In 1872, some 150 members of the Modoc tribe took refuge in arid and unforgiving terrain just south of the Oregon-California border. Today, Lava Beds National Monument encloses 73 square miles of this harsh landscape on the southern edge of Tule Lake. Eruptions as recent as 800 years ago have left raw expanses of lava, tuff, and obsidian pocked by caves and laced with the largest known concentration of lava tubes in North America. Here, amid a maze of volcanic walls, boulders, fissures, and holes, 50 to 60 Modoc warriors held off a much larger force of U.S. Army soldiers for half a year.

The Modoc War is far less well known than other major Indian wars of the late nineteenth century, such as the Great Sioux War of 1876, which is famous for the Battle of the Little Bighorn. “The Modoc War remains an untold piece of American history,” says National Park Service archaeologist David Curtis. “It was very short, but the archaeological footprint that was left behind is enormous. It rivals Civil War battlefields.” For two years, Curtis has led a team of archaeologists studying this vast site. They are building on a comprehensive survey conducted by archaeologists Eric Gleason and Jackie Cheung for the National Park Service in the wake of a 2008 fire that burned off much of the vegetation that had grown in the 136 years since the Modoc War. That fire brought the site closer to its nineteenth-century appearance and exposed numerous features and artifacts dating to the war. Gleason and Cheung’s work was aided by the fact that newspapers and magazines of the time sent numerous correspondents to California to cover the war. Comparing these accounts and contemporary photographs with archaeological findings has added new layers of understanding to this often-overlooked episode in the history of the American West.

People have inhabited the Tule Lake Basin for at least 11,500 years. By the nineteenth century, bands of Modoc lived in seasonal villages along the banks of the Lost River, the lake’s source, which empties into its northwest corner. Nicknamed the Everglades of the West, the lake once covered 100,000 acres and provided local tribes with abundant fish, game, and edible plants. The Modoc moved between permanent dugout homes in the winter and temporary structures built near seasonal food sources in the summer. Tule reeds supplied them with sustenance as well as sleeping mats, moccasins, baby cradles, and baskets woven from its fibrous stalks.

Settlers started to arrive in large numbers in 1846, when pioneers blazed a side branch of the Oregon Trail through the area. Tensions escalated into raids and ambushes by both sides, and in 1864 the federal government pressured the Modoc to give up their traditional lands and settle on a nearby reservation. But when the government didn’t provide enough rations, tribal members began to return to their homelands, some of which were now occupied by settlers.

In November 1872, U.S. Army troops arrived at Lost River to convince a band of Modoc led by a chief known as Captain Jack to return to the reservation. Captain Jack and his group refused the military’s order, and gunfire erupted, with casualties on both sides. Captain Jack’s band fled by canoe, and at the south end of the lake they were joined by other groups of Modoc, including one band that had killed 14 settlers as they traveled down the lake’s eastern shore. Together, the Modoc bands dug in on top of a 30-foot-high plateau of lava surrounded by deep fissures. Bordered by the lake to the north and more lava fields to the south, the place was known to the tribe as the “land of burned-out fires.” As a result of the events that followed, it would be known to history as Captain Jack’s Stronghold.

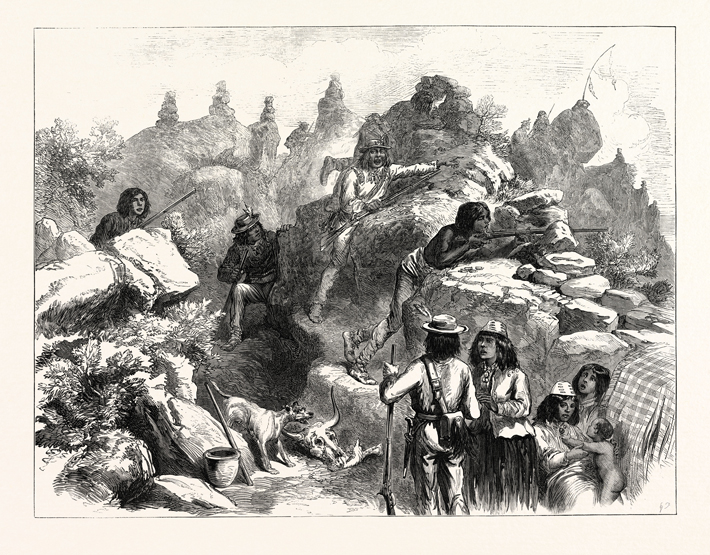

The Army set up camps in open areas to the east and west in an attempt to surround the tribe. On the foggy early morning of January 17, 1873, more than 300 soldiers and volunteers from Oregon and California attacked from both sides. Even though their forces outnumbered the Modoc six to one, the assault quickly turned into a disaster for the Army. Lava cracks in the stronghold made ideal rifle trenches. Concealed Modoc snipers picked off Army soldiers as they crossed open fields of sagebrush, and dense fog made it impossible for the soldiers to use their mountain howitzers with any accuracy.

