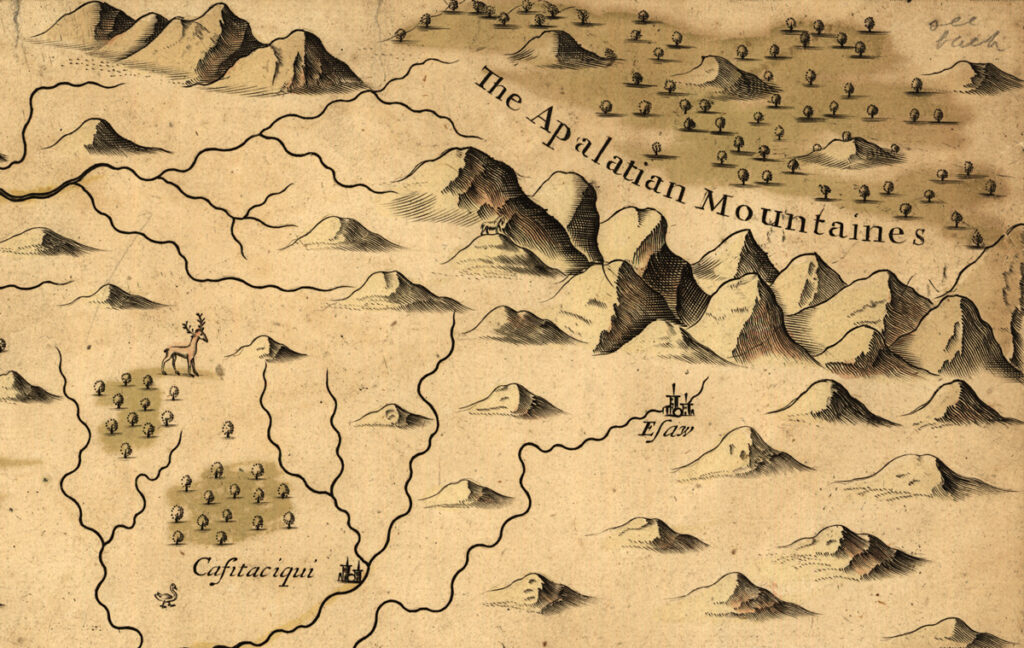

In the mid-twentieth century, scholars using the accounts of the de Soto expedition attempted to identify the location of Cofitachequi. Initially, some believed it was on the banks of the Savannah River, but now most researchers think it was somewhere on the Wateree River in north-central South Carolina. Several mound sites in the river valley might have been the town de Soto knew as Cofitachequi. “It’s not easy to figure out where Cofitachequi was,” says archaeologist Adam King of the University of South Carolina. He points out that finding Spanish artifacts at a site isn’t enough to tie it to de Soto’s descriptions. “European artifacts entered Indigenous trade and kin networks, so finding them at a site doesn’t mean the Spanish were there,” King says. However, identifying traces of Spanish-style structures at a site might help clinch its identification as Cofitachequi. “It was a medieval army traveling with pigs and horses,” says King. “They should have left a substantial footprint—if we can find it.”

The significance of locating Cofitachequi would go beyond simply identifying a stop on de Soto’s journey. “It’s often thought that Mississippian people were powerless and that after de Soto came through, their societies fell apart and they were erased from the landscape,” says King. “But Cofitachequi was a named place that endured for a long time. Finding it would help us tell that story.” Today, several Indigenous groups, including the Muscogee and Catawba Nations, claim a connection with the chiefdom. “Towns like Cofitachequi weren’t really towns so much as social groups,” says King. “They were people with histories, and those histories are connected to people who are still here.”

When de Soto and his men left Cofitachequi, they forced the ruler they were so fascinated with to come with them as a hostage. For several days, the Lady of Cofitachequi traveled with her captors past the limits of her realm. Before reaching the lands of the next powerful chiefdom, though, she outwitted her guards and slipped away, presumably making her way back to Cofitachequi, where her descendants would continue to live for many generations.