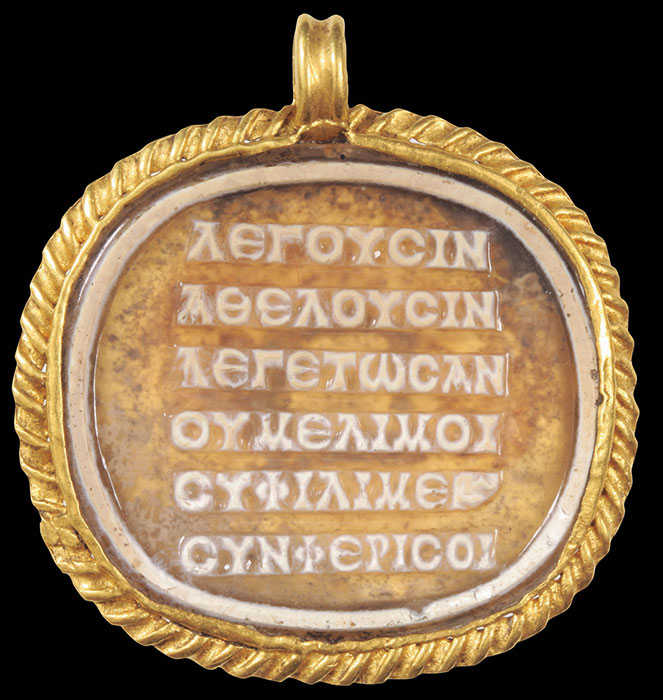

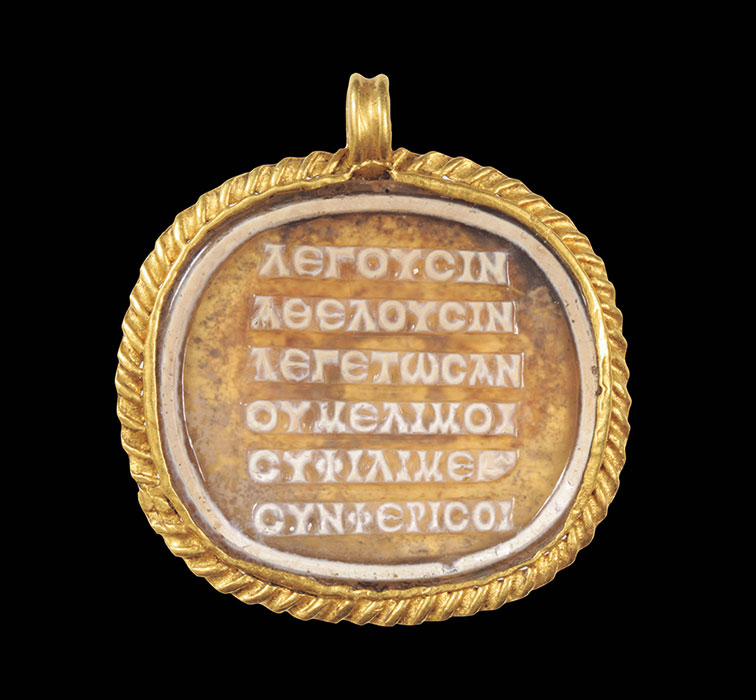

λέγουσιν They say

ἃ θέλουσιν What they like

λεγέτωσαν Let them say it

οὐ μέλι μοι I don’t care

σὺ φίλι με Go on, love me

συνφέρι σοι It does you good

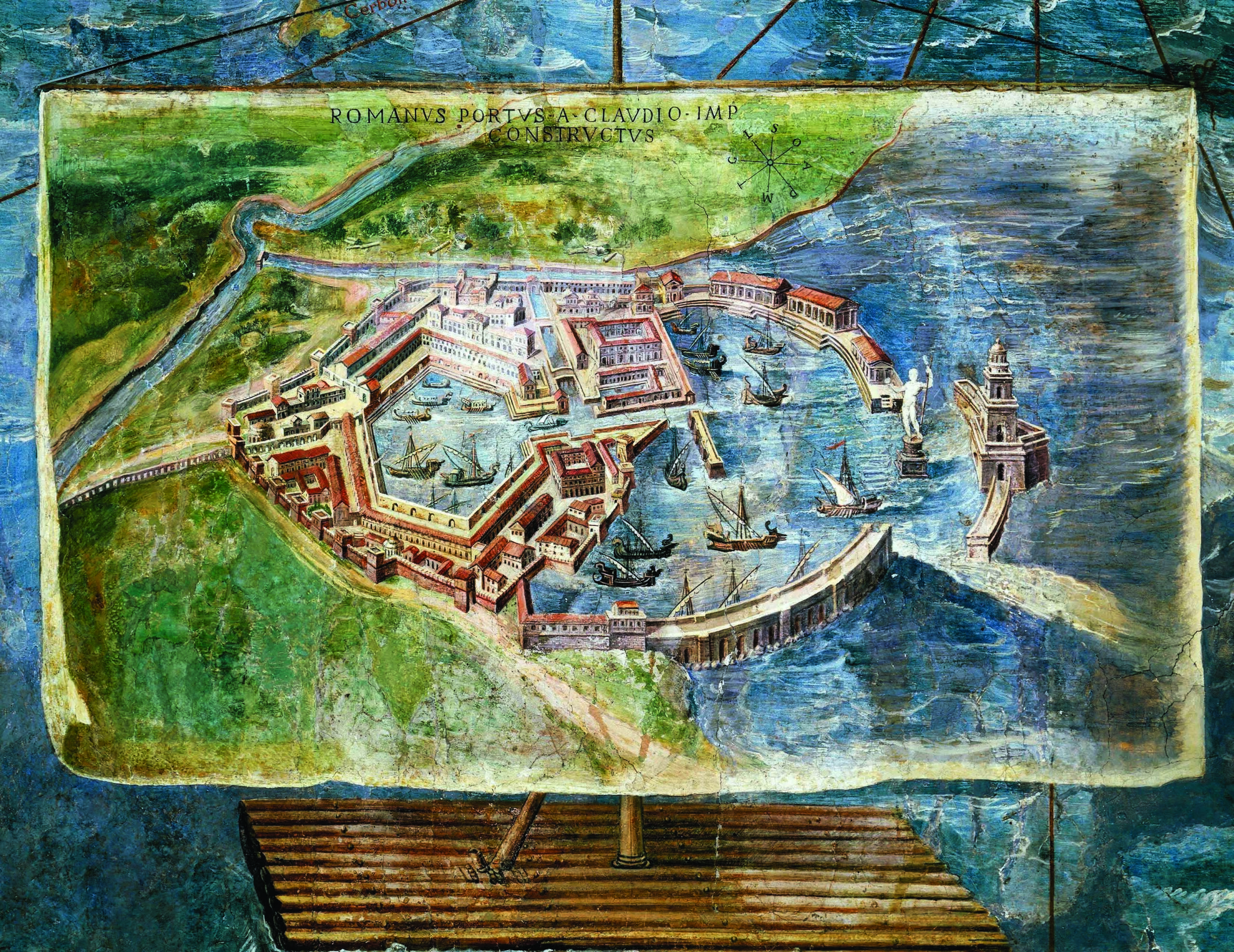

The past can be a silent place for archaeologists. Despite recovering the belongings of ancient people, analyzing their diets, and even studying their bones, scholars can only imagine how they might have sounded. One way philologists investigate how spoken words were pronounced in antiquity is by tracing changing spellings, especially in non-elite texts. “In popular texts, spelling is more likely to be adapted to the sound of the word and less likely to be tethered to some conservative idea of ‘proper’ spelling,” says classicist Tim Whitmarsh of the University of Cambridge. Another approach involves looking at surviving texts of all kinds, including poetry, to identify what they might reveal about how people spoke. Whitmarsh recently examined artifacts found across the Roman Empire, including 20 gemstones and a graffito on painted plaster in a house in Cartagena, Spain, all of which contain a popular short poem written in Greek. His conclusions may provide scarce direct evidence of a particular way that people spoke—one that persists in English and many other languages today—centuries earlier than previously known.

“Before the Middle Ages, many poetic traditions of the ‘classical’ cultures, such as Greek and Latin in what is now Europe, and Arabic and Persian further east, used a form of verse that was entirely different from anything we know of as poetry today,” Whitmarsh says. Up to that time, poems followed the rules of classical meter in which the meter, or rhythm, of a poem is determined by the length of time it takes to say the verse’s long and short syllables. “Think ‘hope’ versus ‘hop,’” says Whitmarsh. This regular pattern of short and long syllables is known as quantitative meter, and differs from the qualitative, or stressed, meter of the Middle Ages and beyond. As an example of the latter, try reciting “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” and note how some syllables are stressed—the “twin” in “twinkle,” “li” in “little,” and “star,”—or “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” where “Mar,” “ha,” “li,” and “lamb” are stressed.