When it became clear that the plan to encircle the Modoc wasn’t working, the Army troops withdrew, counting 12 killed and 25 wounded. By contrast, only a few Modoc were wounded, and after the Army’s retreat, the warriors were able to collect Army rifles and ammunition from the battlefield. Both sides dug in for what was to become a six-month siege.

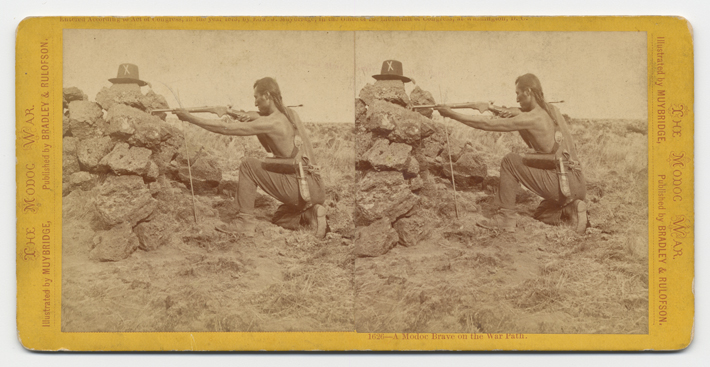

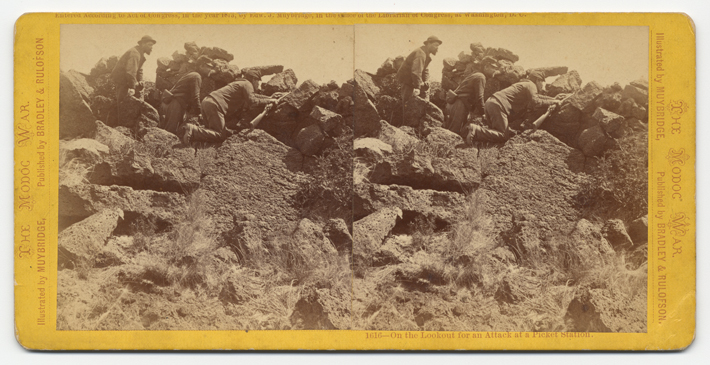

Today, a visitor to the battlefield can still make out cairns, walls, and other structures built of basalt stones by both the Modoc and the U.S. Army. In their survey, Gleason and Cheung recorded 756 fortification features here in all, including at least 569 rifle pits, or small barricades built for cover during battle. It wasn’t always obvious to the pair whether a feature was natural or constructed, especially since basalt tends to fracture naturally into flat-sided building blocks. But it was usually clear which side built a feature based on its shape or orientation. Gleason notes that some fortifications were obvious Army picket posts, waist-high circular walls of stones that sheltered three or four men on guard duty. Low C-shaped walls protected individual riflemen lying on the ground.

