The Roman orator and rhetorician Eumenius delivered a speech to the Roman governor of Gallia Lugdunensis in A.D. 298 advocating for the restoration of the famous schools called the Maeniana in the city of Augustodunum, at the center of the province. At the time of Eumenius’ speech, the once-thriving city had fallen on hard times. In A.D. 269, its residents had taken sides against Victorinus, the emperor of the ill-fated breakaway state now known as the Gallic Empire (ca. 269–271 A.D.), and the city was besieged for seven months. Access to the high level of culture and education that had been central to Augustodunum’s identity fell victim to a combination of circumstances, perhaps including damage to the Maeniana, funding diverted to the conflict, or a diminished student population.

Augustodunum (modern Autun) had been founded around 13 B.C. by the emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14) as a new capital for the Aedui, a Celtic tribe that was—mostly—allied with the Romans. By 121 B.C., the tribe had been awarded the title of “brothers and kinsmen of Rome.” The Aedui largely supported Julius Caesar in his campaigns in Gaul, with the exception of a brief defection in 52 B.C. when they joined an unsuccessful rebellion led by Vercingetorix, the doomed chief of the Arverni tribe. The capital of the Aedui had been located at the settlement of Bibracte, but when the tribe became a civitas foederata, or allied community, of Rome, it was moved 15 miles east to its new location. It was given a name that combined its Roman and Gallic identities: Augusto- for Augustus, and -dunum, the Celtic word for “hill,” “fort,” or “walled town.”

From the start, Augustodunum was a city with a status and appearance befitting the prestige of the Aedui and their Roman governors. The provincial capital city of Lugdunum (modern Lyon), a little over 100 miles south, was its only superior in architectural splendor, economic prominence, and population in the region. “Augustodunum was one of the most important cities in Gaul,” says archaeologist Carole Fossurier of France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP). For most of the nearly three centuries preceding Eumenius’ oration, it was a thriving university town and one of the most Romanized in Gaul. It was encircled by a stout 4.5-mile city wall that enclosed an area of about 500 acres, with straight Roman streets laid out on a grid plan. It was also home to Gaul’s largest theater, an amphitheater, shops, manufacturing quarters, public baths, luxuriously decorated residences, a forum, numerous temples, and, eventually, places for Christian worship. The city was traversed by a major Roman road built by Augustus’ son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa for military use and to encourage trade by connecting the province to the English Channel. Under the emperor Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54), who was born in Lugdunum, the Aedui became the first Gallic tribe whose members were allowed to serve as senators in Rome. In Augustodunum, writes the first- and second-century A.D. Roman historian Tacitus, “the noblest youth of Gaul devoted themselves to a liberal education.”

After the siege by Victorinus that damaged the city, the emperor Constantius I (r. A.D. 293–306) became Augustodunum’s benefactor. He promised to restore the city to its former status and appearance, an effort that was continued by his son, the emperor Constantine I (r. A.D. 306–337). “Augustodunum wanted to be a provincial capital,” says University of Kent archaeologist Luke Lavan, “and to become one, it competed with other provincial centers in Gaul for the emperor’s patronage.”

Christianity was well established in Augustodunum by the early fourth century A.D. In A.D. 313, its first recorded bishop, Reticius, was honored with an invitation to Rome to help resolve the schism in the church caused by the Donatists, a North African sect of Christians. One of Gaul’s oldest Christian inscriptions was found in a city cemetery in 1839. According to INRAP archaeologist Michel Kasprzyk, it dates to the late third or early fourth century a.d. The document’s Greek text, he explains, includes the name of a Christian man, Pektorios, and an acrostic of the Greek word ichthys, or fish, an early Christian symbol of Christ.

