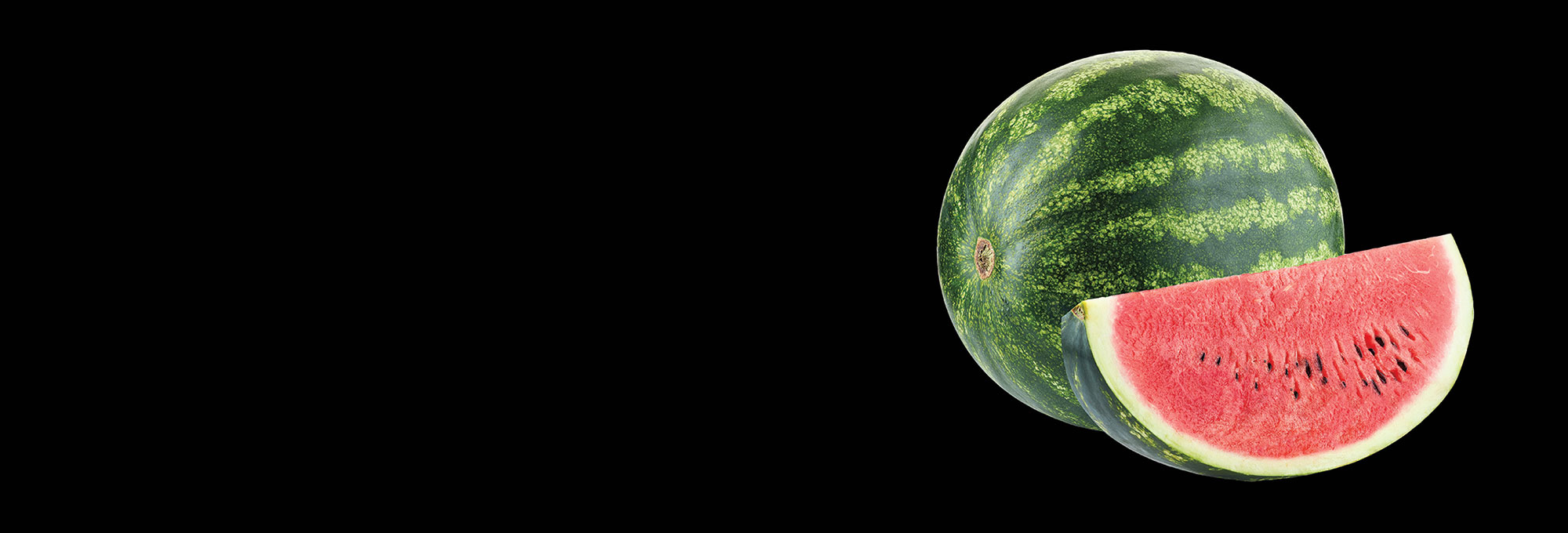

Long before watermelon became a refreshing summer treat, reliefs adorning the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs suggest the fruit was a coveted delicacy. However, exactly when the species of watermelon commonly consumed today, Citrullus lanatus, became the beloved emerald-skinned fruit with white stripes and a sweet red interior is unclear. In fact, its 6,000-year-old predecessor’s pulp wasn’t very tasty and was potentially hazardous. “It actually could have killed you,” says botanist Oscar Alejandro Pérez Escobar of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

To plot the fruit’s evolutionary trajectory, Pérez Escobar’s team sequenced genomes from watermelon seeds dating to between 6,000 and 3,400 years ago excavated from graves in Libya and Sudan. They traced watermelon’s origins to a species closely related to the modern West African Citrullus mucosospermus, which has bitter, greenish-white flesh. This involved identifying the oldest known samples of the genus Citrullus from an archaeological context: 6,000-year-old seeds found in a tomb at the Neolithic settlement of Uan Muhuggiag in Libya. Genomic analysis revealed that the fruit would also have been pale and bitter. Based on damage patterns on teeth from the tomb, the researchers propose that people may have first cultivated Citrullus not for its flesh, but for its seeds, which were likely eaten.