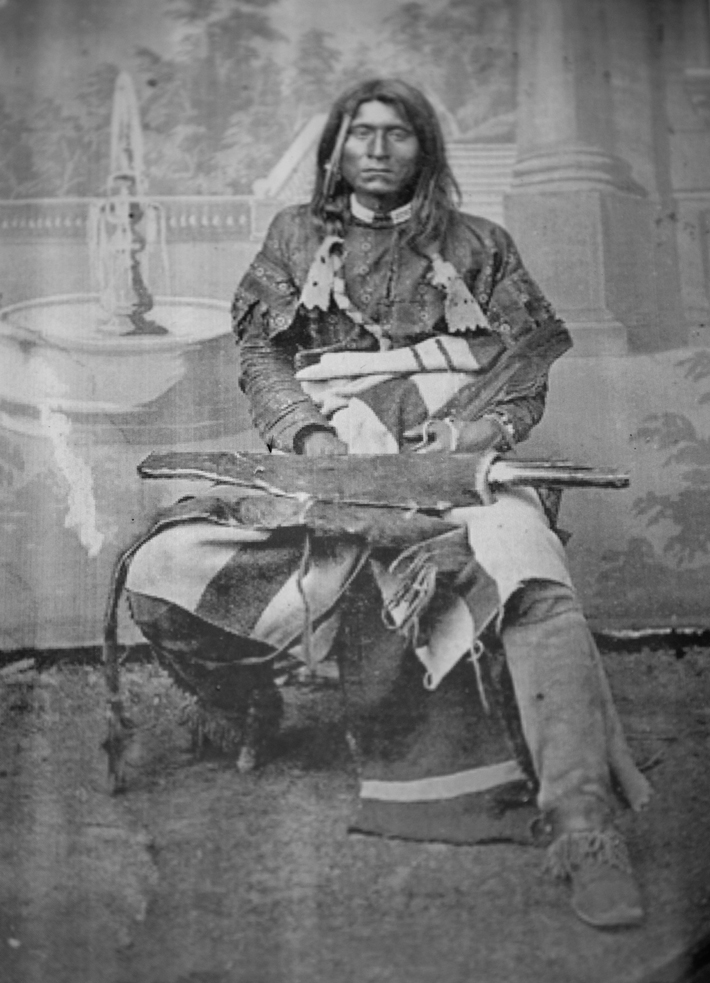

The survey showed that the action happened over a much larger area than was previous thought, expanding the stronghold from 183 acres to 445. Gleason and Cheung were astounded by how intact the site is. “You can still match individual rocks in historic photos,” says Gleason. This is in spite of the fact that souvenir-seeking tourists have been traveling to the battlefield since 1873. At least initially, these visitors were drawn in part by the extensive international media coverage the war received as it unfolded. Correspondents from Harper’s Weekly and The Illustrated London News filed stories from the field, and a reporter from the New York Herald even secured an interview with Captain Jack. The photographers Eadweard Muybridge, who is famous for his motion studies of animals and people, and Louis Heller took dozens of stereoscopic images of the lava fields and participants on both sides. The coverage swayed public opinion to the side of the besieged tribe—at least at first. It also provided a rich contemporary record that historians and archaeologists are still tapping.

These accounts described the Modoc as taking full advantage of the lava plateau’s natural defenses. One Army captain involved in the fighting said, “I have never before encountered an enemy, civilized or savage, occupying a position of such great natural strength as the Modoc stronghold, nor have I ever seen troops engage a better armed or more skillful foe.” It didn’t help that the attacking troops were “a hodgepodge from all over after the Civil War,” says Curtis. “They were undersupplied, morale was low, and a lot of them were volunteers.” In contrast, the Modoc considered the entire landscape sacred. “You can only imagine their determination,” he adds.

Over the three months after the initial Army assault, the Modoc settled in and tended to their defenses. Documenting these natural and constructed fortifications helped illuminate the Modoc battle strategy. “The original idea was that the Modoc picked a pretty good spot and were pretty good fighters,” says Gleason. “Now we know they were improving it, building fortifications in strategic locations, even burning brush for visibility.”

The Modoc also built corrals for 100 or so wild cattle that had roamed the lava beds and constructed camps consisting of small lodges out of willow poles and mats woven from tule reeds. Gleason and Cheung were able to pinpoint and survey seven of these Modoc camps, showing for the first time how the tribe remained divided into small bands just as they had been before the fighting. Despite more than a century of souvenir-hunting, artifacts such as cow bones, buttons, beads, and rifle cartridges remain at the camps. Using historical photographs, Gleason and Cheung identified one of the camps as belonging to the Hot Creek band. This site has special significance to Cheewa James, a Modoc historian and author who has worked at the monument. Shacknasty Jim, the Hot Creek leader, was James’ great-grandfather. Shacknasty Jim’s son Clark, her grandfather, was born there during the siege. “When I used to lead tours, I’d look in the caves and wonder if that’s where they lived, where my grandfather had been born, but we had no way of knowing,” she says. James’ first visit to the campsite after archaeologists identified it as the place of her grandfather’s birth was a moving experience. “My hair must have been at least six inches off my head,” she says. “It was just astounding, seeing where they lived and ate, where my grandfather was actually born. It’s astonishing to think that life continued right there. That’s where he survived.”

Some Modoc chiefs and their families sheltered in caves formed by collapsed lava tubes. Devery Saluskin, a member of the Modoc tribe who worked as an archaeological technician during the 2010 field survey, also has family ties to the site. He was able to visit the cave where his great-great-great-grandfather Peter Schonchin lived during the siege. “Seeing where he slept as a 14-year-old boy, it’s not just some far-off history,” Saluskin says. “It really brought me closer to my ancestors.”

At 43 by 23 feet, Captain Jack’s cave was the largest. Here was where the Modoc leaders sat and argued through the winter about what course to take. The tribe wanted six square miles of their ancestral homeland to settle on permanently, while the U.S. government demanded they hand over the warriors who had killed the settlers.

The government eventually formed a peace commission headed by Brigadier General Edward Canby and set a meeting for April 11. In the stronghold, Jack argued for reaching a peaceful settlement. Other Modoc chiefs wanted to keep fighting. They pointed out how the whites had killed Modoc people, including some of their own family members, under flags of truce more than once. They may also have thought that if they could kill the Army leaders the troops would be demoralized and end the siege. Jack was mocked and overruled.

