John M. Fritz, an archaeologist and consulting scientist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, and architectural historian George Michell, professorial fellow at the University of Melbourne, studied the medieval city of Vijayanagara in southern India, also known as Hampi, for more than 20 years. Recently, the Archaeological Survey of India assumed control of Hampi village within the site, evicting the local community. Fritz and Michell reflect on their long history at Hampi and their ideas for managing “living heritage.”

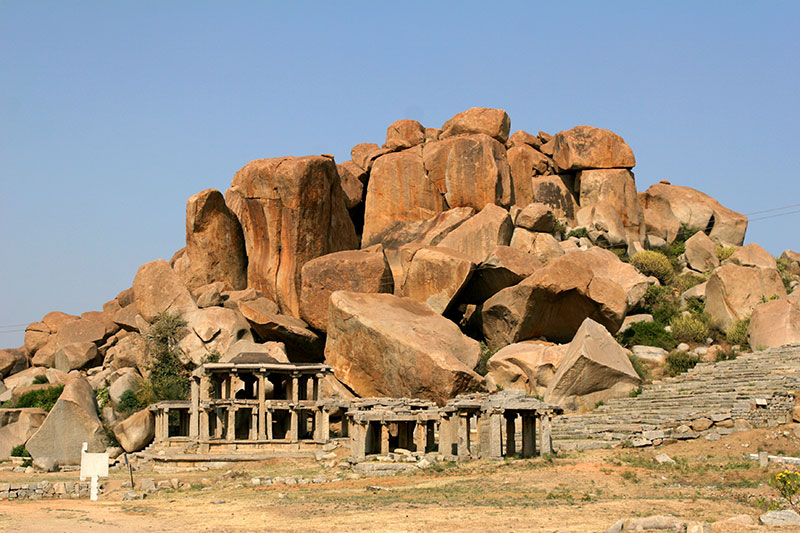

When we first arrived at Hampi, in the state of Karnataka in southern India, in 1980, we encountered a landscape strewn with huge granite boulders and the scattered remnants of a once great city, known during its heyday from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries as Vijayanagara, the City of Victory. The ruins, rarely visited and picturesquely overgrown, consisted of fort walls and gateways, audience halls and pleasure pavilions, and numerous temples and shrines. Though many of the remains were under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and the Karnataka Department of Archaeology and Museums (KDAM), there was a sense then that the place had hardly been touched since January 1565, when the city was sacked by the troops of the neighboring Deccan sultanates and then abandoned. It was like walking into an old engraving. We have, in the 30 years since then, seen many changes come to that landscape, but few as dramatic as what has happened to the site in just the last few years.

Back in 1980, one small part of the site showed signs of life: The village of Hampi bustled in themiddle of what we came to call the Sacred Center of Vijayanagara. A few simple houses clustered around a walled temple consecrated to Virupaksha, a form of the Hindu god Shiva. The medieval temple was, and still is, a place of worship, with resident priests and regular pious visitors. Just in front of the temple’s 160-foot-tall gopuram, or lofty towered gateway, was a broad street that stretched almost half a mile. The street was lined with granite columns that had originally accommodated a market. Portuguese traders who visited in the early sixteenth century wrote that it was stocked with food of all kinds, birds and other animals, and even precious stones, including diamonds. By 1980, there was little besides the columns to recall those times of splendor. But the street was still a commercial center, however modest, known to locals as “Hampi Bazaar.” Between the columns nearest the temple were souvenir stalls; a simple “hotel” offering tea, coffee, and vegetarian meals and snacks;and a bank, presumably with the temple as its principal customer. Each year in March or April, the festival celebrating the marriage of Virupaksha returned to Hampi each winter, with teams of archaeology and architecture students from Indian and foreign universities, to map the medieval city and document its surviving art and architecture. Over those years, we saw the bazaar evolve in ways we never would have expected.

Vijayanagara has always been known to historians of India as the capital of one of the greatest and wealthiest Hindu empires, which, at its height, ruled almost all of southern India. The city’s ruins, the most extensive of any Hindu royal site in southern India, were largely forgotten until the mid-nineteenth century, when they attracted several early photographers. By the turn of the twentieth century, parts of the site had been brought under the control of the newly formed ASI, which, on and off over the years, uncovered and conserved certain monuments. By 1980, the ASI and KDAM were excavating in what we came to call the Royal Center of Vijayanagara, but there was a need for a comprehensive map of the site and an inventory of its visible archaeological remains. Our team, the Vijayanagara Research Project, undertook a study of the religious and royal monuments. In addition, we examined the planning of the city, the extensive military fortifications, a complex hydraulic system, and even traces of the lives of common people.

We became particularly fascinated with the relationship of Vijayanagara’s layout to features in the surrounding landscape. Some of these features had long been identified with episodes in the Ramayana, the Hindu epic, and particularly with tales of the godlike hero Rama and Hanuman, his brave and daring monkeylike confederate. We came to understand that associations between Vijayanagara’s rulers, the gods of myth, and the city’s natural setting were keys to understanding how three successive lines of rulers commanded a kingdom that grew into an empire.

Over the 20 years that we studied the site, we saw Hampi Bazaar return to life. Readily available transportation brought more pilgrims to the Virupaksha Temple, especially at festival time, helping improve the economic situation of the local community. Vijayanagara also gained in reputation, particularly after the 1986 listing of the “Hampi Group of Monuments” on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. By 2002, when we wound up our project, Hampi had become world famous, with thousands of tourists arriving in vehicles ranging from threewheeled auto-rickshaws to airconditioned cars and buses. The local population had also grown dramatically, and the columns of the bazaar hosted a wide variety of shops and services, such as stores selling film, toys, guidebooks, and maps, as well as restaurants with quasi-European menus, travel agencies, Internet cafés, and more. In contrast to the exposed ruins of much of Vijayanagara, Hampi Bazaar was a welcome respite where visitors could find shade and refreshment. Though these modern businesses were occupying the medieval site, they seemed perfectly appropriate—they recovered some of the original function and spirit of the bazaar. We did observe, however, that the temple and KDAM, which had authority over the bazaar, did little to guide this growth or regulate the construction of new guesthouses, some of which soared to three or four stories. Nonetheless, while it was heartening to see the bazaar so animated, we and others were concerned about the integrity of the original structures.

After 2002, we regularly returned to the site and observed a steady acceleration of building activity in the village, accompanied by migration of people from the surrounding countryside looking for work. Many of these migrants were extremely poor, and they converted more and more of the bazaar’s colonnades into simple dwellings and stalls that extended almost the full length of the street. In 2003, the ASI commissioned an Integrated Management Plan for the entire Vijayanagara site. This plan recognized the exceptional value of the Hampi Bazaar, and recommended collaboration with local people in its management and future development. But at no time during this period did the authorities work with the population to restrict inappropriate construction. In our decades working at Hampi, we worked with and got to know many of the local residents. Some of them have told us that they would have welcomed such an initiative, since they had no problem understanding that their welfare depended on the proper management of the site.

The results of this lack of communication became apparent in 2010, when the ASI assumed control of the Virupaksha Temple and Hampi Bazaar. The ASI declared all of the Hampi population to be squatters without any rights, and their stalls, shops, restaurants, and dwellings were deemed illegal encroachments, even those that had been there for generations. The local district commissioner, working with the ASI, issued orders for the bazaar to be cleared and the surrounding houses to be demolished.

Neither the Integrated Management Plan nor the UNESCO listing recommended the removal of the local population from the bazaar. Both recognized that the commercial activity in Hampi Bazaar was in accordance with the site’s medieval tradition. Hampi residents reported to us that no one in the village was consulted on how they might reconcile their personal livelihoods with what was perceived by the ASI as the demands of managing a site of national importance. Despite protests by the villagers, attempts at legal action, and appeals in English- and local Kannada-language newspapers, the decision was ironclad. In July 2011, bulldozers rolled into Hampi, removing the shops, stalls, and hotels, and in some cases damaging the original medieval fabric of the bazaar. More demolition and resulting destruction occurred during summer 2012 and still more is scheduled for the near future. At first, authorities refused to help the displaced villagers, but since then some of them have been offered small residential plots two miles away and portions of another distant area on which to develop commercial sites. However, the community that the bazaar formed and the livelihoods that it supported are now gone.

The residents of Hampi Bazaar, who have been relocated two miles away, return to view the remains of their homes and businesses. A policy of "living heritage" might have allowed the community and medieval site to coexist. While there is an obvious need to ensure the preservation of the medieval remains of the site, we agree with our local contacts that this course of action is callous, not least because the local population was not involved in the decision making process. Unfortunately, this is all too common in India, where there is only a limited range of paradigms for managing heritage sites. Backed by the Departments of Culture and Tourism, the ASI seems familiar with only two approaches. Some sites, like the bazaar prior to 2010, are neglected, unprotected, and open to illegal encroachment and inhabitation. This paradigm, of course, puts sites at risk. Other sites, like the bazaar today, are “protected”—cleared of all encumbrances such as previous inhabitants, set in pleasant garden compounds, and surrounded by walls and gates. Sites subject to this treatment risk becoming the sole province of “five-star” tourism. Though Hampi Bazaar is not the only site to fall victim to one or both of these flawed approaches, it is one of outstanding national importance and international repute. And it aptly demonstrates why such an unyielding policy was not necessary.

Damage to the historical colonnades of the bazaar in recent years was minimal and could easily have been rectified. The essential services the shops offered to pilgrims and tourists were not only welcome, but were also entirely within the spirit of the original bazaar. Indian cultural authorities would only have to look as far as Europe for a different approach: Italy, Spain, Germany, and other countries maintain countless meticulously restored medieval towns with streets and squares surrounded by houses, churches, civic halls, and markets—all crowded with residents and tourists intent on everyday pursuits. Hampi Bazaar could have been such a site, under an alternative paradigm, that of “living heritage,” in which past structures of different types are rehabilitated according to accepted conservation standards, yet adapted for everyday use. Hampi should have seen studies to explore ways to rehab ilitate the bazaar to accommodate modern shops and facilities, while at the same time respecting the historical fabric of the colonnades. After all, this street was originally intended as a setting for bustling activity. To see it empty today is to see it diminished, disconnected from its own past, both ancient and more recent.

In India, as elsewhere, many archaeological sites have seen change and continue to live and breathe. To ignore the full scope of Hampi’s history risks turning a unique relic of medieval commerce and religious faith into a lifeless ruin.

Slideshow: Exploring Hampi

The medieval city of Vijayanagara, also known by its modern name, Hampi, was the sprawling capital of an empire that ruled most of southern India from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. The central part of the site alone spreads across some 6,000 acres, and includes temples, palaces, hilltop shrines, and a staggering variety of art. —Text and Images by Samir S. Patel