Tortuguero

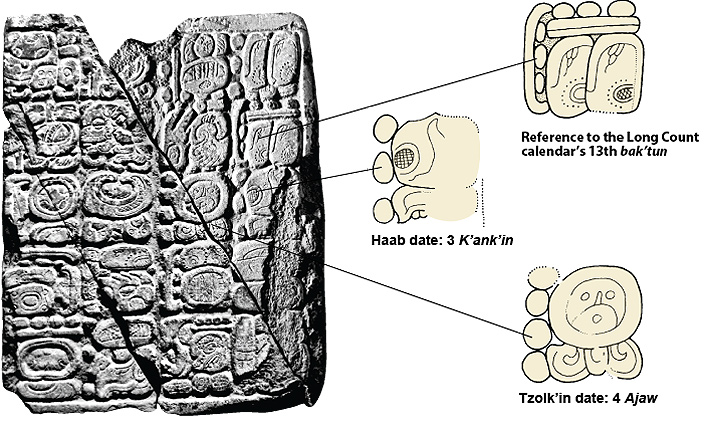

One of the few artifacts that survived being crushed in the gravel factory that now occupies the site of Tortuguero in southern Mexico is a large stone tablet (monument six) that records important events in the life of the ruler Bahlam Ajaw (“Jaguar Lord”), who lived in the early seventh century a.d. The tablet contains one of only two known references to the end of the thirteenth bak’tun (13.0.0.0.0 4 Ajaw 3 K’ank’in), which translates to December 23, 2012. This is the inscribed date that people refer to when they discuss the Maya calendar predicting the end of time.

Chiapa de Corzo

A small fragment of a monument from the site of Chiapa de Corzo in southern Mexico indicates when the earliest known Long Count date was written. Parts of the inscription have been lost, but based on the readable glyphs, Gareth Lowe of Brigham Young University deduced that it probably recorded a date in 36 B.C.

Tonina

The most recent Long Count date comes from a monument at the city of Tonina in southern Mexico. It commemorates the k’atun that ended on 10.4.0.0.0, which took place in A.D. 909. By that time, Tonina’s power and influence were in decline, but the ruling dynasty seems to have managed to hold on to power longer than many of their neighbors.

La Corona

A stone block from a staircase decorated with hieroglyphics at La Corona, an ancient Maya city in northern Guatemala, was carved to commemorate a visit by the king of the region’s most powerful city, Calakmul, sometime after August 5, A.D. 695, when the king had been defeated by an army from the city of Tikal. According to Marcello Canuto, David Stuart, and Tomás Barrientos of the La Corona Project, the king was probably visiting to shore up support among his allies after his defeat. The glyphs refer to the king as “13 k’atun lord”—the end of the thirteenth k’atun had been celebrated a few years earlier. The text goes on to refer to the end of the thirteenth bak’tun, 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ajaw 3 K’ank’in, perhaps as a way to locate the recent historical events within larger cycles of time.

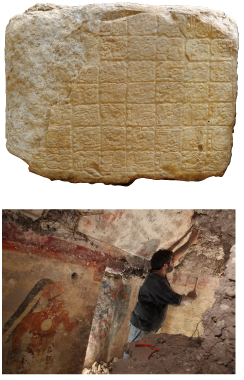

Xultun

Evidence of the way Maya priests calculated calendar dates was discovered earlier this year at the ancient Maya city of Xultun in northern Guatemala’s Petén rain forest. The investigation of a looter’s trench revealed a building that may have been used as a workshop by priests or scribes. In addition to vibrant paintings of a king and other important figures, numbers were painted and scratched into the building’s plaster walls. According to a group of researchers led by William Saturno of Boston University, the numbers were probably tied to calculating the movements of the moon, Venus, and Mars.