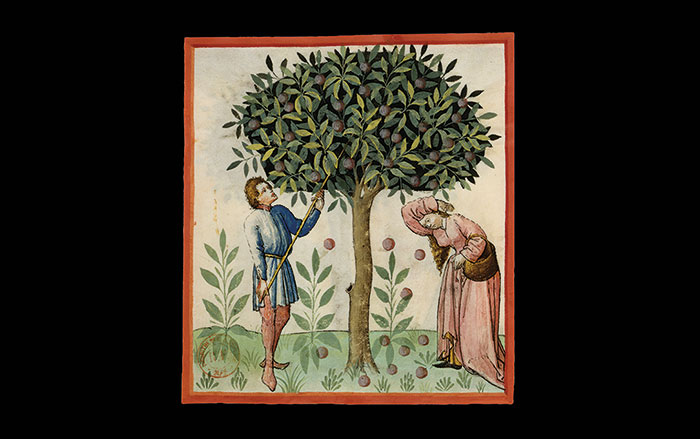

One of the world’s largest Buddhist monuments, which measures some 30,000 square feet, sits in the lush Kedu Valley on the Indonesian island of Java, where the forests teem with mangoes. The Borobudur Temple Compounds are covered with more than 1,000 narrative reliefs illustrating the Buddha’s life along with an abundance of plant life. Among the renderings of foliage decorating panels on the facades are detailed depictions of Mangifera indica, or mango trees, which are native to Southeast Asia and grow near the compound both as a cultivated and wild plant. The Indonesian islands of Java, Sumatra, and Kalimantan are the world’s richest centers of mango diversity.

Considered a symbol of fertility and prosperity, mangoes are the one of the most common plant species shown on the temple compound. Built between A.D. 778 and 824, during the Shailendra Dynasty of the Mataram Kingdom, its panels narrate the story of Buddha by illustrating five sutras, or sacred texts. These include scenes from one of the sutras, the Lalitavistara, which wind across 120 panels made of andesite, a local gray volcanic stone. These scenes include several species of mango trees, as well as the fruits themselves, which are depicted growing in palace gardens, villages, and forests.

Biologist Destario Metusala of Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency identified the various types of mango in the panels by the distinctive shapes of their fruit and leaves. “The reliefs were carved in a very detailed way with a high degree of accuracy,” says Metusala, who believes the ancient Javanese people invested so much time and energy to accurately depict flora such as mangoes because fruit and other materials, such as sandalwood, were the mainstays of the kingdom’s economy and evidence of the region’s wealth. Even today, the people of Java revere the delicious fruit. “Mangoes are still deeply rooted in the traditions of the local people,” says Metusala.