Another rare text included in a set of panegyrics called the Laudes Domini dates from A.D. 290 to the 310s and describes the city’s appearance in antiquity. This collection of speeches was made by delegates from Augustodunum to the imperial court at Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier). From about A.D. 250 to the middle of the next century, Trier was one of the largest cities in the empire and served as a residence for the Roman emperor. The texts mention many monuments in Augustodunum, some rebuilt after the crisis of the late third century A.D., including baths, aqueducts, houses, and the schools of the Maeniana. One describes a visit to Augustodunum by Constantine at the end of A.D. 310 during which he was shown “all the statues of their gods,” a clear indication, says Kasprzyk, that the city was both pagan and Christian at the time.

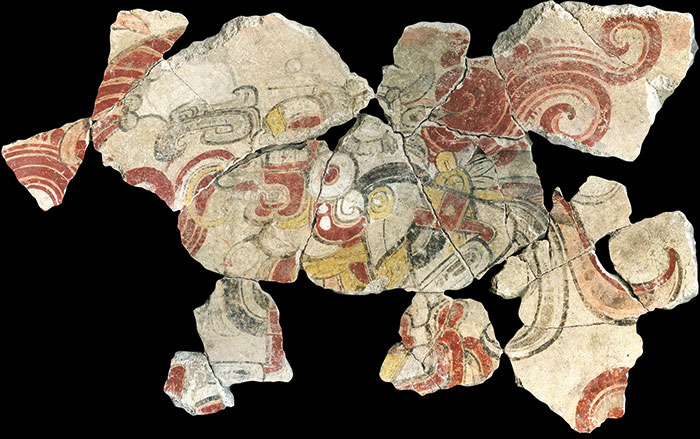

Archaeologists have explored Autun periodically for decades. Still, very little of Augustodunum—perhaps only 3 to 4 percent—has been investigated, and only through small surveys, limited excavations, and sometimes accidental discoveries. Researchers have unearthed the remnants of ancient structures, including possibly the Maeniana, as well as aqueducts, marble sculptures, and finely crafted mosaics that once covered the floors of the city’s wealthiest residents’ homes. Some of these mosaics depict scenes from Greek mythology, such as the story of the hero Bellerophon, who killed the mythical beast the Chimera. Others include portraits and sayings of Greek philosophers. These are testaments to the influence of Greco-Roman high culture in Augustodunum and to its well-educated citizenry. Part of Augustodunum’s fourth-century A.D. church was excavated in the 1970s, and several acres of one its largest ancient cemeteries were dug in 2004.

In 2020, INRAP archaeologists Fossurier and Nicolas Tisserand led an excavation, which they have since completed, in an area of Autun known as Saint-Pierre-l’Estrier. There they uncovered new evidence of the lives and deaths of Augustodunum’s residents. On the site where a house was being built, they made a spectacular discovery—a necropolis containing more than 250 burials dating to the third through fifth centuries a.d. The graves represent a variety of religions and economic statuses and contain some of the most valuable artifacts from the Roman world.

Among the types of burial the team discovered were several mausoleums, a tiled tomb, a wooden building, six sandstone sarcophaguses, and at least 15 lead coffins. Some of the dead were interred with extremely high-quality objects, among them some of the rarest to be found in Roman Gaul. Although some graves almost certainly belonged to members of Augustodunum’s early Christian community, researchers have not been able to definitively establish the religious affiliations, or even the names, of any of the deceased—very few of the funerary containers are inscribed. Some are marked with “X”s, which Tisserand explains were used to indicate the position of the body inside—a single mark for the head and two for the feet—so that once the coffins were closed, the heads could be oriented to the west, as was customary. “This is simply a question of practical and not religious marks,” says Tisserand.

The necropolis’ earliest burials seem to date to between A.D. 200 and 250, and it was fully in use by the 270s. It eventually became the city’s main cemetery. “For the earliest graves there are no clear signs of Christianity, as the grave goods, mainly ceramics, also occur in ‘pagan’ graves,” says Kasprzyk. “The main question regarding these early graves is are they already Christian, since we know that Saint-Pierre is Augustodunum’s main Christian cemetery from the fourth to sixth centuries, or is this cemetery a ‘pagan’ cemetery in the third century and later ‘Christianized’?” Both Kasprzyk and Lavan raise the question of whether grave goods are reliable indicators of religious affiliation. “People at this time don’t show their identity through their jewelry or clothing,” Lavan says, “but there was a secular value system and a strong civic and secular culture of wearing social displays of rank.”

Nevertheless, the necropolis provides scholars with a wide-ranging opportunity to learn about the burial practices used in Augustodunum at the time. “The diversity of burial methods probably illustrates the diversity of the society in this period,” says Fossurier. “People whose status seems to have differed were interred side by side in the necropolis, and the variety of funerary containers and accompanying goods indicates that the cemetery was used for common people as well as the high-status rich or the very rich. We also know that men, women, and children were buried there.”

In the largest sarcophagus, which was deeply buried and sealed with iron spikes, the team found a gold hair ornament, a gold ring with a garnet, and a collection of pins made of amber. These pins, says Tisserand, are similar to examples made from other materials, but are the only known pins of this style carved from amber in the Roman world. Other burials contained pins and bracelets made of jet, a blue glass bead, coins, several glass and ceramic vessels, a child’s pair of gold earrings, and a copper-alloy belt buckle shaped like an amphora. The archaeologists also discovered dyed textile fragments, some of which were woven with gold threads. The pigment, characteristic of very wealthy burials of the period in the region, was extracted from the glands of murex snails from the Mediterranean.

A tremendous surprise awaited the team in a sarcophagus belonging to one of Augustodunum’s richest citizens. In it they discovered an example of one of the most luxurious artifacts from the Roman world—a type of late Roman glass vessel known as a cage cup, of which very few examples survive. These cups have intricate three-dimensional openwork designs in deep relief, usually geometric and much less frequently figural. “Cage cups are incredibly rare,” says ancient glass expert Carolyn Needell of the Chrysler Museum. “You almost never see them, and never in the ground.” In fact, the vessel found at Augustodunum is among the 10 best-preserved examples of Roman cage glass and the first complete vessel found in Gaul.

The cage cup from Augustodunum represents the pinnacle of Roman glassmaking. “What makes this cup extraordinary is the manufacturing technique,” says Tisserand. “It was probably carved from a single block of blown glass using techniques similar to those used by goldsmiths.” In fact, says Needell, cage cups are so difficult to make that scholars still debate how Roman glassmakers accomplished it. The Augustodunum cup must have been extraordinarily valuable. By way of comparison, says Tisserand, one of the last cage cups discovered was unearthed at the city of Taranes in what is now the Republic of North Macedonia in the 1970s. That cup was found along with a gold fibula, or clasp, inscribed with the name of the emperor Maximian (r. A.D. 286–305), an indication of its tremendous value. The inscription on the Augustodunum cage cup reads vivas feliciter, or “live happily.” The vessel is currently being restored at the Romano-Germanic Central Museum in Mainz, Germany.

Eumenius was born in Augustodunum to a family of educators—his grandfather came to Gaul from Athens and was a teacher of rhetoric. It is likely Eumenius attended the Maeniana, where he perfected the skills that led him to a career as Constantius’ private secretary, a position in which he was responsible for answering all petitions on the emperor’s behalf. In his A.D. 298 speech, Eumenius praised Constantius—no doubt to secure his patronage of Augustodunum and funds for its restoration. He pledged to donate half of the enormous salary of 60,000 sesterces the emperor had awarded him as the schools’ newly appointed head—twice what he had earned as his secretary—for the effort. This set in motion the restoration not only of his prestigious alma mater, but also of his hometown. Most of the burials discovered by the INRAP team date to after the late third-century siege, and the extraordinary grave goods likely provide evidence of the city’s recovery and its return to the thriving center of learned culture it had once been.