Previously, scholars agreed that the earliest unambiguous examples of stressed poetry are works composed by the hymnist Romanos the Melodist in the mid-sixth century A.D. But Whitmarsh suggests that the inscribed poem he has been studying, which dates to the second or third century A.D., was recited in stressed meter. This would mean people in the Greek-speaking Roman Empire were accustomed to stressed speech centuries earlier than previously thought. “This way of speaking must have been bubbling around in the oral tradition,” says Whitmarsh. “Romanos wrote hymns using the stressed accent not to innovate spectacularly, but to plug in to the way normal people were speaking. This is a rare glimpse of how people actually sounded.”

Whitmarsh also believes the widely recited poem is evidence of an extraordinary crossover between popular culture and the written word in the form of a fashion statement. “From Spain to Iraq, everyone wants this little gemstone and its poem,” he says. The poem remained remarkably consistent through time and across the empire’s vast expanse, and seems to have appealed to a literate, but not especially high-status, sort of person. The gemstones are made of glass paste and the language is vernacular and includes no adjectives or nouns. “It’s about as simple as you can get,” says Whitmarsh. “It’s a kind of playground chat that starts in the middle of a conversation and has an easily reproducible rhythm that sounds like the main verse of Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode.’” There was also an economic dimension to the poem’s popularity and reach. “The Roman Empire produced wealth and opportunity that people had never had before and the chance to buy into culture and to travel and network in a way never before possible,” he says. “This object spread like wildfire because the empire was an information superhighway.”

To hear Whitmarsh recite the poem, click below: