In the late 1840s, a young woman, improbably named Cinderella, was enslaved on a tobacco plantation called Belvoir, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Her story, discovered by Chris Haley, research director for the Maryland State Archives’ Legacy of Slavery program and nephew of Roots author Alex Haley, tells of her marriage to Abraham Brogden, a freedman who worked at another plantation nearby. In late December 1848, Abraham learned that Cinderella was to be sold out of the area to pay off a debt. He was unable to purchase his wife himself, so the couple fled to Baltimore. They were caught, however, before the runaway-slave ad even hit the newspaper. Abraham was incarcerated for “enticing a slave to run away,” while Cinderella was returned to her plantation. After serving three years in prison, Abraham was released, but he never reunited with his wife. Cinderella had passed away from unknown causes in the interim years. Local historian Janice Hayes-Williams sees in the story an expression of the aspirations and hopes of the African-American community in the nineteenth century, of boldness and resourcefulness, particularly among women. “There is a significant pattern of enslaved women marrying free black men,” she says. “It was a potential path to freedom.”

The social reality of slavery—including the interactions between free and enslaved African Americans and field and domestic workers, as well as expressions of resistance and paths to freedom—is a matter of great interest to scholars and historians, and also to descendant communities, but it can be difficult to observe in the archaeological record. In many cases, slave cabins were left to rot, or were pulled down in an effort to erase physical reminders of a shameful chapter in American history. But when sites are found archaeologically intact, they can provide details of the lives of enslaved people in the American South, rich with opportunities for connecting with local communities, communities that are often descended directly from the people who worked the old plantations. They have questions, spoken and unspoken, about the trials of their ancestors, and archaeology can provide descendants with that tangible, personal connection to a history both painful and somehow inspirational. This is the story of one such place and its community: Cinderella’s home, Belvoir.

Belvoir has a historical marker on the edge of General’s Highway, northwest of Annapolis, but it says nothing of Cinderella and Abraham. It states that during the Revolutionary War, French commander Comte de Rochambeau and 4,500 troops camped there on the night of September 17, 1781, on the way to Yorktown to fight the war’s final battle. Belvoir was a 700-acre plantation, with a manor house that had been built around 1736 by John Ross. Thirty years later the estate passed to Upton Scott, who expanded the home. The Scotts were part of Maryland’s aristocratic planter class. Francis Scott Key, author of the lyrics of “The Star Spangled Banner,” often came to Belvoir to visit his grandmother, Ann Ross Key. These connections with historical figures have long defined Belvoir’s place in history, and its role in the Revolutionary War was the primary subject of an archaeological survey project in 2014.

The grounds around Belvoir are currently being developed by Rockbridge Academy, a private Christian school. In advance of this, archaeologists with the Maryland Department of Transportation, State Highway Administration (including the author) and Anne Arundel County conducted investigations to find Rochambeau’s encampment and better understand the site’s history. The camp never turned up, but a completely different history emerged, one that, for everyone involved, has indelibly changed Belvoir’s historical narrative.

The only standing structure remaining from the site’s plantation days is the manor house. Immediately south of it is a massive terraced garden, and the landscape suggests that outbuildings and the homes of the plantation’s enslaved population once stood nearby. The archaeological team used remote sensing and metal detecting across the open fields to identify where to dig and determine the layout of the plantation. In an area to the north, downhill from the manor house, the team discovered a piece of white salt-glazed stoneware plate and fragments of bright blue decorated Rhenish pottery from Germany. These sherds clearly indicated the presence of a previously undocumented eighteenth-century household.

As they continued digging, an increase in the age and numbers of the artifacts led the archaeologists to open up larger excavation pits. Ultimately, one of them came down directly on top of a robust stone foundation wall. Following it, the archaeologists delineated a 32-by-32-foot stone building, packed with thousands of artifacts. “When you look around the plantation today, it’s a patchwork of open fields and woods with a brick-and-stone manor house anchored on a hill,” says project archaeologist Aaron Levinthal. “The discovery of these quarters gives another dimension to Belvoir’s past that was invisible until now.”