The meeting of the peace commission and the Modoc chiefs fell on Good Friday. Jack’s cousin, a bilingual Modoc woman named Winema (also known as Toby Riddle) served as interpreter along with her white husband. She had warned Canby of rumors of an ambush, but he insisted on receiving the chiefs at the Army’s western camp. The two sides had talked for less than an hour when the Modoc pulled out pistols, killing Canby and another negotiator and severely wounding Alfred Meacham, superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon. Winema dragged Meacham to safety, and the Modoc fled back to the stronghold. Canby was the only full general killed during the Indian wars and the ambush made international news. It also turned public opinion against the tribe. The Army brought in hundreds more soldiers to remove the Modoc once and for all.

Gleason and Cheung have identified three Army camps, cataloging artifacts such as glass bottles, tin cans for food and tobacco, horseshoes, nails, and clothing fragments. Rifle cartridges and bullets were among the most common items in camps and on the battlefield. Identifying them by make and model enabled the researchers to recreate skirmish lines and sniper positions based on where different types of ammunition were found, since the Army used breech-loading rifles and pistols, while the Modoc mainly used older muzzle-loading rifles.

Pieces of mortar rounds, howitzer shells, and friction primers—a trigger mechanism for cannons—showed where the Army had set up emplacements for mortars and mountain howitzers, light and portable artillery pieces that had been used extensively in the Civil War. By examining historic records of the fighting, Gleason says it was possible to narrow down the provenance of some artifacts to an astonishing degree. “It’s not very often in my career I’ve been able to pick up an artifact and know the day it was dropped and probably the person who dropped it,” he says.

For Saluskin, recovering artifacts such as the shell fragments initially provoked another kind of response. “That’s not just some artifact,” he remembers thinking the first time he saw one in the field. “That shell was sent to kill my ancestors.” It took some time for him to become accustomed to nonmembers of the tribe handling these kinds of objects, he says, even for scientific purposes. But the archaeological work offered him new insight into an event that was critical to the history of his people. “I got to know that place intimately, wandering all over, being able to let my DNA experience every crack and crevice and lava mound and rock wall.”

On April 17, 1873, the Army attacked Captain Jack’s Stronghold again. As before, troops advanced from the east and west simultaneously, with the goal of encircling the Modoc and cutting them off from the lake. This time the fighting force was not made up of volunteers, but solely of professional soldiers—close to 700—accompanied by scouts from the Warm Springs tribe of northern Oregon.

“After the first battle, the soldiers were really leery of the Modoc and their ability to move and shoot,” Gleason says. According to newspaper reports, Army veterans of the first battle knew enough to advance at night, blackening their faces and guns and covering their heads with dark cloth. Mortar fire covered their movements. But their advance was initially stymied by the additional fortifications built by the Modoc and the fact that there was no brush to use for cover.

After fighting their way into the stronghold, the soldiers found it deserted except for a few Modoc who were too sick or injured to travel. The defenders had slipped out under cover of darkness and headed south. The battle left six soldiers dead and 17 wounded, with only two to four Modoc casualties.

Two weeks later, a band of Modoc warriors ambushed an Army scouting patrol made up of 60 men at Hardin Butte, four miles south of the stronghold. The attack left 22 soldiers dead, including all five officers. A Modoc chief nicknamed Scarfaced Charlie is said to have let the rest of the soldiers go, shouting, “We don’t want to kill you all in one day.” But the victory masked the toll the retreat from the stronghold had taken on the Modoc. Famished and weary, the Hot Creek band surrendered on May 22, followed by Captain Jack’s group 10 days later.

A military court sentenced Jack, Schonchin John (Peter’s father), and two other Modoc chiefs to death. Two more chiefs were sent to Alcatraz for life. After the hanging, the prisoners’ heads were sent to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., though they have since been repatriated to the men’s descendants. The remaining prisoners were transported to a reservation in Oklahoma, where nearly half died from disease and malnutrition over the next decade.

The Modoc War was the only major Indian war in California, and relative to the number of combatants, it was one of the most expensive in U.S. history. To defeat some 60 native warriors, the government spent an estimated $400,000–$500,000, the equivalent of $8.4 million–$10.5 million today, and counted more than 100 casualties. In comparison, the six square miles the Modoc had requested to settle on would have cost $20,000.

Today there are about 300 Modoc in Oklahoma, and about the same number belong to the Klamath Tribes of southern Oregon, which include the Klamath and Yahooskin peoples. In 2017, the Modoc tribe of Oklahoma made a return of sorts to their ancestral lands by purchasing 800 acres to the north and west of the monument. It is important, says Saluskin, for the tribes to be as involved in the archaeology and administration of the site as possible. “It’s not just a snapshot of 1872,” he says. “It’s a sacred place, and it’s a sad place.” Near the end of a trail that now wends through Captain Jack’s Stronghold stands a 10-foot pole that was wedged upright in the rock after the 2008 fire. It is covered with bandannas, baseball hats, colored cloths, and beaded jewelry, items left by Modoc to honor their ancestors’ act of defiance.