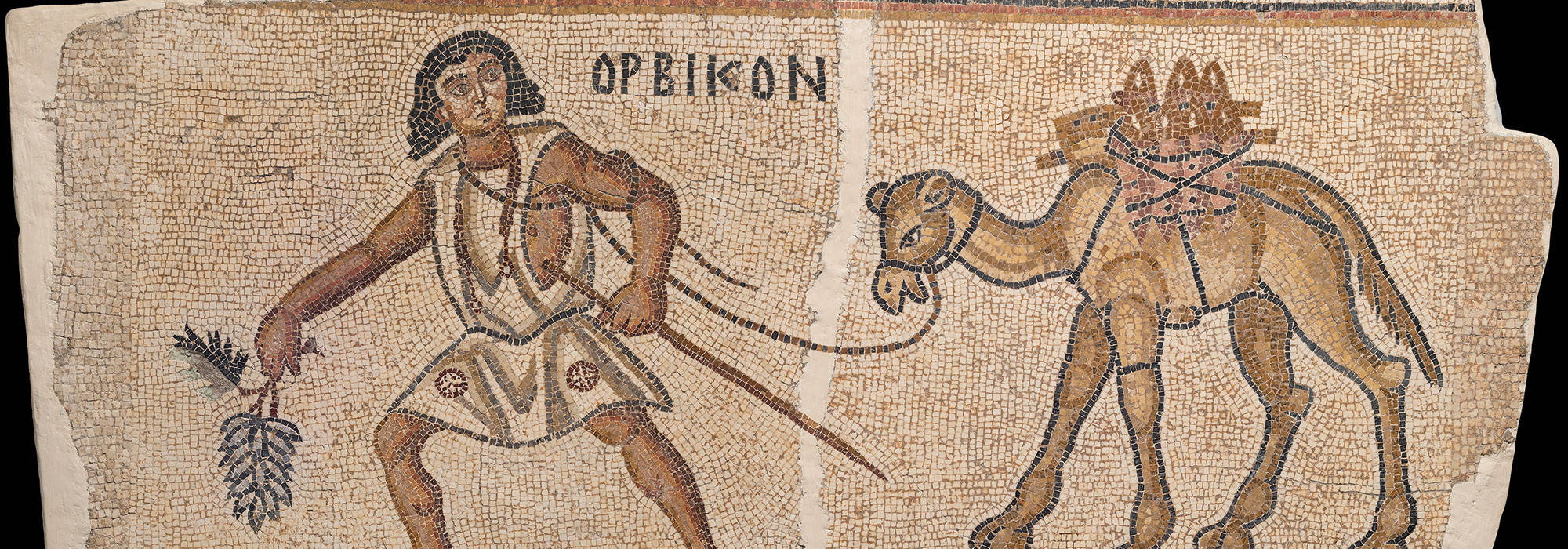

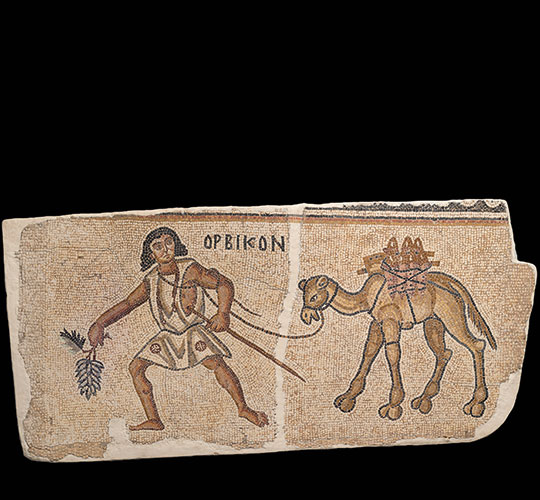

In the Byzantine era, vinum Gazetum, or Gaza wine, was shipped from the port of Gaza throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. “Gaza wine was considered a sweet, white luxury wine, praised by poets and mentioned in travelers’ accounts,” says archaeobotanist Daniel Fuks of Bar-Ilan University. The wine was packaged in ceramic “Gaza jars,” whose long, thin shape made them appropriate for transport via camel and boat. These jars have been recovered as far away as Britain, Germany, and Yemen, a testament to the spirit’s wide appeal.

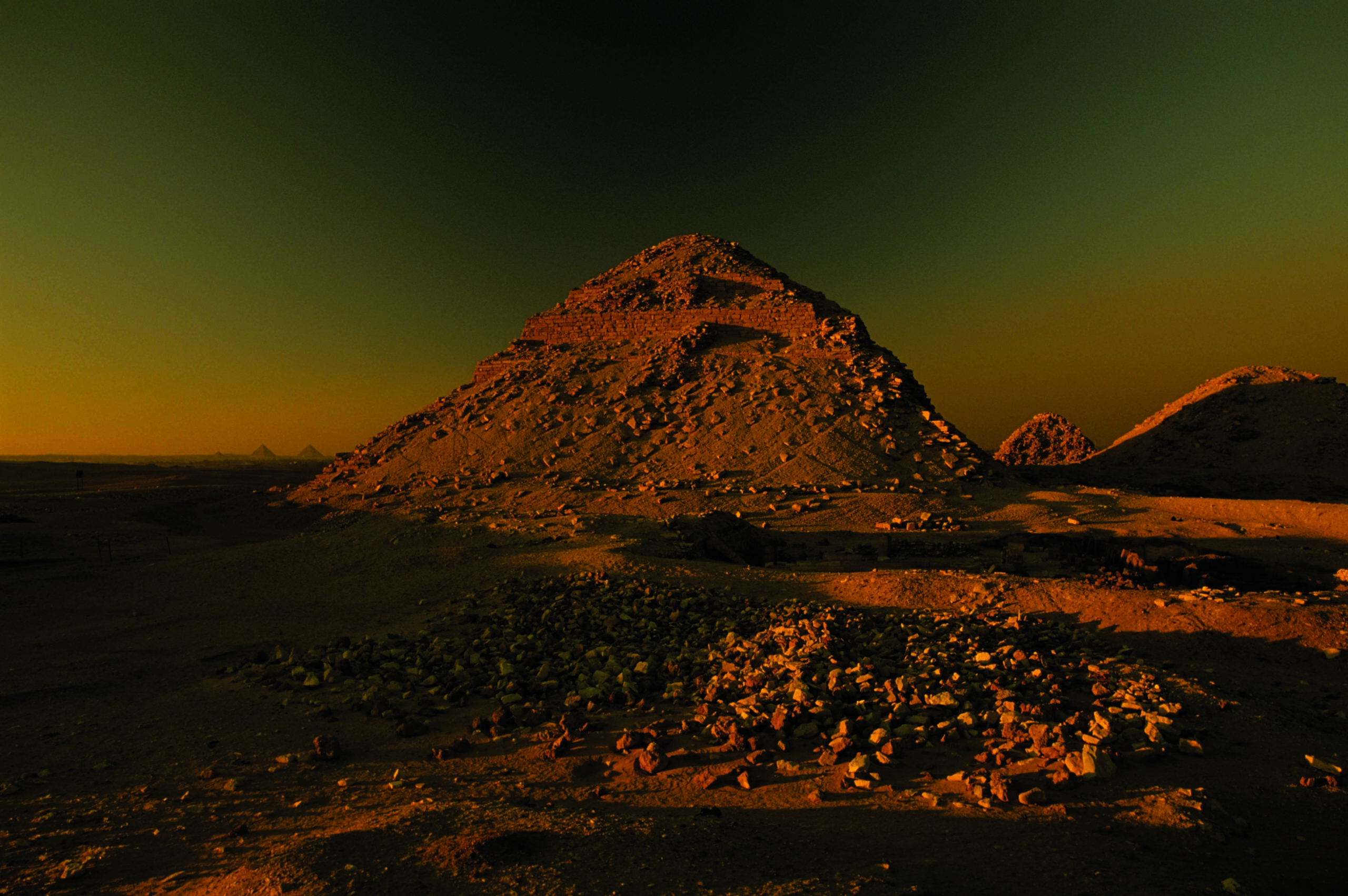

The Negev Highlands, some 30 to 60 miles inland from Gaza, has long been considered a likely site for Gaza wine production. Texts from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. describe vineyards there, and several large Byzantine winepresses have been discovered. Now, an archaeobotanical study led by Fuks provides clear evidence of the rise and fall of extensive grape growing in the Negev Highlands, as well as its apparent connection to the Gaza wine trade.

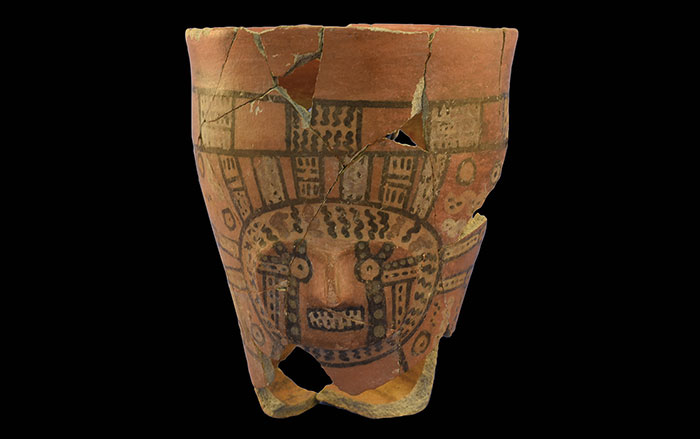

To track the intensity of local viticulture over time, Fuks and his team calculated the ratio of grape seeds to cereal grains from 11 trash mounds at three sites. They found the proportion of grape seeds rose from practically nothing in the third century to modest levels in the fourth to mid-fifth centuries. It peaked in the early sixth century before dropping sharply in the mid-sixth to mid-seventh centuries. The percentage of Gaza jars among the pottery in the trash mounds followed a strikingly similar trajectory. According to Fuks, this suggests that from roughly the fourth to sixth centuries, local farmers developed a commercial scale of viticulture connected to Mediterranean trade via Gaza.

Many scholars have linked the decline in the market for Gaza wine to the Islamic conquest of the region in the mid-seventh century. Fuks’ findings, however, indicate grape production in the Negev Highlands fell off a century earlier. Among the possible explanations, he says, are global cooling that may have led to unusually destructive flooding in the area and the outbreak of the Justinian plague in A.D. 541, which could have eroded demand for luxury goods throughout the region and reduced the supply of farmworkers.