The archaeologists determined that what they had discovered was not an agricultural outbuilding used for storage or animals. Broken teacups and plates littered a brick floor. It had been a home. Fancy buttons suggest that the residents were well dressed, and artifacts date the building to the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Archaeologists often find it difficult to match a collection of artifacts to a specific group of people without written records. In this case the answer came from a 1798 tax record that listed improvements on the property, including a brick barn, a corn crib, and two “negro quarters.” One was a log house, 30 by 20 feet. The other was stone—32 by 32 feet. This single document made it evident that the building had been slave quarters.

The stone slave quarters at Belvoir proved particularly important in two ways. The structure was rich enough in domestic artifacts to allow the archaeological team to begin to see patterns indicative of daily life, and it was also rich in its direct connections to the area’s descendant community.

During the dig, screeners had to use buckets to collect the hundreds of oyster shells and hand-wrought nails, while archaeologists in the excavation units wrapped fragile animal bones in tinfoil and gingerly picked up fragments of dishes. As they removed the layers of soil section by section, the building’s layout began to emerge and patterns began to form. There were the differences between the rooms to consider, as well as the locations of doorways and windows, and where people cooked and slept.

Food is a significant part of any culture, and it took center stage at the Belvoir quarters. From small root cellars and hearths, the archaeologists collected soil samples. Back in the lab, Kathy Furgerson, the project’s archaeobotanist, filled buckets with the soil and then water. Blackened seeds, fish scales, and charcoal floated to the top and were caught in fine mesh sieves.

After the organic detritus had dried, Furgerson used a microscope to identify the remains of maize (kernels and cobs), wheat, bulrush (cattail) seeds, and even rinds from gourds. The presence of maize hinted at the consumption of hominy and cornmeal. Bulrush reeds may have been used to weave baskets or mats (the flowers can also be ground into a fine flour for baking), while gourds, seldom preserved in archaeological contexts, could have been used as dippers and bowls.

Preliminary analysis of the animal bones from the site shows that the enslaved workers primarily consumed pork, and also ate smaller amounts of beef, mutton, and chicken. However, this supply of domesticated meat provided by the plantation owner was apparently not enough to nourish the enslaved community. To supplement their diets, they snared rabbits, netted fish, and collected turtles from the surrounding woods and streams.

As interesting, and at first puzzling, were the type of buttons recovered in and around the home. Buttons are common at domestic dig sites and may seem to be mundane finds, but they can reveal a lot about the people who wore them. Though now a dingy gunmetal color, the buttons discovered there were once gleaming brass and silver. Items of this quality would have adorned the kinds of waistcoats or overcoats worn by servants who worked closely with the plantation owner. This indicates that the people who lived in the stone house included smartly dressed young men who hand-delivered letters to local businessmen or drove the family into Annapolis for social events.

The wealth of the planter class was reflected not only in stately homes, but also in the way they clothed their slaves. In this case, as shown by the artifacts, the servants also wore beaded jewelry and black pressed-glass brooches, as well as silver cufflinks decorated with a single flower. There was a further distinction, suggested in historical records, between slaves who worked in the fields and those who worked for the plantation family directly. These “house servants,” records imply, may have been more articulate and lighter in skin tone than other slaves. It is likely that Cinderella was among this group. The runaway-slave ad issued after she escaped with Abraham described her as “very pleasant when spoken to, of a light complexion.”

Additional investigation also showed that the architectural footprint of the building was unusual for mid-Atlantic slave quarters. Typically, multifamily buildings were rectangular and designed to function as duplexes, with two front doors, each leading to separate family spaces. In this case, the building was square, with a single front room used as a kitchen, and two back rooms. Why had Scott chosen this floor plan? During the period it would not have been unusual for slave owners to experiment with how best to house, feed, and clothe their workers, and this discussion continued until emancipation, with countless treatises appearing in Southern agricultural publications. In fact, Thomas Jefferson was interested in such deliberations, and once sketched the floor plan for a building that looks almost identical to the Belvoir quarters.

Once it was confirmed that the foundation belonged to slave quarters, the team contacted Hayes-Williams, who knows, perhaps better than anyone, the written and oral histories of black Annapolis. “We have always known these stories through oral history, but archaeology validates what we heard, what we read,” she says. “Archaeology is the visual piece we need to give a greater understanding of what most African Americans think is a lost story.

Some African Americans, however, haven’t lost touch with this past, and have found success tracing their lineages through manumission records, the wills of slave owners, and censuses. Nancy Daniels, for example, is a genealogist. She recalls that when she was younger, her grandmother told her, “Remember who we are, and where we came from. We are from Africa, and we are from Europe.” Daniels found her family, the Burleys, in a record that documented the manumission of Thomas Burley’s family from one Brice J. Worthington in 1854. She also learned that she was descended from Francis Scott Key, and that the Worthington family owned Belvoir during the first half of the nineteenth century. The discovery of the slave quarters at Belvoir was overwhelming, she says. “The stories and old records mentioned a plantation down in the country of Anne Arundel County,” says Daniels. “We never knew where they were talking about. But now we do. It’s Belvoir.”

It was important for this archaeological project to include descendant communities early in the process. Some, including Hayes-Williams, were able to do more than visit the site. They were able to get their hands dirty. As an historian, she is more familiar with archives than with dirt, screens, and bones. At one point in the excavation, Hayes-Williams uncovered a blue shell-edged plate fragment from the fireplace that once warmed a bedroom. She felt an “awakening,” she says. “It was a tragic yet beautiful way to connect, through touching, feeling, what they once held in their hands.”

The landowner, Rockbridge Academy, is committed to preserving the site for future generations, so the fireplaces, foundation, and brick floors were carefully reburied. Before this happened, a closing ceremony was held to remember those who persevered at Belvoir. Visitors walked down to the quarters from the manor house and saw the important architectural elements within the building—the central fireplace where meals were cooked, a worn patch of brick at a threshold where people scuffed their feet as they passed from one room into the next. At the close of the ceremony, the First Christian Community Church of Annapolis choir gathered in the center of the ruin and sang “How Great Thou Art.”

Before the day was over, Daniels shared some news about her personal search for her ancestors. Through genetic testing, she had recently learned that the Burley and Brogden descendants share the same DNA, which means she is also related to Abraham, Cinderella’s husband. Through intermarriage and inheritance, enslaved Africans were passed between colonial planter families, resulting in close kinships among them. Today, the story of African America survives in this lineage, on faded parchment, and in the broken bits of everyday life. Daniels urged her community to continue the search for their ancestors. “They struggled and fought to live for their family, ” she said. “It is important you go out and find them—they are there, and they are waiting for their stories to be told.”

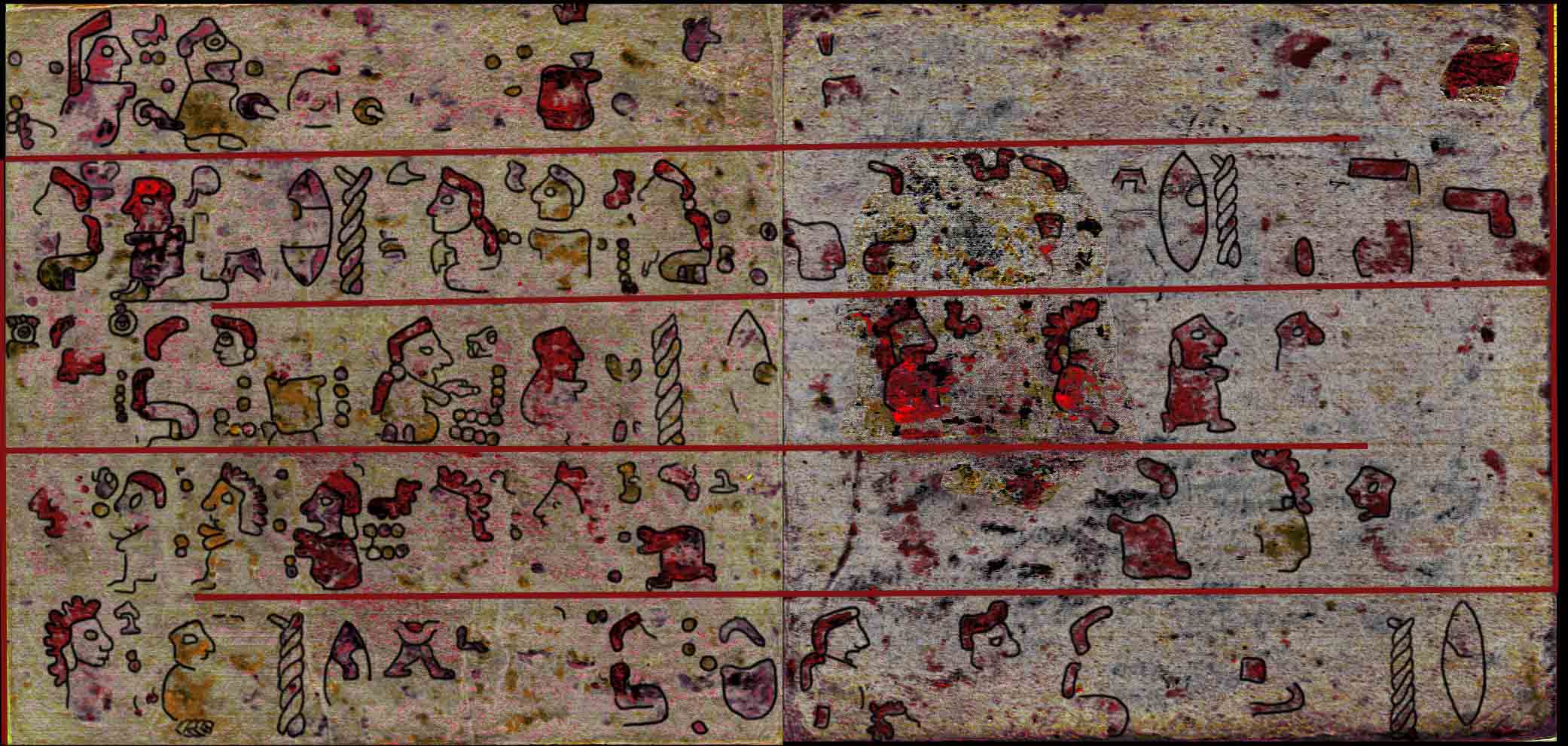

Animation: Belvoir Slave Quarters

This digital animation gives viewers a chance to virtually walk through the Belvoir slave quarters. It was created by a team of archaeologists and 3D reconstruction artists using architectural elements and artifacts discovered during excavations. The building was occupied between the 1780s and 1860s, so the team needed to decide which era they wanted to represent in the animation. Since there are, today, known descendants of the enslaved community who lived there between 1816 and 1850, the team chose to furnish the quarters with artifacts from that specific time period. Furthermore, the mugs and jars sitting on shelves, as well as the stoneware butter churn, for example, are based on ceramic sherds that were unearthed at the site. Even the ducks, gourd dippers, and corn hanging in the kitchen were inspired by archaeological finds.

Drone photography and LiDAR scanning of the site allowed the team to capture the exact measurements of the stone foundation, brick walls, and fireplaces of the building’s kitchen and two bedrooms. It was even possible to add small cellars and the brick floor patterns with exact precision. When it came time to make decisions about the number of window panes, the spacing of joists, and color of paint trim, an architectural historian provided direction based on similar buildings from the late eighteenth century.